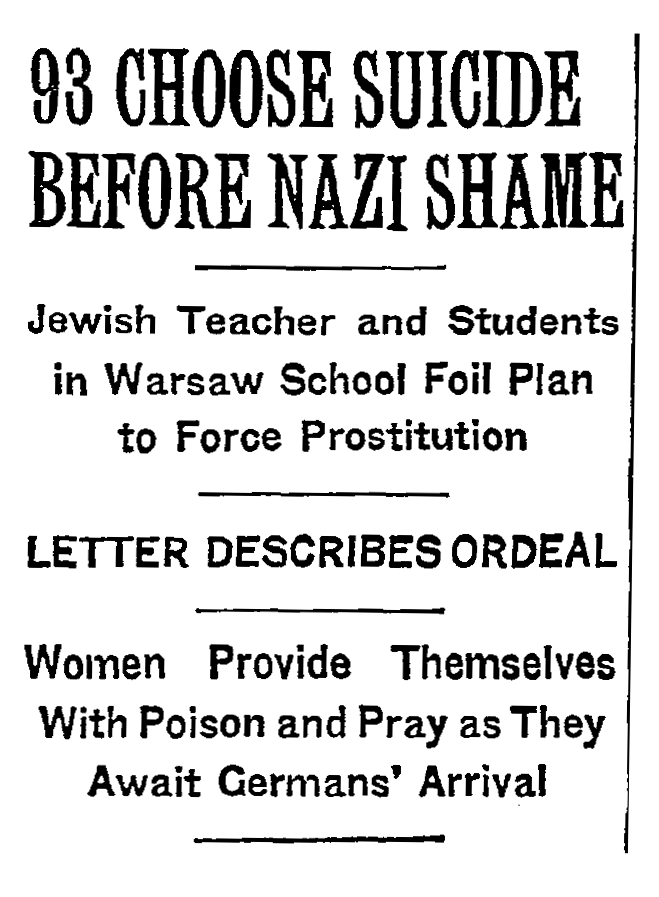

The story of the 93 Bais Yaakov girls from the Krakow Teachers’ Seminary, who killed themselves rather than be taken as prostitutes, appeared in the New York Times on January 8, 1943, about six months after the events described in the letter were supposed to have taken place. By February of 1943, news of this event reached the Land of Israel, where mass meetings were held, poetry was written, trees were planted, and streets were named in honor of the martyrs.

The story of the 93 Bais Yaakov girls from the Krakow Teachers’ Seminary, who killed themselves rather than be taken as prostitutes, appeared in the New York Times on January 8, 1943, about six months after the events described in the letter were supposed to have taken place. By February of 1943, news of this vent reached the Land of Israel, where mass meetings were held, poetry was written, trees were planted, and streets were named in honor of the martyrs.

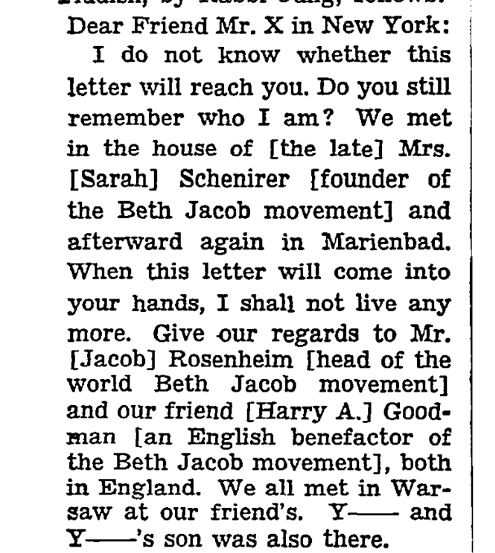

Beginning in the 1950s, a scholarly consensus has developed deeming this event a pious fiction. Mysteries nevertheless remain: Who wrote the first letter, purporting to be from Chaya Feldman, one of the 93 girls (this letter is sometimes called “The Last Will and Testament of the 93 Bais Yaakov Girls)? And who wrote the second one, by a purported eyewitness named Chana Weiss, which appeared in 1947 and lent dramatic detail to the events that had been missing in the brief first letter? Why would these letters have been written?

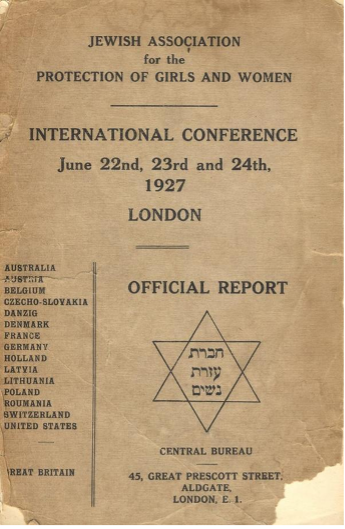

The fictional status of these events does not void their historical interest. On the contrary, the letters and the reactions they provoked are an important part of Bais Yaakov history, Orthodox Holocaust memory, and Jewish experience in the 1940s. Naomi Levenkron, for instance, has shed light on the group that sponsored the commemorations in Palestine, “The Committee for the Defense of the Honor of the Jewish Daughter.” This group arose not in response to the reports about the 93; it was already in existence, as a response to the scandals of the secular Zionist street, particularly Jewish prostitutes with Arab customers, and Jewish women who consorted with British colonial officials. For Bais Yaakov to ally itself with forces fighting Jewish prostitution was not a new phenomenon. In 1927, Leo Deutschlander, the chief administrator for Bais Yaakov in the Agudath Israel, attended a conference of organizers against the International White Slave Trade, the sex trafficking rings in which Jews were overrepresented as pimps and prostitutes; at the conference, he found valuable support for Bais Yaakov precisely as a bulwark against such travesties. In that respect, the Tel Aviv Committee was just continuing an old alliance.

In the weeks to come, we will present more documents about these events and their commemoration, in the original Hebrew or Yiddish and in English translation. In the meantime, we are presenting the commemorative booklet published in the summer of 1943, in honor of the 93—this publication was called for at the mass event described in the booklet.

As always, we are curious to hear from Bais Yaakov graduates and others about your responses to this story. Had you heard of the 93? Did this story figure in your education? What do you think it teaches us about Bais Yaakov?