The great scholar and historian Yosef Hayyim Yerushalmi once wrote:

History is the faith of fallen Jews.

But what of Jews who are not fallen? Have they no need for history? Might history be a danger to simple faith, insofar as simple faith rests on the notion that the ways things are now are as they have ever been? If the prohibition against publishing photos of women is a new stringency (which of course it is), the archives might provide us with evidence of that. And with many glorious photos of girls and women.

If Orthodoxy has sometimes been remiss in seriously engaging with its own history (where, for instance, was the English translation of Sarah Schenirer’s writings, all these years?), the secular and academic world have not exactly placed this history at the top of their agenda. The Orthodox press has barely begun to be digitized on such websites as JPRESS; the Yale Jewish Lives series passed on the opportunity to publish a biography of Sarah Schenirer (Sarah who?); and we still have only a few serious studies of, for instance, the Agudah.

There are, though, a lot more historians in the Orthodox world than you might think, including many passionate independent scholars, amateurs in the etymological sense of that term. I’ve met most of them only online, where a kind of fellowship of web surfers and auction-house treasure hunters thrives. But where a treasure hunter might be hoarding their gold, these new friends are eager to share what they have found.

That so far, the historians of Bais Yaakov are mostly men, and all—as far as I know—Orthodox, tells me something precious about what history might still occasionally mean in the Orthodox world, and how the story of girls’ Torah education might inspire men, as well. I owe these friends more than I can say (I also owe a few of them copies of my book—which I’m sending out this week!).

And then there is David Birnbaum, the uncrowned king of this secret fellowship of historians.

In the basement of a modest house in the Orthodox neighborhood of Toronto, David (a retired architect and city planner), with the help of his brother Eleazar (professor emeritus of Turkish literature and history at the University of Toronto), has assembled an astonishingly rich, beautifully organized archive of their family history. Which is to say, an archive of Jewish history in the twentieth century, since the Birnbaum family seems to have been everywhere in this history:

- Nathan Birnbaum, coiner of the term Zionism, convener of the 1908 Czernowitz Conference, philosopher, general secretary of Agudath Israel beginning in 1919;

- Solomon Birnbaum, professor of Yiddish at the University of Hamburg, the University College London scholar who authenticated and dated the Dead Sea Scrolls;

- Uriel Birnbaum, artist and illustrator;

- Menachem Birnbaum, artist and literary critic;

- Jacob Birnbaum, founder of the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry.

In a word, not your average family archive.

There was a lot to see, during the too few hours I spent in the archive, including a letter from Solomon thanking my parents for hosting Jacob at our house in Boro Park over a Jewish holiday when Jacob was touring the shuls, trying to rouse the interest of the frum world in the plight of Soviet Jewry. (My father, Hillel Seidman, who had been an Agudah activist in interwar Poland, was an admirer of Jacob Birnbaum and of the Birnbaum family, more generally. He also supported Jacob’s cause and helped introduce him to the Boro Park community in the 1960s.)

But I was mostly there to see what the archives had to say about Bais Yaakov.

Nathan Birnbaum became interested in Orthodoxy in 1911-12, and was fully observant by about 1916, bringing his family along with him into the Orthodox world (where they remain). Nathan was not content to be religious; he also wanted to transform Orthodoxy, to restore its sense of pride in tradition. He believed that observant Jews were losing their passion, along with their self-confidence in their religious choices.

It was with these ideas in mind that he founded a collectivist movement called “Olim” (the “Ascenders”), which he hoped would reinvigorate the religious world.

Nathan and Solomon (Shloyme) Birnbaum, the most famous baalei tshuva (“born-again” Orthodox Jews) affiliated with Agudah, were figures of fascination throughout interwar Orthodoxy. But nowhere was this truer than in Bais Yaakov.

Bais Yaakov itself was a kind of ba’al tshuva movement, bringing girls “back” to tradition rather than—as with their male counterparts—continuing the ways of generations past.

Bais Yaakov was also more open, in general, to German-Jewish influence, including teachers and administrators from German-speaking lands in ways that would have been unthinkable in Eastern European yeshivas.

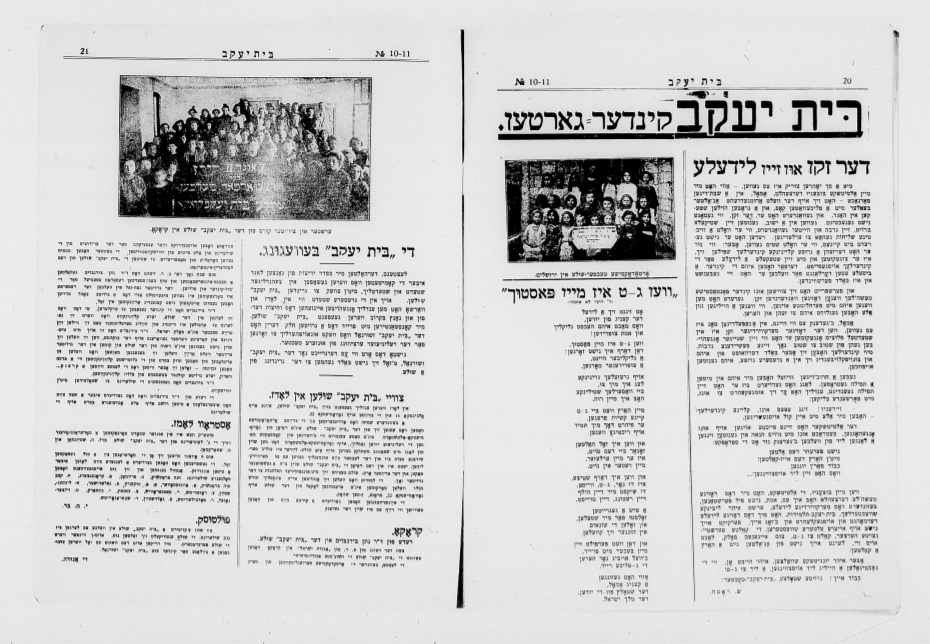

And as a new, revolutionary movement, it was open to the revolutionary influences propagated by the Birnbaums, including Shloyme’s attempt to standardize an Orthodox Yiddish orthography, pronunciation and style, in opposition to YIVO’s secular and Lithuanian-inflected standardization.

Bais Yaakov adopted not only his Yiddish textbook but also his Orthodox Yiddishism, calling in 1929 for girls to speak only Yiddish, in the traditional Polish pronunciation, and to take back their Jewish names.

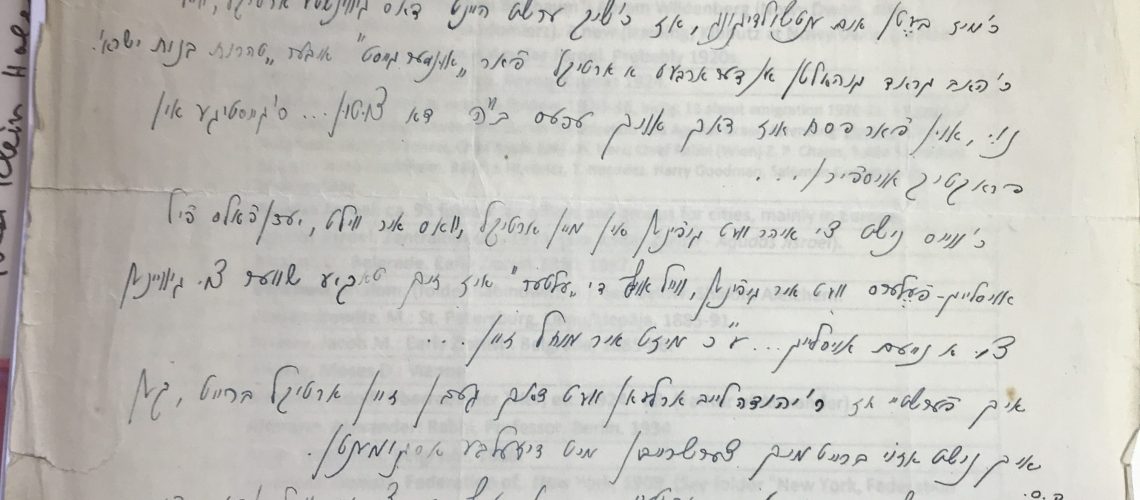

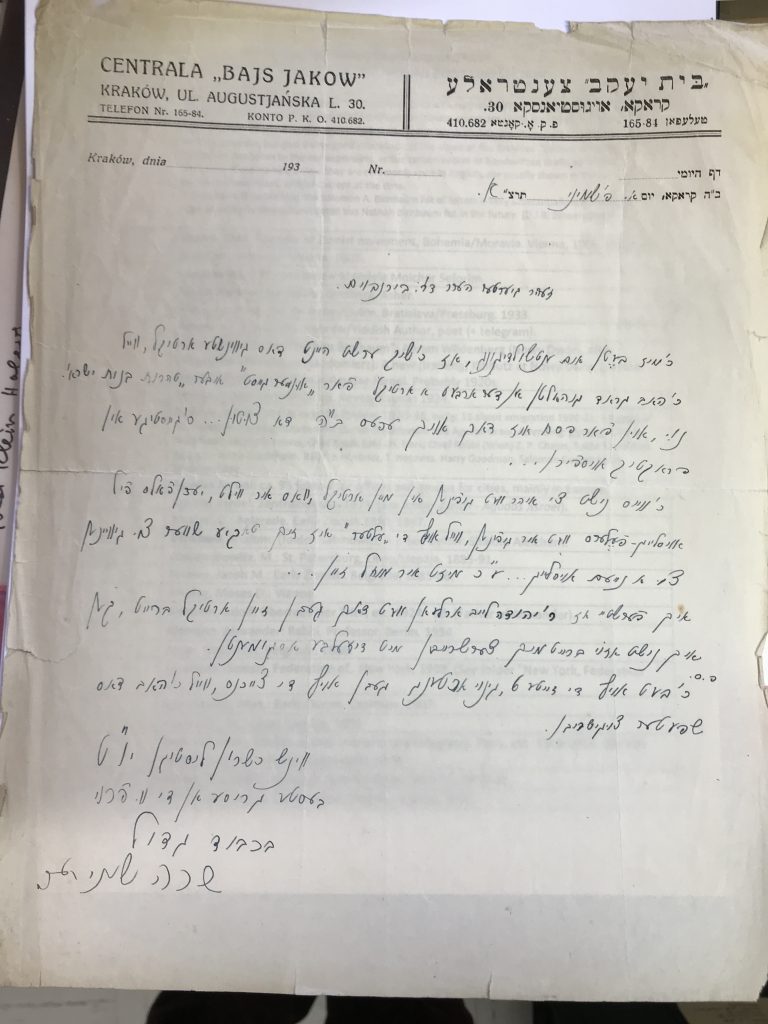

A letter from Sarah Schenirer to Shloyme Birnbaum (below) preserved in the archive describes, among other subjects, the difficulty of an older generation to accept and learn the rules of his new orthography, even if this orthography also presented itself as a return to older Yiddish traditions.

So, too, did Bais Yaakov appreciate the beautiful style of Uriel Birnbaum, commissioning him to design the cornerstone of the Kraków Seminary building and the document commemorating the cornerstone laying ceremony in September 1927. This stone and document are buried not in the archives but rather under the building, which still stands today.

But there are many other treasures in the Birnbaum family archive, which faithfully preserves aspects of Orthodox history for historians in generations to come.

Naomi Seidman is the Chancellor Jackman Professor of the Arts in the Department for the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto and a 2016 Guggenheim Fellow; her 2019 book, Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition, explores the history of the movement in the interwar period.