Among the most visible signs of the Orthodox move to the right over the past few decades has been the creep of separations between men and women, boys and girls, beyond the shul and school, to weddings, parks, buses, and now even sidewalks and airplane aisles.

The term “gender segregation” is deceptively neutral. The arrangement generally puts women in the back of the bus, requires them to follow strict modesty codes, reads them as potential sexual temptresses whose modesty or (even better) invisibility keeps men from sin. Their faces may not be seen, their voices may not be heard, by a man.

Their own spiritual expressions—for instance, singing a prayer or song out loud—hardly matter in this scheme, which concerns itself solely with the relationship between God and (the Jewish) man.

This was of course already the case in Eastern Europe, where Bais Yaakov arose within a community in which gender segregation had helped propel the crisis of young girls’ defections from Orthodoxy. Girls, excluded from the Hasidic court and the yeshiva, looked elsewhere for activities, experiences, relationships.

When Bais Yaakov sought to find opportunities for girls’ spiritual experiences, some on the right of the Orthodox spectrum objected less on the grounds of what was happening in these schools than on the effect this experiment might have on men. The Munkatcher Rebbe Chaim Elazar Spira was angered that the singing voices of Bais Yaakov girls, praying the Friday evening service together in their school, could be heard by boys and men in nearby prayer houses.

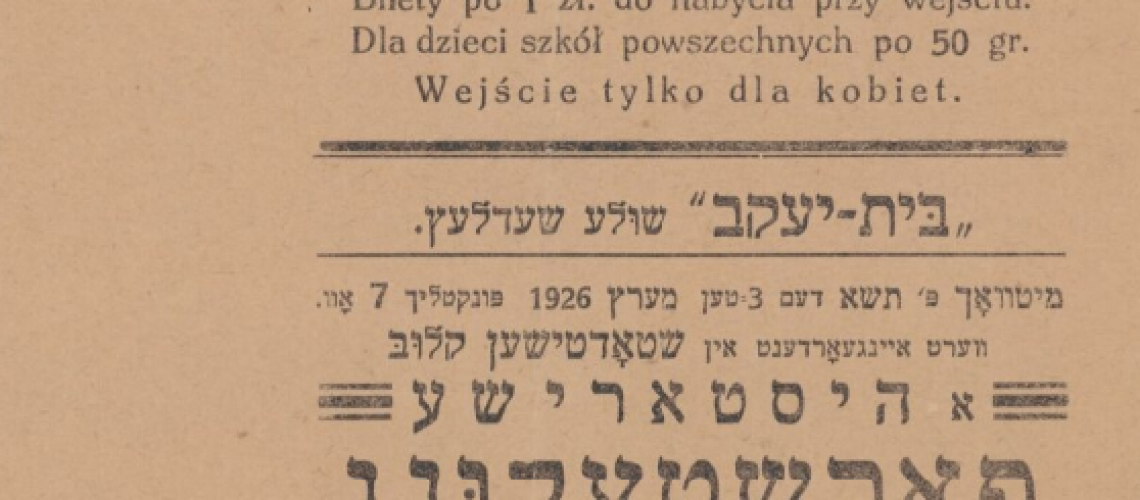

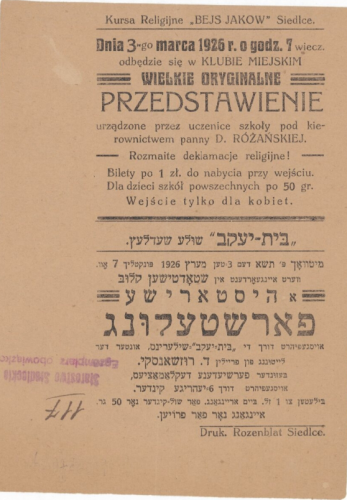

But what of the effect of gender segregation on women? That the increasing stringency is harmful to young girls is part of what Leslie Ginsparg Klein has been arguing, in multiple venues including the hashtag #frumwomenhavefaces and her rap/spoken word about how erasing women and girls harms the community. To peruse the website of a girls’ school and see nothing but photos of men, a familiar experience for those researching Bais Yaakov, sends a message that can hardly be entirely positive. (See my post about photos of girls and women in interwar Poland, where no similar taboo seems to have been in effect.)

But what if the effect is not entirely negative?

What if gender segregation was also an engine for spiritual energy and community cohesiveness for girls, as it seems to often be for boys and men?

Not that this was the point: it seems clear that the separation of women from men was not designed with women in mind, at all. Nevertheless, there are benefits, it seems to me, to growing up in a community of girls and women.

One of these might be a kind of disappearance of gender, or “femininity,” or the eyes of men within those all-girl classes and camps.

Despite the monitoring of skirt lengths and the expectation of being an “eydl meydl” or “kosher Jewish daughter” or “modest Jewish princess,” and despite the episodes in pizza stores and chat rooms, Orthodox girls grow up away from boys, in a world of girls and women.

Some of these girls grow up to direct films, in a time when female directors are still rare in Hollywood. Beyond these “kosher” films, directed to audiences of girls and women, the world of Bais Yaakov is rich with performance, music, dance—as rich as it has been nearly from the beginning.

These plays and performances had certain parallels among traditional Jewish male culture, but it seems to me that it was also a distinctly female phenomenon, with no real male counterpart. Denigrated by men as feminine and frivolous, this culture thrived with no men to witness it.

Might gender segregation provide the perfectly fertile ground for such cultural productivity? Along with the passion for gender segregation that has been driving so many Haredi communities, might we also be witnessing another sort of feminine passion within the world created by this segregation—a passion for performance, culture, and personal expression?

Naomi Seidman is the Chancellor Jackman Professor of the Arts in the Department for the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto and a 2016 Guggenheim Fellow; her 2019 book, Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition, explores the history of the movement in the interwar period.