Just in time for her eighty-seventh yahrzeit, Sarah Schenirer is recognized for what she was–a SUPERHERO!

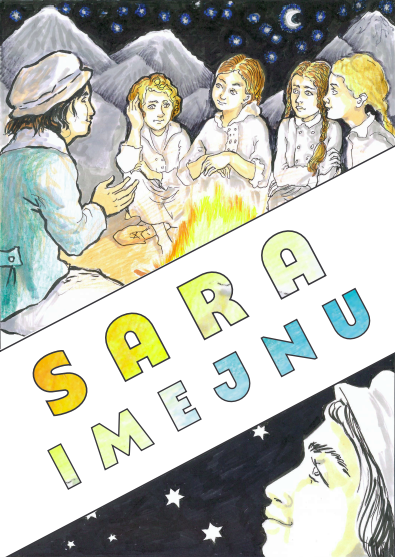

Krakow now has its very own Jewish, female comic book hero. Though her superpowers differ from Superman’s or Wonder Woman’s, her feats are no less astonishing and remarkable. Her will was stronger than steel, her vision powerful enough to change the course of history, and her convictions defied all odds. The graphic novel, Sara Imejnu, brings to life the revolutionary story of Sara Schenirer and her founding of the Bais Yaakov school system.

Sara Imejnu is a collaborative effort between a trio of young educators: Olga Adamowska, Justyna Arabska, and Marcjanna Kubala. In their respective roles at the Jewish Community Centre Krakow, the MIFGASH Foundation, and Hillel Krakow, they share a common mission of educating Polish students and youth about the rich Jewish culture of Krakow and Poland more generally. In a recent Zoom conversation, Olga, who describes herself as a Jewish feminist, explained that one of the motivations behind creating the graphic novel was the need to portray the Jewish culture and history of Poland before the Holocaust, to show young Poles that the Jewish community was full of colour and life. While there is only one surviving photo of Sara Schenirer, the graphic novel’s detailed illustrations and dynamic backgrounds indeed animate a lesser known side of Sara Schenirer, showing readers how she, Bais Yaakov, and her Orthodox community were more than the black-and-white photos found in textbooks or museums. “You get to see Sara Schenirer at different ages,” says Olga. By sharing and illustrating the story of Sara Schenirer and Bais Yaakov, the graphic novel also shines the spotlight on women leaders in Jewish history and how their important contributions to the community ensured its growth and survival.

Working in Krakow, the writers were constantly aware of how much Sara Schenirer was and continues to be part of the city. “Sara Schenirer is very much connected to Krakow, which is our city” explains Marcjanna, “the first Bais Yaakov school was in our neighborhood, where we go to work every day. I pass by this building every day on my way to work, so that is very inspiring.” The first Bais Yaakov teachers seminary was established on Świętego Stanisława Street right by the Vistula River, less than a ten minute walk from JCC Krakow. In the graphic novel, the Krakow scenes show a familiarity with the city’s landscape and its community, firmly situating Sara Schenirer and her revolutionary movement within her hometown. While the origin story of Bais Yaakov and its matriarch is well-known among the Orthodox community, the broader Krakovian and Polish public is largely unaware of their Polish roots. In showing the intimate connection between Sara Schenirer and Krakow, as well as Bais Yaakov’s growth in Łódź and Warsaw, the writers want the graphic novel to show how this revolution in women’s education is as much a part of Jewish history as it is Polish history, and vice versa. Having written the graphic novel in Polish, the writers hope they can bring Sara Schenirer into focus for the broader Polish community.

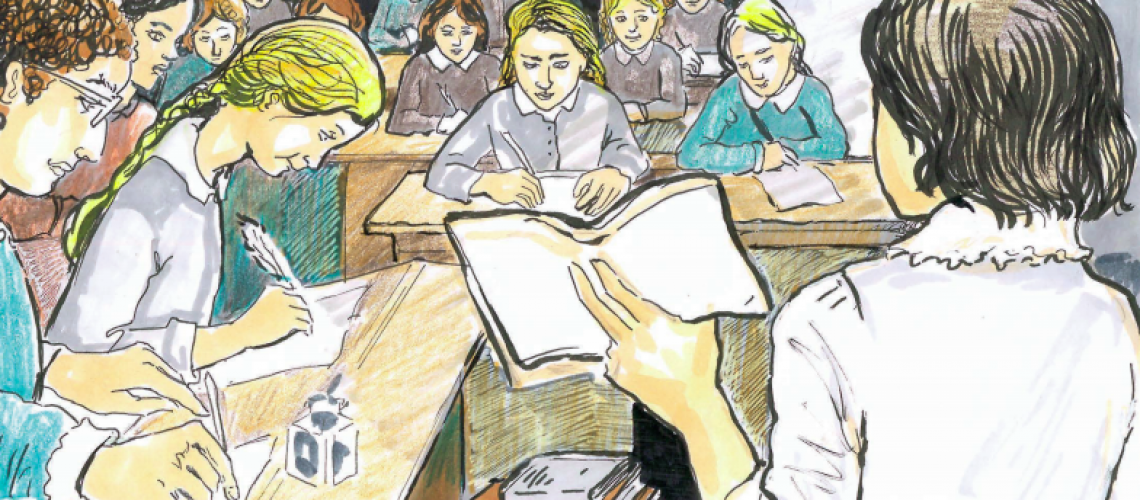

Sara Imejnu’s illustrations bring historical settings, histories, and characters to life. During the composition of the graphic novel, the writers knew it was crucial to find the right art and design to capture the exact places, communities, and customs of the era. More importantly, they had to find an artist that would capture the essence of Sara Schenirer and her vision of Bais Yaakov. After some searching, they came across the illustrations of Julia Naurzalijeva. Upon seeing her sketches, they all agreed, “This is Sara.” The soft, neutral colour palette effectively foregrounds the interpersonal dynamics between characters, which Naurzalijeva realizes with her organic line work. Whether the bustling streets of Krakow or the meditative Tatra mountains, the backgrounds animate the characters’ movement and dialogue. What is perhaps most striking in Naurzalijeva’s illustrations is the subtle detail of characters’ emotions. The singular facial expressions capture a deep range of emotion, reminding us of the human depth and intensity of the historical narrative: the dismissive glances in Sara Schenirer’s failed educational group for women; the fulfilling satisfaction that fills her first classroom; or the spiritual wonder and awe experienced in the Tatra mountains during an intimate observation of Lag BaOmer. Naurzalijeva’s illustrations truly bring the reader closer to Sara Schenirer.

With the composition and publication of Sara Imejnu, Adomowska, Arabska, Kubala, and Naurzalijeva are beginning a new chapter of cultural awareness and education. Sara Schenirer’s mission of education is not only expressed through the pages of the graphic novel, the text and images continue her work by educating younger generations about their history, culture, and community. An English translation is slated to be published before the summer, which will undoubtedly herald the graphic novel’s spread throughout North America. When asked about other translations, the writers wishfully pondered the possibility of Yiddish and Hebrew editions in the future. Currently at the JCC Krakow, there is an exhibition featuring the graphic novel which runs until the end of April; its illustrations, along with a few other original pieces by Naurzalijeva, are framed and displayed with additional commentary. The release of Sara Imejnu is both a testament to the significance of Sara Schenirer’s herstory and a living expression of her vision’s continuing impact. On Sara Schenirer’s 87th yahrzeit, her memory continues grow and her story is reaching more and more people.

Benjamin Bandosz is a PhD candidate and 2017 Vanier Scholar at the University of Toronto’s Centre for Comparative Literature. He has published on literature, media, and political economy in Deleuze and Guattari Studies, Journal of Urban Cultural Studies, and Journal of Canadian Studies. As a translator, Benjamin has worked with multimedia subtitling, academic articles, and archival documents. His critical translation work focuses on Polish-language news media’s translations in diasporic contexts, namely their expressions of nationalism and conservatism.