Combing through archives can be a tedious enterprise.

Take the Joint Distribution Committee Archive. It’s a beautiful and useful resource, not to mention freely available online. But some huge proportion of its holdings consist of pleas for money from desperate people, the JDC responses to these supplicants, and internal JDC memos about certain requests. From time to time, someone acknowledges the receipt of a check, or reports on a lost one.

The richest and most interesting material in the archives are the reports from people who received grants. Much of what we know about Bais Yaakov in the interwar period comes from these reports, although like all such reports, they have to be taken with a grain of salt.

Sometimes it is not the content of a letter or report that is striking, but something else about the document–a scribbled note in the margins, a surprising letterhead, etc. It was the stationery used for letters sent from London and Vienna that ended up sending me down an entirely unexpected avenue of research into Bais Yaakov.

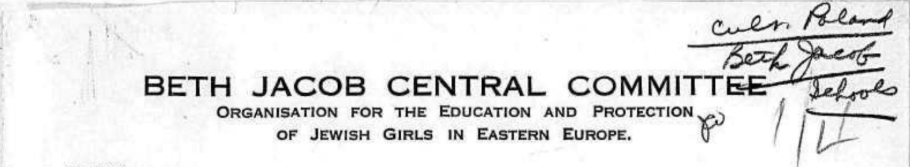

One such document was a 1937 letter from Jacob Rosenheim, in his capacity as President of the Bais Yaakov Central Committee in London (recently relocated from Vienna), acknowledging receipt of a check for $600 to be allotted to the Cracow Seminary and Ohel Soro in Lodz, the vocational training institute run by Eliezer Gershon Friedenson.

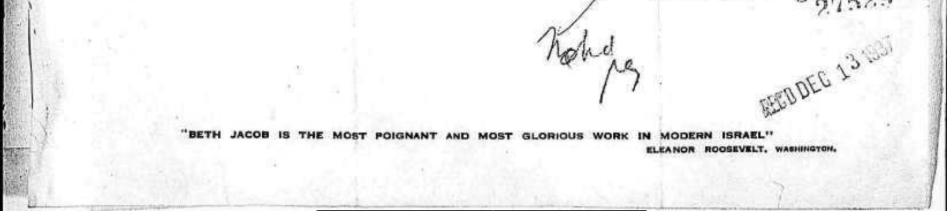

What first caught my eye was the endorsement at the bottom of the page, by Eleanor Roosevelt:

“Nothing I knew about the history of Bais Yaakov explained why Eleanor Roosevelt might have thought to praise the movement.

And why, for that matter, did the line of supporters and committee chairs on the left margin of the stationery include non-Orthodox Jews as Frieda Schiff Warburg (the wife of the banker Felix Warburg, and a member of the American Beth Jacob Committee)? Why would Edith Ayrton Zangwill (the wife of Israel Zangwill), a radical feminist and suffragist, have supported what was after all a traditional movement?

A clue to the appeal of Bais Yaakov in such circles appeared in the letterhead:

Organization for the Education and Protection of Jewish Girls in Eastern Europe

Education, sure. But what kind of “protection” did Bais Yaakov provide?

The term “protection” that was used in the letterhead for and descriptions of the Bais Yaakov in Vienna and London (but never, to my knowledge, in Poland), was a genteel reference, I soon realized, to the fight against “the International White-Slave Trade,” the (rather odd and surely due for retirement) term for the transnational sex-traffic networks in which Eastern European Jews were particularly visible participants.

Bais Yaakov entered this arena in 1927, when Dr. Leo Deutschländer met Bertha Pappenheim at a London conference organized by Jewish activists seeking to combat the problem. Pappenheim had long pointed to a lack of Jewish education as chief among the reasons that propelled some girls to abandon their Orthodox homes. It was these girls, she thought, who were particularly susceptible to the “seduction” that was often the first step to a life of sex work.

Bertha Pappenheim was a feminist, and a lifelong observant Jew. The same was true of Flora Sassoon, a wealthy London-based supporter of Bais Yaakov. These women believed in Torah education for women (Flora Sassoon was considered to possess an impressive store of Jewish knowledge), and no doubt saw Bais Yaakov as doing two worthy things: teaching girls Torah, and protecting them from prostitution.

But for others less invested in the spiritual lives of Orthodox girls, the fact that Bais Yaakov was an educational movement was secondary to the role it played in fighting against the sex traffic in Jewish women.

From its side, Bais Yaakov certainly had a motivation to frame its mission in the dramatic narrative of “protecting” rather than merely “educating” Jewish girls. The sex traffic was an international enterprise, and so too was the effort to combat it. It drew in a range of philanthropists and activists in the Jewish world and beyond, and it was this network that Bais Yaakov was able to tap into in its fundraising efforts. These philanthropists may have felt moved by the idea of giving Jewish girls an Orthodox education, but if they were not, other motives might be found for them to open their wallets, including (for Western Jews) the desire to keep shameful Jewish stories off the front page of newspapers.

The girls who attended the schools and seminaries might have been surprised to hear that Western philanthropists and suffragists were supporting their movement in order to keep them from becoming prostitutes. Of course, there was no place in the discourse of Bais Yaakov for allusion to their sexual vulnerability, even in veiled terms. But in New York salons hosted by Mrs. Felix Warburg or in the praise of Eleanor Roosevelt, the already decades-old discussions about how to stop the embarrassing spectacle of Jewish participation in the International White-Slave Trade, and the wonders of Beth Jacob, were two sides of a single fundraising coin.

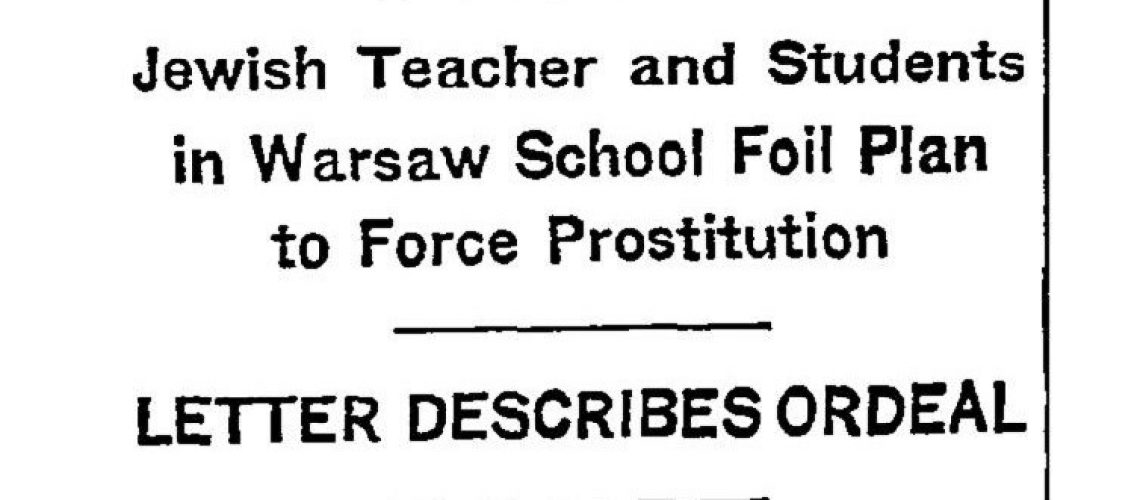

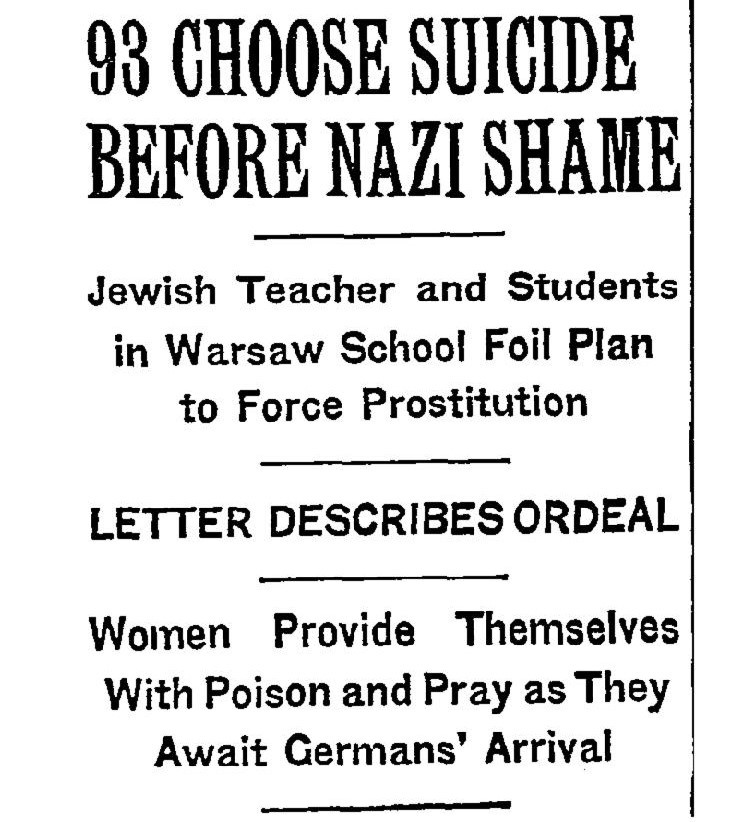

This curious aspect of Bais Yaakov history in its transnational reach might help explain another lingering mystery about the movement, the “Last Will of the 93 Bais Yaakov Girls,” who killed themselves rather than be taken as prostitutes by German soldiers.

A broad (but not universal) scholarly consensus has asserted that the “will” is a fiction. (See here, here, here, here, and here for some scholarly and popular coverage of the story as myth.) But that hardly settles all the questions raised by this episode. If it was a fiction, then who wrote it, and for what purpose?

I have no more idea who wrote it than anyone, but it was clearly someone with an inside view. The letter itself, perhaps not coincidentally, was addressed to Meir Schenkalewsky, an Agudah activist who moved from Hamburg to the United States in 1934 and lobbied the White House and State Department on behalf of Orthodox causes; it was Schenkalewsky who introduced the “most glorious work of Beth Jacob” to Eleanor Roosevelt.

Could the history of Bais Yaakov fundraising efforts through the well-established channels of anti-prostitution activism help explain the “Last Will and Testament”? Like the letterhead of the Vienna and London offices, this document, too, depicted Bais Yaakov girls as potential prostitutes, and much more explicitly —of course, in vastly more horrific circumstances than anyone in the 1920s and 1930s could have dreamed. This is not a fundraising appeal, and the letter names no committees or benefactors who might be able to step in and “protect” the girls.

But the poignant and glorious spirit of Bais Yaakov that Eleanor Roosevelt had praised is nevertheless at work in this letter, keeping them safe from forced prostitution even within the hell of the Holocaust.

Bais Yaakov, even without the help of London philanthropists, was performing the work it was created to do, and it was to the West that the poignant news of this small triumph was directed.