She loomed large, a touchstone on the way into the corridors of Bais Yaakov Academy. Her face radiated a time-worn charm, and the simplicity of her dress, nary a stitch reflective of modern sensibilities, was a subtle reminder of the foundational principles of Bais Yaakov. Not without color, not stripped of light, yet fiercely conservative, harking back to plainer times when devout mothers rocked their babies to sleep with a sacred lullaby.

It wasn’t only the picture of Sarah Schenirer that radiated nostalgic messages. Principal Felice Rochel Blau embodied Sarah’s aura as she greeted her students each morning. Morah Blau’s Sarah Schenirer reflected her own concept of what Bais Yaakov represented, and the portrait she created resembled a hazy cameo of a maternal figure with a high, almost clerical collar encircling her neck. The spirit of Sarah Schenirer was similarly evident in the song that Morah Blau wrote, part sacred lullaby and part ode to one whose “memory shall continue to live on forevermore”. This was a woman whose wisdom, whose dream, still lit a path for her spiritual descendants. How closely did the song about Sarah Schenirer and her portrait in the school hallway actually resemble the historical figure?

Sarah Schenirer’s resolute refusal to be photographed is a famous part of her legacy. Other women of her time, such as the Gerrer Rebbetzin, apparently did agree to have their photos printed in the pages of the Bais Yaakov Journal, which also printed the photos of many other girls and women. But the absence of a photo of Sarah Schenirer had a lasting effect on Bais Yaakov culture. The void, whatever it meant, could be taken to signify a subliminal lesson in modesty: A true Bais Yaakov girl does not post her picture on the printed page.

This absence did more than lend support to the later norms against publicly printing images of women. The lack of an image of the beloved Sarah Schenirer also gave free rein to those who would try to imagine her visage without having seen it for themselves. Who was Sarah Schenirer? What did she look like? What did she represent? With no physical manifestation available, women appropriated the drawing of her that circulated during her own life, and that was published in the 1933 Collected Writings. It was this drawing, more “feminine” than the photo that surfaced much later, with the dark wig and headkerchief and high lacy collar, that was the basis for others to use as they saw fit.

One of the most striking examples of the appropriation and reimagining of this drawing is evident in the publicity materials of the Israeli Haredi women’s organization, Nivcharot (the “chosen ones”). Their logo and masthead use a sharper graphic variation of the older drawing of Sarah Schenirer; the headkerchief and high collar are particularly recognizable. Oddly, the same image, accompanied by Sarah Schenirer’s signature, also appears on a short-sleeved, scoop-neck T-shirt available for purchase on the online shop.

The aims of Nivcharot include “empowering Haredi women and helping them to find their voice” and “expanding roles for Haredi women in public and private life,” as “the first and only Haredi feminist organization in Israel.” Sarah Schenirer plays a complex part in this equation, as a Haredi woman who had a visible public role as initiator of an institution that pushed the edges of traditional Haredi-Halakhic standards. But would she have been comfortable with the use of her image to promote this cause, or this T-shirt?

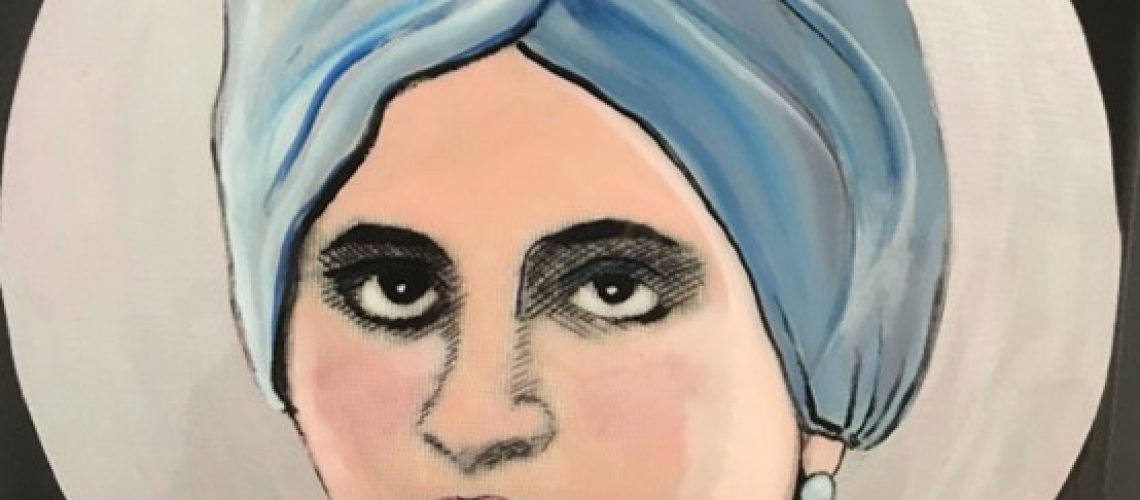

Representations of Sarah Schenirer have taken different forms in different communities and contexts. Joy Mahana, an artist rooted in the Syrian Jewish community of Brooklyn, is acclaimed for her unconventional portrayal of contemporary Rabbinic figures. In “The Rabbi Series”, Mahana reimagines rabbinic luminaries in vibrant color, freeing them from the sepia tones that characterize most portraits of the genre. Mahana has similarly reinvented Sarah Schenirer, again with her stand-up collar in place. But Mahana’s take is a glamour portrait, in tune with the heightened physical aesthetic that characterizes many Syrian Jewish women. Her features softened, her eyes fashionably yet hauntingly rimmed with kohl, and with a demure earring now visible below the bright blue kerchief, this Sarah Schenirer is more alluring than somber, an arbiter of educational messages that will resonate with women who aspire to both truth and beauty.

Another institution, this time a Lubavitcher girls high school in Brooklyn, creatively juxtaposed a redesigned image of Sarah Schenirer alongside two other Sarahs: Sarah Katzenelenbogen, a locally celebrated role model, as well as Sarah the Matriarch, wife of the forefather Abraham (imagining her, in somewhat Orientalist style, as a partially veiled but beautiful woman, faithful to the scriptural description of Sarah while adhering to Haredi models that discourage close depictions of Biblical figures). This image advertises a school performance that highlights the links that connect the three women. Chabad/Lubavitch does not traditionally associate itself with the Bais Yaakov tradition. Bearers of their own proud legacy of women’s education with its idiosyncratic Hasidic customs, Chabad sets its own standards. But Bais Yaakov Ohel Sarah is clearly an outlier. It is listed as a member school on Chabad.org, but the site omits “Bais Yaakov” from the school’s name; COLlive.com, another Lubavitcher online magazine, references it as B.Y. Ohel Sarah in its advertisements. However, in Flatbush, where the school is located, it is the Bais Yaakov affiliation that appeals, and its addition to the institution’s name likely broadens the prospective student pool beyond the Chabad community alone.

This might be why the school was inspired to claim Sarah Schenirer as part of its legacy. The “mother of Bais Yaakov” is not generally invoked in Chabad; outside of it, Sarah Schenirer is often compared to the biblical matriarch “Sarah Imenu.” In this image and performance, three Sarahs form the chain of tradition: The biblical matriarch, the “mother of Bais Yaakov,” and the Chabad heroine who was instrumental in rescuing the Lubavitcher Rebbetzin from war-torn Europe. The drawing positions Sarah Katzenelnbogen in line with both her biblical namesake and the most celebrated Orthodox woman in twentieth-century Jewish history. Here, Sarah Schenirer seems to be drawn to resemble Sarah Katzenelenbogen. Her kerchief calls to mind a Russian hat, and blends with the veil of the biblical Sarah. The colorful tapestry behind the women serves as both stage curtain and biblical tent, combining modesty and performance in one image. All three figures look defiant, with proud features, appearing as women equal to the tasks ahead of them. Strength and spiritual fortitude, qualities emphasized in the female ecosystem of Chabad, clearly come through in this rendering.

Sarah Schenirer transformed not only women’s religious education but also, less directly, the ways in which Orthodox women perceive themselves and their roles and obligations. Her image continues to serve multiple purposes, imparting messages about women’s authority and modesty, religiosity and power. Each expression may mean as much about those who project her image as it does about Sarah Schenirer herself. Without an available image, her “face” could be claimed and reinvented by individuals or groups whose aims were either closer to, or more dissonant from, her own.

On the other hand, it seems to me that Sarah Schenirer’s refusal to circulate her picture has helped to mold current Haredi sensibilities, transposing one woman’s decision into what has become the currently accepted standard of tznius (modesty) in the Haredi press. Although her particular hesitation might have been a matter of individual preference rather than religious scrupulousness, the effect of diminishing female presence was strengthened by her obscurity. While Nivcharot takes Sarah Schenirer’s image to support the agenda of amplifying women’s representation and voices in public affairs, the absence or reinvention of her likeness might bolster the norms that render women less visible in the public sphere. Where would Sarah Schenirer find herself within this conversation on women’s visibility and modesty? Should those who reimagine her image hold themselves accountable to Sarah Schenirer’s own aspirations?

And what of the original photograph of Sarah Schenirer? In the age of the internet, her likeness, with its attendant enigmatic messages, is just a click away. She wanted her face to be hidden, but those who seek to find her, by tracing her physical image or by limning her spiritual legacy, will ultimately prevail.

Do you have an image of Sarah Schenirer to share with The Bais Yaakov Project? Please write to us at www.thebaisyaakovproject@gmail.com