Among the sixty-two photos of Bais Yaakov assembled on this site, over half of these are class photos.

When we were deciding on photos for my book on Bais Yaakov, the publisher at Littman Library, Connie Webber, advised against including any of these. She hardly needed to explain why. Class photos are remarkably similar, following an instantly recognizable and fairly strict set of conventions. These photos may have been of interest to those who were in these classes, where they can jog memories about classmates and teachers. And those that were sent to donors and philanthropic organizations along with reports—we found many of the photos on the website in the archives of the Joint Distribution Committee—no doubt captured the reality of what their money had bought more vividly than budgetary reports. But what else can they tell us that would justify their inclusion in a book on Bais Yaakov history?

It seems to me that they do continue to speak to us, not only in their subtle differences, but also in their uniformity and conventionality. Of course, these two dimensions of Bais Yaakov, its conservative adherence to the rules and ideals of Orthodoxy and its revolutionary character as a new phenomenon within this traditionalist world, were precisely the features of Bais Yaakov on which I focused.

But first to the conventions of the class photo:

- The students stand or sit in rows, often dressed in school uniforms.

- Each face should be seen, but their similar ages and demeanors marks them as that singular “class,” rather than a group of individuals or the multigenerational assortment that is a family.

- Of course, their teacher or teachers often appear alongside them, an older woman seated at the center or off to the side.

- A row of children may sit cross-legged on the floor.

- Somewhere toward the bottom of the photo a rectangular sign, perhaps held by a child, will identify the class or the school.

This same arrangement governs the Bais Yaakov class photo from the earliest iterations we have until the ones Dainy Bernstein has provided for the 1990s. These conventions speak to a certain continuity of the Bais Yaakov experience—and more generally, of school experience—beyond the differences between black-and-white and color photography, interwar Poland and Bais Yaakov today.

And yet, within these similarities, the differences speak loudly, too.

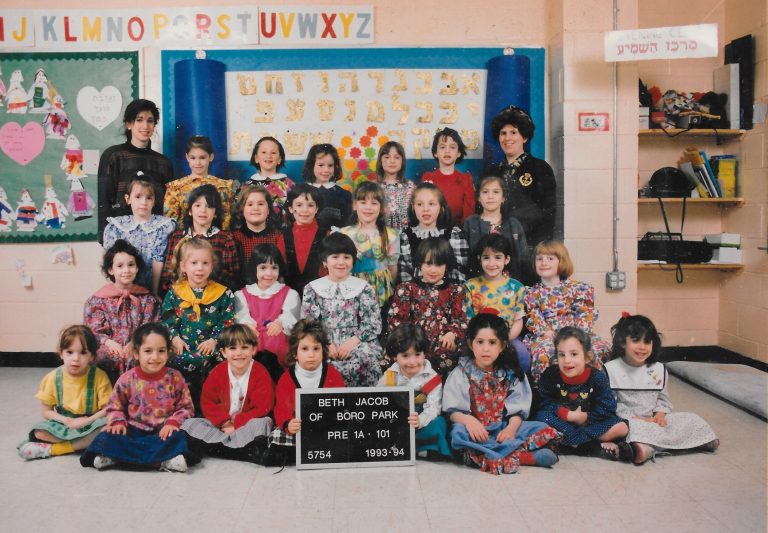

The above photo from 1993-94, for example, shows girls in the Pre-1-A class dressed colorfully for the photo, so colorfully that it might be imagined that the wild profusion of flowered dresses was somehow coordinated to produce such an effect. The photo’s setting is the classroom, with the English and Hebrew alphabets displayed on the walls behind them and “Merkaz HaShemiya” – a “listening corner” – visible on the right.

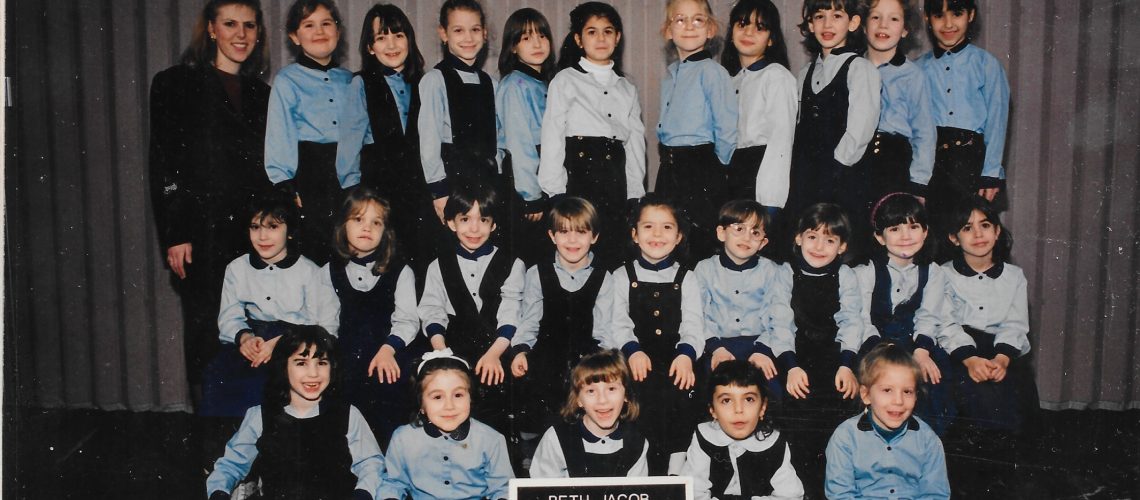

By contrast, in 1994-95, these same girls in their first grade class are already arrayed in uniforms. One of the girls in the back row is wearing a bright red flower in her hair, another is wearing a turtleneck under her shirt, and styles of skirt and jumpers differ – perhaps an attempt at distinction and individuality. The photo’s setting is the auditorium, where classes took turns arranging themselves for the photographer. The background is bare with no evidence of classroom activity.

How did these girls experience the transition from flowers to uniforms, sitting in their everyday environment versus a neutral auditorium?

And what about those long-ago class photos taken in interwar Bais Yaakov? On the one hand, many of them do conform to the rules of the class photo, so that we instantly understand them to be part of that recognizable genre. But they often push the limits of that genre in unexpected directions.

What to make, for instance, of the undated photo held by the Ghetto Fighters Archive of the Bais Yaakov in Grójec, which is labeled with the caption: “Pupils of the Bais Yaakov ultra-Orthodox girls’ school in Grójec, with their mothers and teachers.” Why the mothers? And what does it mean that it is so difficult to discern in this photo which are the young women and which their mothers? Many of these women are wearing stylish berets or cloches: does this category include daughters and mothers? Are any of these mothers wearing wigs? Were the mothers seated beside their daughters, or together, as if they formed a shadow class? Does this photo speak to a Bais Yaakov with a particularly active mothers’ association, or does it tell us something about the larger aim expressed by Sarah Schenirer of “bringing daughters back to the mothers, and mothers back to the daughters”? And what to make of those younger faces visible in the windows of what must be the school building?

The weeks that follow will be devoted to “reading” these school photos, which are easy to ignore as identical iterations of a too-familiar genre but nevertheless filled with the meanings of their specific concrete circumstances. The class photo, more generally, constitutes the frame for both individuality and the collective that never completely succeeds in subsuming the individuals that constitute it. As in the Bais Yaakov of Grójec, we cannot hope to discover all the answers to the questions raised by these photos, but the questions are worth asking anyway.

This blog post series was inspired by the recent publication by Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer, School Photos in Liquid Time: Reframing Difference. University of Washington Press, 2020.

Naomi Seidman is the Chancellor Jackman Professor of the Arts in the Department for the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto and a 2016 Guggenheim Fellow; her 2019 book, Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition, explores the history of the movement in the interwar period.