It might seem that the classroom photo is as simple, transparent, and conventional as a photograph can be. Its arrangement, with the students ideally all visible and facing forward, the teachers arrayed at the side, the board that acts as a caption for the class and school, is designed to convey straightforwardly its own identity.

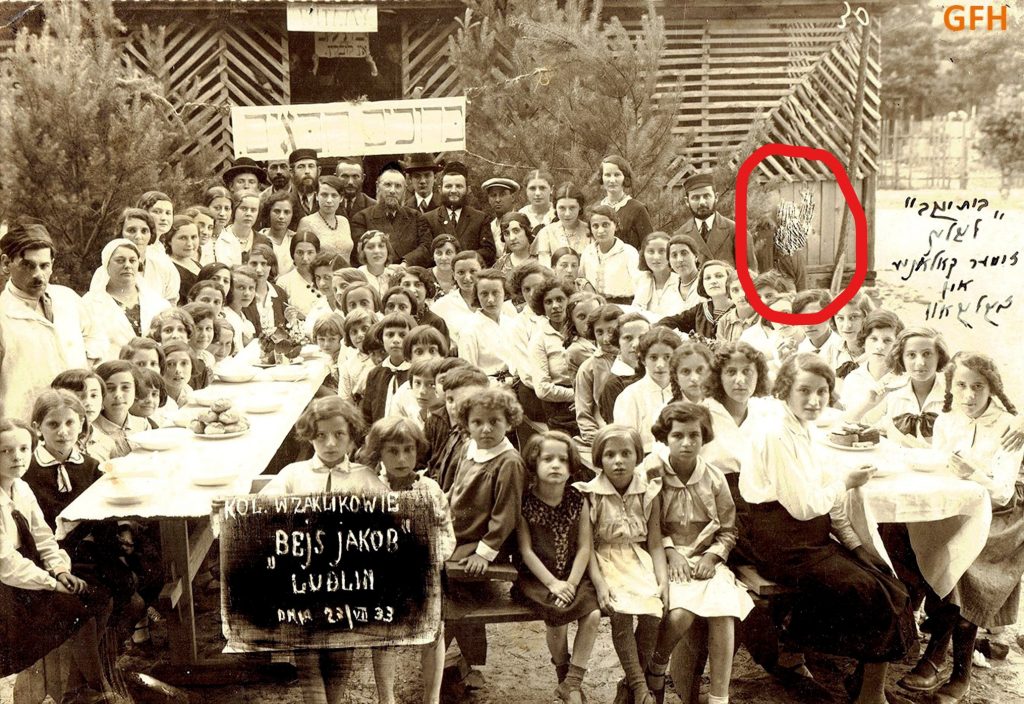

The photo the gifted Polish photographer Agnieszka Traczewska emailed to me this week conforms in some ways to this pattern. Although it depicts students outside, sitting at food-laden tables, its identity as a school photo is evident: the school—Bais Yaakov of Lublin—is signaled in three different ways:

- Behind the welcome sign (perhaps greeting a visiting delegation of men) children hold up a banner that reads “Bais Yaakov of Lublin”;

- at the bottom of the photo, another pair of girls holds up a board that specifies in black on white that the photo was taken at the Bais Yaakov of Lublin summer colony in Zaklików on July 23, 1933;

- a third handwritten note conveys the same information in a superimposed box at the right of the photo.

But the straightforward information conveyed in the board and banner and text box cannot resolve the mysteries posed by this photograph.

While we are fortunate to have the date on which the photo was taken, and even the name of the studio (Studio Victoria, in Lublin), the photo also has a history that transcends that single flash of the photographer’s camera: the photo has at least two trajectories, one to a newsroom in which the board appears in white on black, and another to an archive, in which it appears in black on white.

The text box at the right in the newspaper version is in Polish in the newspaper, and in Hebrew in the archival version of the photograph. The archive in which it appears is the Ghetto House Museum: apparently the photo was taken to Palestine in 1937, when a student who appears within it emigrated. While the newspaper photo is clearly a reproduction, it also may capture an earlier moment in the photo’s history, with the Polish rather than Hebrew handwritten description. Which, in such a case, is “the original,” which a copy?

The photo, taken in the open air, shows young girls seated at two tables, with a series of adults ranged around and behind them. Perhaps at least some of these adults are visiting for the day, as the Bruchim haba’aim banner implies. But who are they? Parents? Agudah activists? Administrators from the school in Lublin? Is that a nurse on the left, charged with the health of the children in an era with high rates of malnutrition, tuberculosis, and other diseases linked to urban poverty? Beside her stands a man who is clearly not part of the “rabbinical” group, but rather a worker in the camp—a cook or baker, perhaps, from his work uniform? We know that photos were sometimes appended to reports to the Joint Distribution Committee or other funding organizations, and these often showcase food bought with donated funds, or the healthful effects of the outdoors on city children. Does that explain the food piled before the children?

The photo has a companion that gives us a few more clues, but also raises new questions.

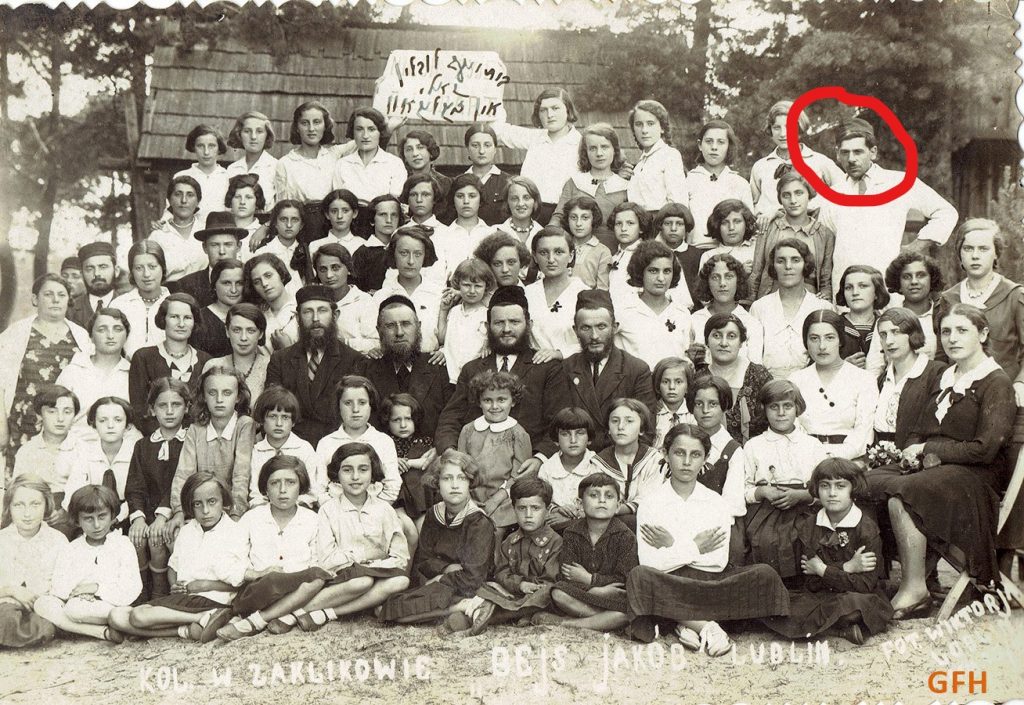

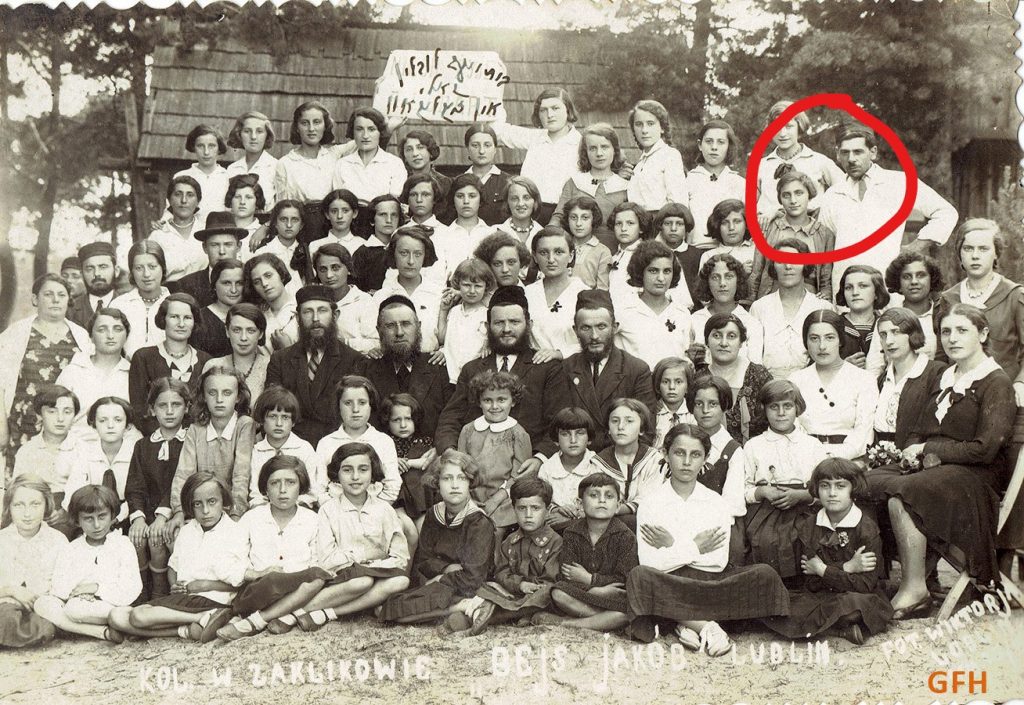

In this photo the group is arranged in an apparently more conventional pose, arrayed in rows against the side of a wooden building, with the youngest seated on the ground in front and all facing the photographer. Perhaps the photographer gave the girls instructions, because many in the front row hold their arms crossed before them in a similar pose. The mustached man at the left in the previous photo, so strikingly different in appearance from the other men, appears again, now at the right.

But the uniformity of the rows and the similarity of the poses are deceptive: Unlike the front row of young children, the rows above are messier, more diverse, and harder to categorize. Unlike the crossed arms in the front row, hands reach out to touch others in no clear pattern, two heads lean toward each other in companionship.

[The baker (or cook?) drapes a casual arm around the shoulders of a teenaged girl, who leans softly into him; in the other photo, she is seated with her group (seventh from the bottom on the right side of the right table). Are they related?] EDIT: As pointed out by Jewish Book Finds and Akiva Yasnyi on Twitter, the hand on the girl’s shoulder is a left hand, making it impossible to be the baker/cook’s hand.

A tangle of arms connects a group in the middle, of men and younger and older girls. A younger girl reaches back to hold hands with an older one. A man in the middle of the photo holds a smiling young girl between his knees, while an older girl rests her hands on his shoulders. Do these linked hands and easy touches represent family relationships within the relationships that govern schools or camps?

Fortunately, we have some information about at least three of the people in these photos, including the girl three down from the middle of the sign with her hands resting on the shoulders of the man seated in the row below her. As the Ghetto Fighters House Archive tells us, she is Bluma Cohen (later Hajdenkrug), and he is her uncle, Yaakov Mincberg; Bluma was raised by this uncle along with his wife Sara—after Sara died in 1934, her uncle raised her alone. Bluma’s cousin, Chana-Hinda Danziger, is seated third from the left in the first row of seated girls, in a shirt with three black buttons (she is also at the top of the left table in the other photo). Bluma moved to Palestine in 1937, when she was 17, and it may be her hand that wrote the Hebrew words appended to the table photo. The uncle who raised her, whose shoulders she rests her hands on, was killed in the Holocaust. But as with so many of these photographs, we do not know the fate of the others pictured.

Like the night sky, the photo yields other details with longer viewing. In the right background of the archival photo of the children at the table (this isn’t visible in the blurrier newspaper reproduction), there is a figure who seems to have been scratched out. A ghostly hand is raised above the scratch marks, as if signaling for our attention, like an interwar photobomber. Below the scratches is a pair of child-sized pants. Who is he (if he is a person, and not a garden gnome or figment of my imagination)? And who scratched out the image? Was he scratched out because as a boy he didn’t belong in this picture of Bais Yaakov schoolmates and their caretakers? Or do the scratch marks reveal and conceal a more personal animus? Was it Bluma who scratched it/him out?

A photo records a moment in time, and yet these photos record multiple moments in time. Not only that July day but also the date a few weeks later it appeared in a newspaper, the date it was packed into luggage for an overseas voyage, the date it was labeled and relabeled, the date it was scratched out, the date it was transferred to an heir, the date it ended up in an archive, and the date I received it from another Polish photographer, and the date it comes back—like a ghost—in this blog.

Each of these is a transformation, like the black-on-white or white-on-black naming of the school.

For those of us who have a scrapbook full of Bais Yaakov class photos, these photos that have escaped the general destruction of interwar Bais Yaakov are fascinating for their familiarity and for their differences. The casual touches among men and girls are among these differences, which hint at a different social order than the one I experienced in Boro Park.

But if they cannot fully capture the world of interwar Bais Yaakov, answer all our questions about what that was like, they can give us glimpses of this world, even—maybe especially—when they seek to obscure these experiences.

This post was updated on May 12, 2020, to reflect the correct information for the newspaper in which the photo appeared. Many thanks to Adam Kopciowski, who made the connection between the newspaper and the archived photo.

Naomi Seidman is the Chancellor Jackman Professor of the Arts in the Department for the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto and a 2016 Guggenheim Fellow; her 2019 book, Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition, explores the history of the movement in the interwar period. Naomi’s book was a finalist in the National Jewish Book Award’s Education and Jewish Identity category and a winner in the Women Studies category.