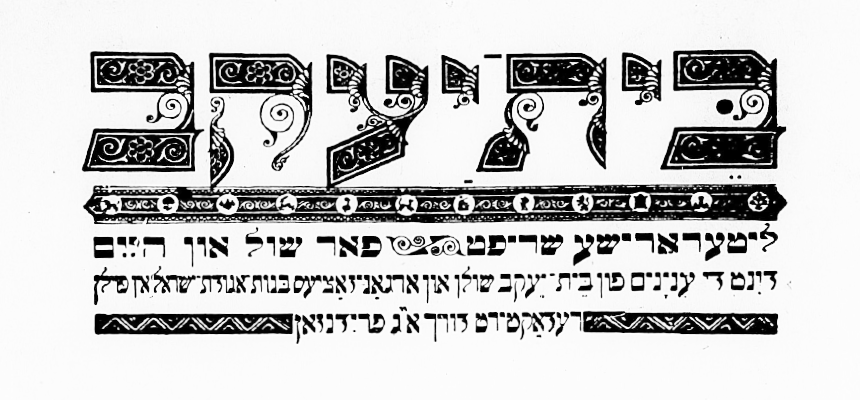

Among the goals of the Bais Yaakov Project was the digital upload and analysis of the official publication of the Bais Yaakov movement in Poland, the Bais Yaakov Journal. The journal, edited by Eliezer Gershon Friedenson, was launched even before the World Agudath Israel voted to support Bais Yaakov at its 1923 Congress. It was Friedenson’s own initiative: As a young activist in the Agudah, he would travel around Poland recruiting for the movement. As he remembers, he could parry any challenge thrown at him by the youth affiliated with Socialism or Zionism, until they asked him a question: “Tell us, where are your girls and women? You know where they are, in our clubs.” Cut to the quick, Friedenson took comfort from rumors about Sarah Schenirer’s initiatives. Traveling to Krakow, he asked her how he could help. It was Schenirer who suggested his publishing a newspaper that could spread the Bais Yaakov message across Poland, and within a few weeks, Friedenson had launched the inaugural issue. The journal, which published its last issue in 1939, would go on to become the women’s publication with the highest circulation and longest run in interwar Poland.

The journal, which sometimes was a monthly and sometimes biweekly, was more than just an attempt to unite a school system through the eminently modern means of the press. It also aimed to provide Orthodox girls and women with entertaining, inspiring, and kosher reading material. This purview was remarkably capacious—a series by Shmuel Nadler, for instance, introduced readers to Egyptian, Japanese, and Indian literature (Nadler, interestingly, abandoned Orthodox Judaism in 1934, when he became a Communist). The journal provided a much-appreciated outlet for Orthodox writers, including my father, whose first publication appeared in its page—a Polish poem written when he was just fourteen. The journal also tackled the question of what it meant to be a modern Orthodox woman, dealing with the challenges of the feminist discourse of the day. While the editorial board was apparently exclusively male, the editors actively encouraged women to submit their work, and regularly published their poetry and fiction. Sarah Schenirer, of course, was a regular contributor, appearing in almost every issue. The journal also provided its readers with a view into the larger political world, registering the rise of antisemitism as a threat that grew more ominous in the 1930s, and reporting on Orthodox life in Mandatory Palestine, Western and Central Europe, and the United States. Other Bais Yaakov publications followed, including an Israeli and American version of the paper that picked up after the Holocaust. But these were more modest and insular affairs, with little of the pioneering experimentation for which we have Friedenson to thank. Friedenson did not survive the Holocaust (Yosef Friedenson, his son, did, and carried on his father’s work in the Orthodox press). Our digitization efforts thus constitute a memorial to a gifted and dedicated activist and editor whose name is not often remembered.

Along with providing all available issues of the journal, the website also shows a summary of the contents of each issue. A few particularly interesting essays are also the subject of individual blogs, for those who cannot read Yiddish. As for what the journal can teach us, it is just beginning to yield its treasures for those with an interest in Bais Yaakov history, Orthodox literature, and interwar Polish culture.

View archive of the Bais Yaakov Journal »

The work of uploading and summarizing the journals began with Dainy Bernstein and continued with Miriam Schwartz. The Bais Yaakov Project is grateful for their contributions.