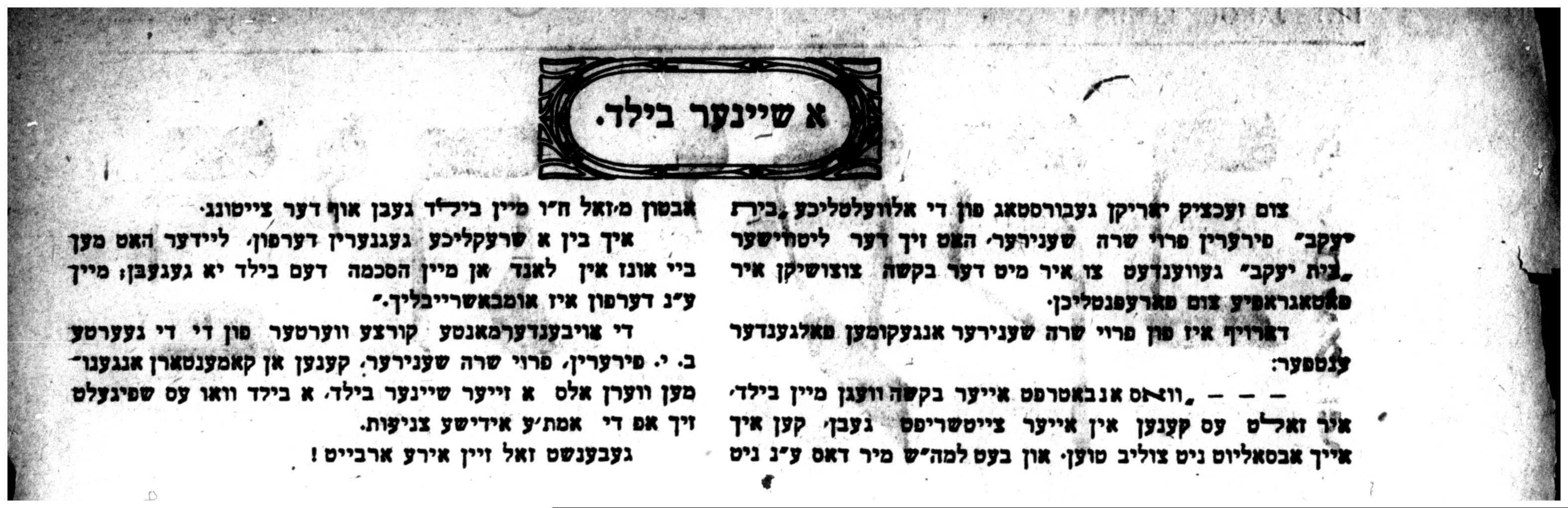

It’s well known to every Bais Yaakov girl that Sarah Schenirer did not want her photograph published. When I began my research almost ten years ago, there was still no widely available photo of her. Instead, what circulated was a line drawing that had been distributed by Bais Yaakov in the interwar period, and was included in the frontispiece of her 1933 Gizamelte shriftn (Collected Writings).

It was only in 2007 that the now-familiar photo (below) was published in SŚwiat przed katastrofą. Żydzi krakowscy w dwudziestoleciu międzywojennym (A World Before a Catastrophe: Krakow’s Jews Between the Wars), edited by Jan M. Malecki. The photo surfaced online in 2008 in a blog post on the Seforim Blog by Dr. Shnayer Leiman of YU.

The title of Pearl Benisch’s biography of Schenirer, Carry Me in Your Heart, refers to what Schenirer would say when asked for a photo from one of her beloved students: her resistance to being photographed was softened by her words, which made palpable the love and closeness that tied founder to followers, even in the absence of a photo.

Sarah Schenirer’s resistance to being photographed is of a piece with other aspects of how she is described in the movement, including her “shunning the spotlight” at the grand ceremony in 1927 to lay the cornerstone of the Krakow Seminary.

Her piety and modesty are sufficient to explain the absence of a photo of a woman so revered, whose photo would be cherished by thousands.

That many Orthodox publications, and even Bais Yaakov websites, now refrain from publishing photos of women and girls, lends support to the supposition that Schenirer held back her photo because of her commitment to feminine modesty.

That may well be true. But there are a number of other aspects of Sarah Schenirer’s biography that complicate this picture.

The presence of dozens of photos of women on this website, and in interwar Bais Yaakov publications, stands as evidence that Bais Yaakov had no conception of the publication of women’s photographs as immodest.

Many photographs were professionally done, and photography was clearly an important part of Bais Yaakov culture.

Moreover, the notion that Sarah Schenirer “shunned the spotlight” at the 1927 ceremony is qualified by contemporary newspaper reports, which simply describe the event as sexually segregated in the audience, with only men on the dais. This, too, was simply normal Agudah practice for public events. It makes sense to describe Sarah Schenirer as modestly refusing an invitation to sit on the dais only if such an invitation had been offered. But there is no reason to think it was.

The question might be more easily resolved by reading Sarah Schenirer’s own words in relation to a request for a photograph. I have found only one such direct quote, in a 1933 article in the Bais Yaakov Ruf, the periodical that served the Lithuanian branch of the movement. The anonymous article quotes a letter from Sarah Schenirer responding to the newspaper’s request:

In regard to your request for a photo to publish in your newspaper, I absolutely cannot do that for you, and further insist that my photograph will not, God forbid, appear in your newspaper. I am terribly against that, but unfortunately my photo has been published throughout the land without my consent, and my anguish over that has been indescribable.

Sarah Schenirer

The report continues by noting that these words can themselves provide a truly beautiful portrait of Frau Schenirer, a portrait that reflects her truly Jewish modesty.

This report seems to confirm the understanding of Sarah Schenirer’s reluctance to have her photo published as a form of Jewish piety, or at least shows us that this reluctance was understood in this way during her own lifetime. But the words, an apparent direct quotation from Frau Schenirer, do not spell out the reasons for her determination to keep her photo from publication.

Moreover, they express something of her strong will—she speaks of her rights, of consent, and makes her absolute refusal clear without attempting to soften her words.

Not modesty but rather fierce determination and self-protection are what come through in these words.

Might there have been another explanation?

Sarah Schenirer’s diary speaks of her sense of herself as unattractive, and records her pain (during her difficult first marriage) at feeling that she could hardly expect her husband’s love, given her lack of beauty. In this context, it may be relevant that the article that records her refusal to have her photo published also gets her age wrong: the article begins by stating that the newspaper sought the photograph in the context of celebrating her sixtieth birthday—in fact, Schenirer turned not sixty but fifty in July 1933.

Are we getting the picture straight, in subsuming all these complicated social and psychological factors under the rubric of “modesty”?

We now have a photo of Sarah Schenirer, one she would have fought to keep away from prying eyes. What are the ethics of showing it?

My own discomfort around these questions have led me to include the photo only in the context of the application form in which it appears, and as small as possible—admittedly a partial salve.

The face that appears on the form is less “feminine,” and more “modern” in some hard-to-describe fashion than the drawing.

Does it tell us something about Sarah Schenirer that the drawing did not?

Does the drawing tell us something about how Sarah Schenirer was idealized, and obscured, by the movement she founded?

Does some truth lie between the drawing and the photo?

What emerges from these photos and words, once we allow them to expand beyond the simple and comforting idea of Schenirer’s as the perfect image of a Jewish woman’s tsnies?

A previous version of this post mis-identified the first date of appearance of Sarah Schenirer’s photo.

Many thanks to Fred MacDowell for pointing out our error.

Naomi Seidman is the Chancellor Jackman Professor of the Arts in the Department for the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto and a 2016 Guggenheim Fellow; her 2019 book, Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition, explores the history of the movement in the interwar period.

![UM2018.021 (1) Sarah Schenirer's application for an identification card [National Archives Kraków, call number:

STGKR 990].](https://thebaisyaakovproject.religion.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/UM2018.021-1-owhkcauo9ekc8h38tythdyxhj6fzuk0r1g4q97fvk8.jpg)