Who would have predicted, even a few decades ago, that the Talmud would come to acquire what passes for glamour in the academic world?

I witnessed this as a doctoral student at the University of California, Berkeley, in the 1990s, where the internationally renowned Talmud scholar Daniel Boyarin was training a new cohort of young scholars.

There were also places like Drisha, or Svara, where serious Talmud study was available to people beyond the usual yeshiva demographic.

There were also places like Drisha, or Svara, where serious Talmud study was available to people beyond the usual yeshiva demographic.

But for all the excitement I saw in others falling in love with the Talmud, I somehow never caught the bug, despite participating in my share of partner study sessions and appreciating the rabbinics scholarship I read or heard.

Recently, it occurred to me that my failure to fall in love with the Talmud may have something to do with having been raised in the world of Bais Yaakov.

As a Bais Yaakov girl, I was of course excluded from study of the Talmud. The distinction between the permitted study of the Written Torah (the Bible and its commentaries) and the forbidden study of the Oral Torah (prototypically, the Talmud) is fundamental to the Bais Yaakov curriculum. It was this distinction that rendered organized Torah study by girls permissible in the eyes of rabbinical authorities of the time, who read Rabbi Eliezer’s famous dictum, “Anyone who teaches his daughter Torah teaches her tiflut (licentiousness, triviality),” as pertaining only to the study of rabbinic sources.

But all of this rationale was in the historical background of Bais Yaakov rather than part of the day-to-day culture of the school. In the Bais Yaakov schools in which I was raised, Torah was simply understood differently than it was for our brothers: we studied Torah in a way that kept us within the lines drawn by Rabbi Eliezer and his later interpreters, but without reference to those lines.

In short, we carried on a Jewish intellectual life as if we lacked for nothing, as if Rabbi Eliezer and his entire crowd had never existed – it was only in seminary, I think, that I was first introduced to that particular halakhic discussion.

In my last year as a Ph.D. student at UC Berkeley, Daniel Boyarin gave a job talk in which he argued for the legitimacy of women studying Talmud.

The question I put to him at the end of the talk was why women should want to study the Talmud.

He was clearly taken aback, as if the value of such study was so obvious to him that he had never considered that anyone might feel differently. But I did and do.

Of course, I have studied and taught rabbinic sources, and my book on Bais Yaakov includes a requisite analysis of the halakhic issues involved in Jewish education for girls. But Sarah Schenirer wrote about Torah as if the Torah she was teaching was Torah in its entirety, and as if it was entirely clear to her that this Torah was directed to women as much as to men (and directed at them first, as the verse from which the title of the school derives suggests).

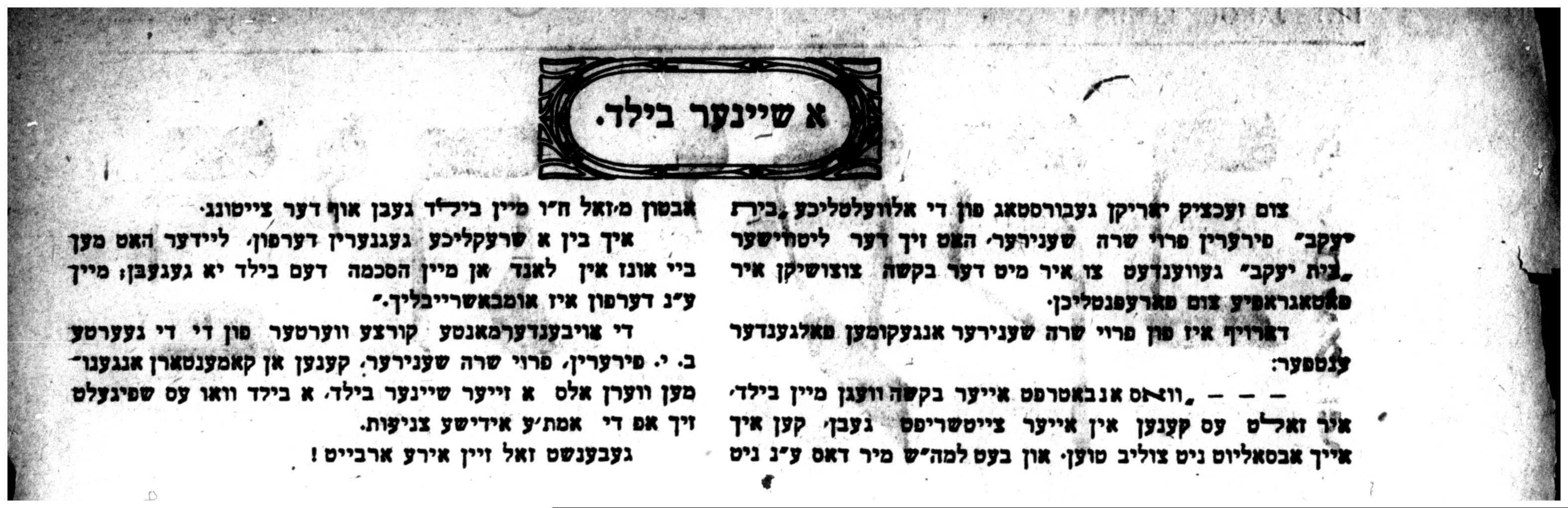

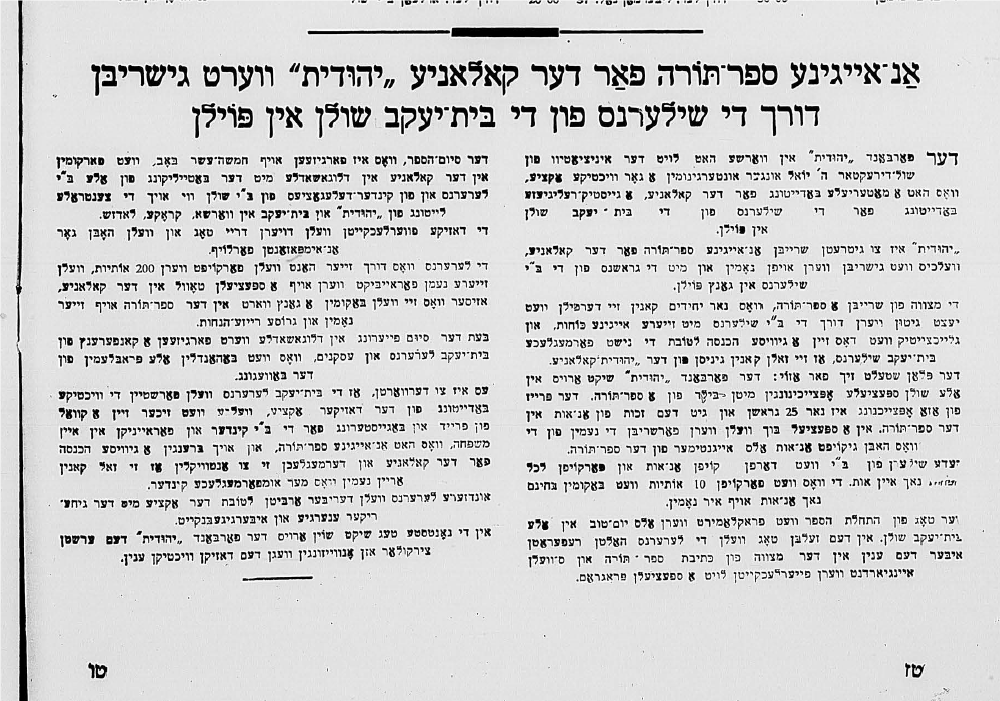

Here, for instance, is the opening of her mission statement for the Bais Yaakov movement, published in the first issue of the Bais Yaakov Journal (1923, six years after she opened her first school) and republished as part of Gezamlte shrift, what can only be called her “sefer” (which was the way the book was described in advertisements—as ‘the first sefer authored by a woman in many centuries’):

I think that by now everyone knows that the sole mission of the Bais Yaakov schools is to educate Jewish girls so that, with all their strength and with every breath, they will serve the Creator and fulfill the commandments of the Torah with seriousness and passion. . . .The Torah is directed at everyone: to the individual and the collective, priest and Israelite, educated and simple, judge or worker, prophet and ordinary man. The commandments must be fulfilled in the home and in the field, in private life as in society, in the Temple as on the street, in a business as in a workshop. It opens one’s eyes to see the divine power in nature, recognize Providence in the workings of history. It teaches us to understand our place among the nations. The Torah demands from us that we ‘impress these words upon your very heart’—and that we should spread its ideals in the world, ‘and teach them to your children—reciting them when you stay at home and when you are away’, whether we are asleep or awake from sleep, it must be the one straight line that we walk as we lead our lives, the crown on our heads, the watchword of our domestic and public lives—‘on the doorposts of your house and on your gates’ [Deut 11: 18-21].

Understand, Jewish women and girls! For thousands of years the Jewish people lived with the Torah. Millions of great men and women drew all their emotions, thoughts and values about everything in life from its holy fire. The national treasure that we labored for from time eternal has always been: the study of Torah.

While the men who supported Sarah Schenirer regularly discussed the halakhic ramifications of teaching girls Torah, Schenirer – here and elsewhere – simply talks about Torah as if it were clear to her that women participated in its study alongside all other Jews. The sentence “The Torah is directed at everyone: to the individual and the collective, priest and Israelite, educated and simple, judge or worker, prophet and ordinary man” is striking in not even mentioning men and women—the primary distinction referred to in rabbinic discussions of Torah study.

Whatever strategic impulses may have led Schenirer to avoid discussing what Rabbi Eliezer may have thought of her enterprise, she helped construct an alternative value system that shaped my own attitude to the Jewish library.

Maybe my failure to fall in love with Talmud is just the result of a deficit in my Jewish education.

But it was also part of my Jewish education that this was no deficit at all.

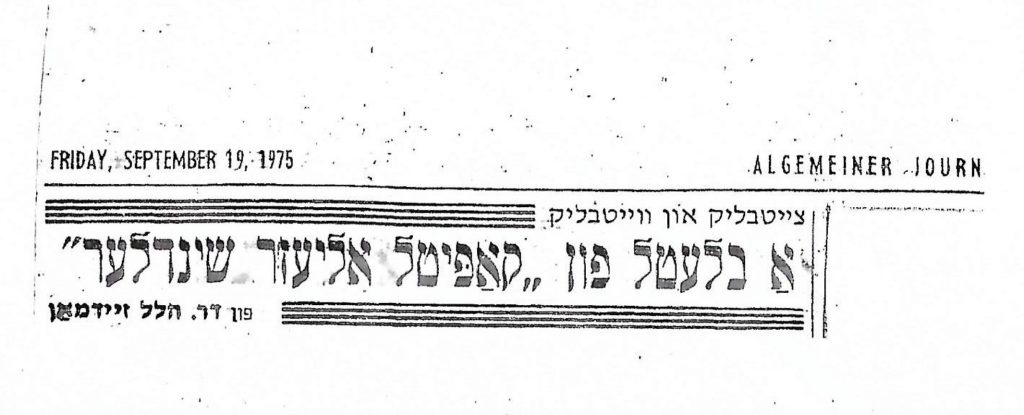

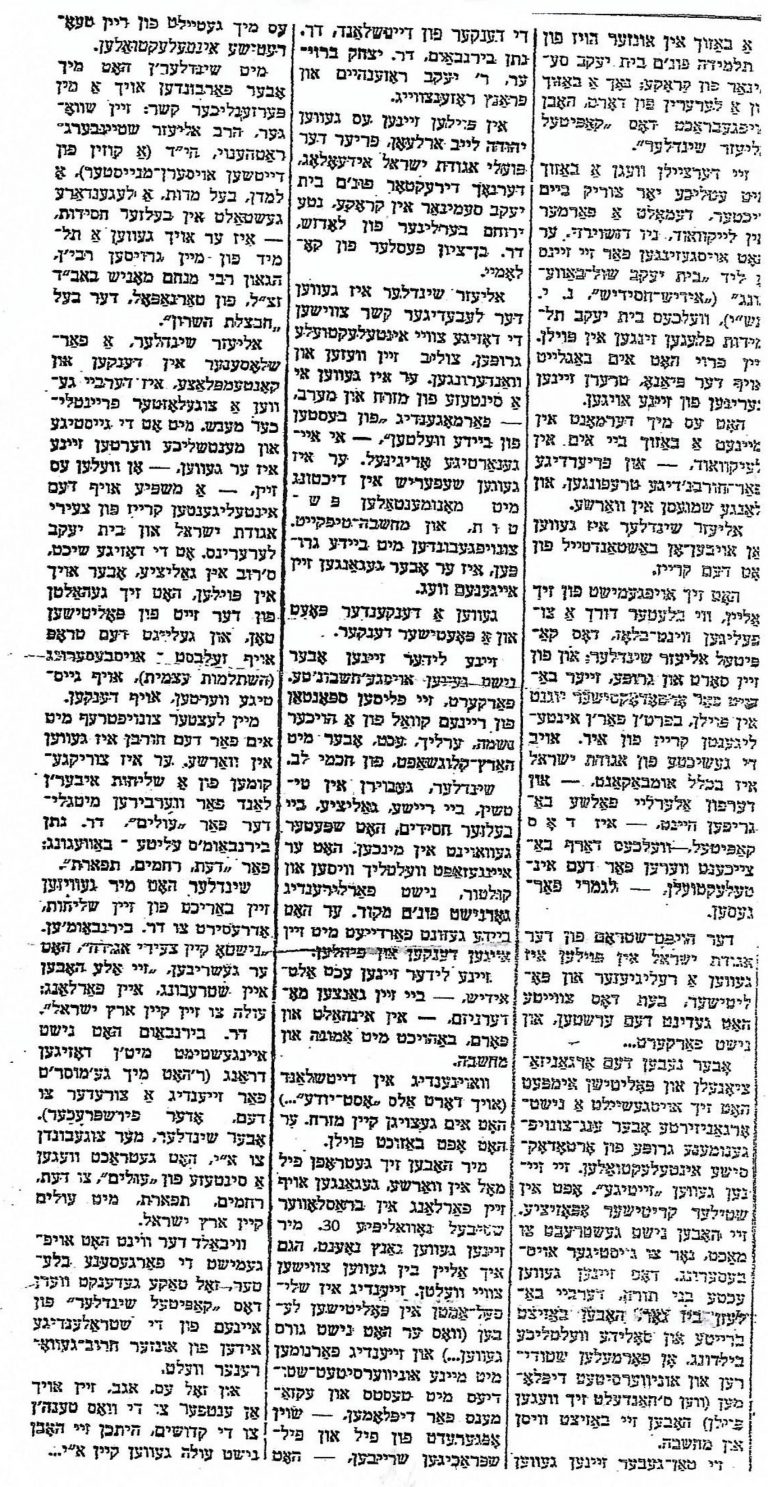

Naomi Seidman is the Chancellor Jackman Professor of the Arts in the Department for the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto and a 2016 Guggenheim Fellow; her 2019 book, Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition, explores the history of the movement in the interwar period.

The article goes on to describe the efforts to raise funds for the Sefer Torah and for scholarships to the camp throughout Poland, with girls buying letters and schools taking the opportunity to teach the laws of the Torah scribe, and the mechanisms of inscribing a Torah. Teachers who raised funds for 200 letters would have their names inscribed on a special plaque in the camp. The installation of the Torah scroll, the report continues, took place beginning on Tu Be’Av in the camp, with festivities, a conference, and other programs going on for three days. As it concludes, the act of collectively inscribing a Bais Yaakov Sefer Torah would certainly create a groundswell of joy and enthusiasm for Bais Yaakov girls, “uniting them in one family, which has one Sefer Torah.”

The article goes on to describe the efforts to raise funds for the Sefer Torah and for scholarships to the camp throughout Poland, with girls buying letters and schools taking the opportunity to teach the laws of the Torah scribe, and the mechanisms of inscribing a Torah. Teachers who raised funds for 200 letters would have their names inscribed on a special plaque in the camp. The installation of the Torah scroll, the report continues, took place beginning on Tu Be’Av in the camp, with festivities, a conference, and other programs going on for three days. As it concludes, the act of collectively inscribing a Bais Yaakov Sefer Torah would certainly create a groundswell of joy and enthusiasm for Bais Yaakov girls, “uniting them in one family, which has one Sefer Torah.”