Among my favorite Bais Yaakov finds in the YIVO archive, and one I discovered almost at the very start of my journey, is Undzer Gyzang: Lider far Bais Yaakov shuln, Basya Farbands, un Bnos Agudath Israel organizatsiyes [Our Song: Songs for Bais Yaakov schools, Basya Unions, and Bnos Agudath Israel organizations], published by the Bais Yaakov Press in 1931. The songbook hardly counts as a book—it’s a stapled pamphlet of seven pages, with lyrics and music for only four songs: “Bais Yaakov gezang,” “Basya lid,” “Antikelekh,” and “Bnos Hymn.” Compared to the Collected Writings of Sarah Schenirer, or the 137 issues of the Bais Yaakov Journal, some of them dozens of pages in length, the pamphlet didn’t at first seem like a major resource for understanding the movement.

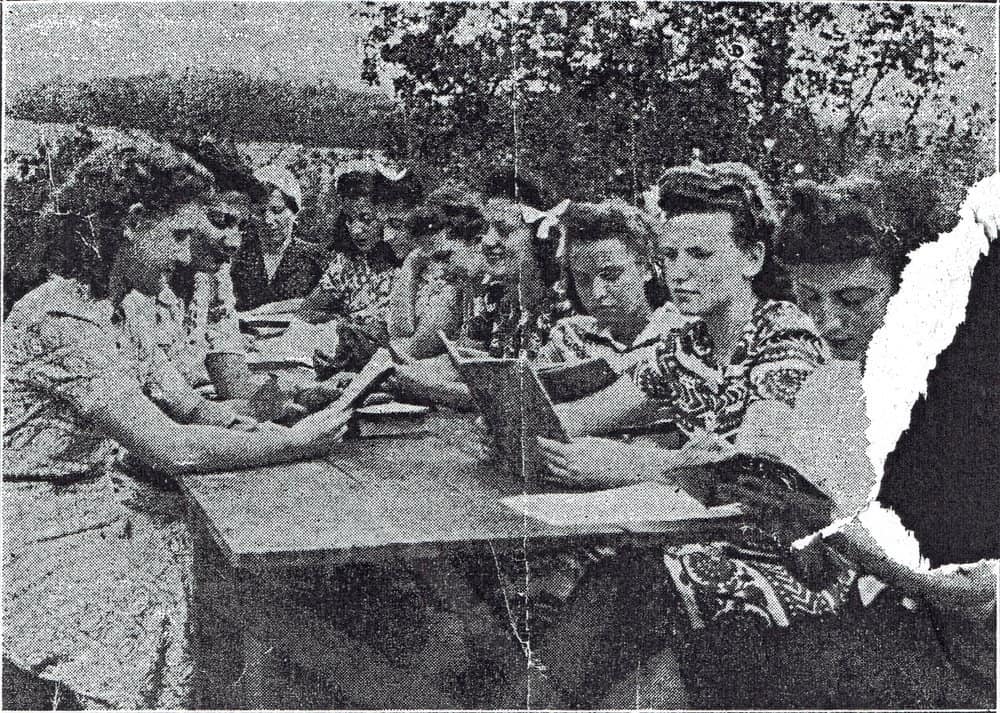

It is only in retrospect, years after I first paid a dollar or two to have it reproduced, that I understand this songbook for the treasure that it is. Memoirs and newspaper reports describe the importance of singing in the interwar Bais Yaakov, where girls prayed, sang, and danced together in the school, at special events and gatherings, and on hikes up the mountains during summer programs.

Rachel Feygenberg, an important secular poet and literary critic, described the locals and tourists who would congregate outside the Bais Yaakov of Kalisz on Friday evenings, listening to the voices of young girls singing Lekha Dodi.

On the third of Sivan, when Bais Yaakov celebrated the verse in Exodus that introduced the story of the giving of the Torah on Sinai and from which it derived its own name—‘ko tomar leveit Yaakov vetagid levnai yisrael’ [so shall you say to the House of Jacob and tell to the Children of Israel]—the students sang this verse as they danced in circles around Sarah Schenirer.

These tunes do not appear in the songbook, which records songs composed for the school system and one Yiddish poem set to music. But the songbook provides us with the music and words for another equally innovative feature of the movement: school songs.

While many of the tunes sung in Bais Yaakov were no doubt shared with larger Orthodox circles, three of the songs in the songbook were composed specifically for Bais Yaakov, as part of the burst of literary and organizational creativity that energized the movement in its earliest decades. The fourth, a poem by the Orthodox poet Miriam Ulinover, was apparently set to music for the movement, as well.

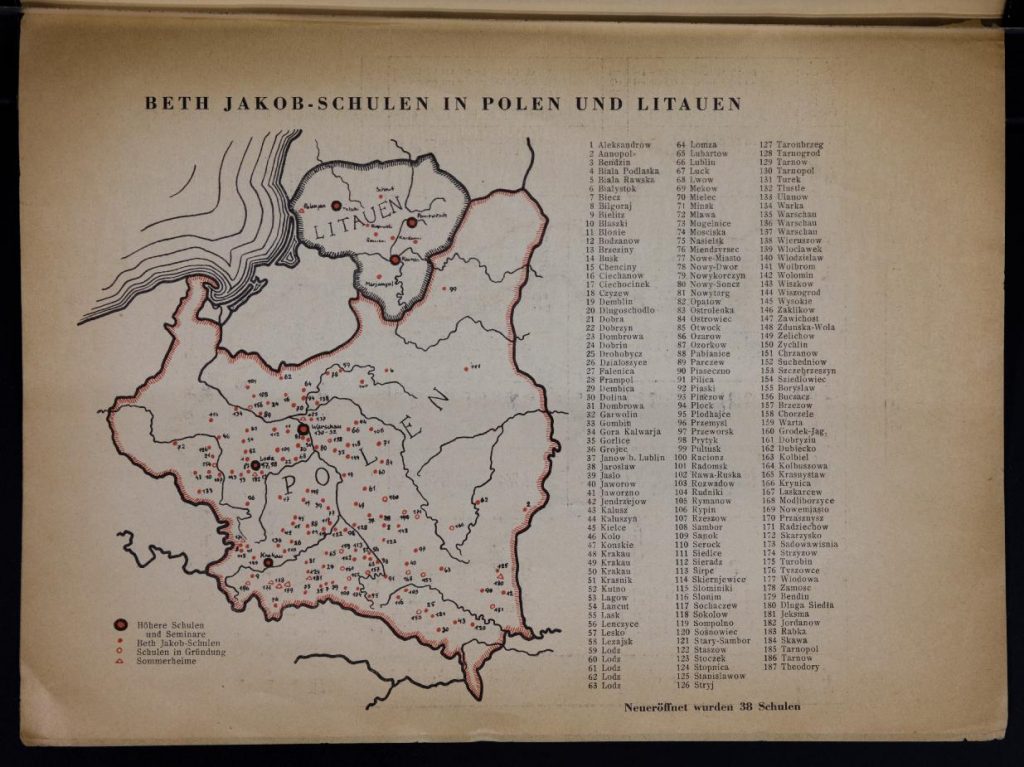

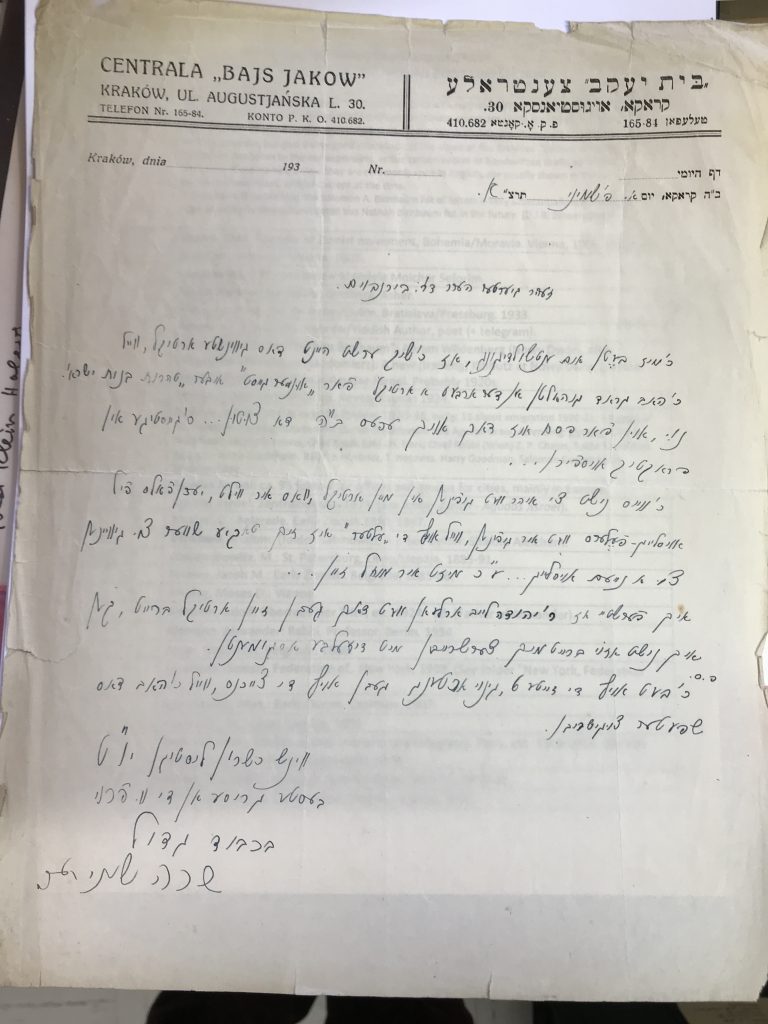

School songs are a feature of interwar Bais Yaakov as a “total institution” (as Devorah Weissman described it), which created its own culture of camps, schools, publications, slogans, youth movements, leadership roles and songs. The songbook records a song for Bais Yaakov schools; another song for Basya, the youth movements for young girls; and a third one for the Bnos organization—the youth movement for adolescent girls. Published by the Bais Yaakov Press, it demonstrates the administrative efforts to unite the far-flung chapters and schools under a single banner and aural signature.

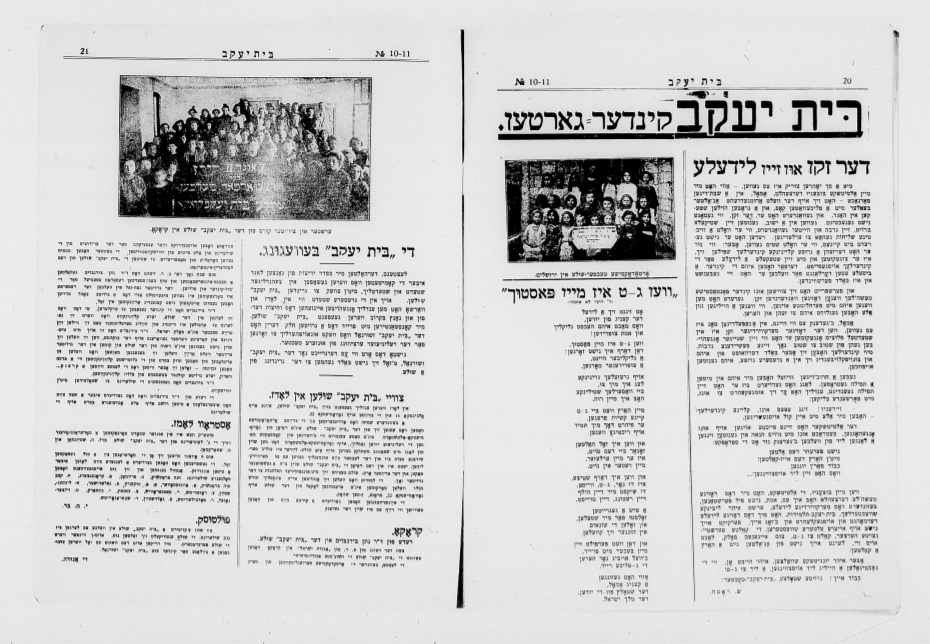

Along with the songbook itself, the archives also yield some context on how it came to be. A 1929 issue of the Bais Yaakov Journal announced a competition for the best anthem for the Bnos movement, a contest that was apparently won by Shmuel Nadler, whose “Bnos Hymn” appears in the songbook and was published as well in the journal.

And with the names of these writers and composers in hand, I was able to locate another treasure trove of Bais Yaakov and Agudah material in Yidish un Hsidish, a 1950 poetry and song collection published by Eliezer Schindler, who wrote the “Basya Lid” and “Bais Yaakov gezang.” This later collection includes not only those songs, but also a song for the Tse’irei Agudath Israel boys youth movement, an anthem for the Oylim youth movement, a poem about Sarah Schenirer, and yet another Bnos anthem—one that apparently did not win the prize!

With the 1931 songbook and the Bais Yaakov-related material in Schindler’s 1950 collection, we can now begin to hear something about the movement at its interwar height, rather than only reading words or notes on the page. Of the six or seven songs now in our possession, only one—“Bais Yaakov Gezang”—is still remembered and sung today. As you may notice, the song in the songbook has no chorus. But Dainy Bernstein remembered a rousing chorus, sung by her mother: “Lomir ale geyn in toyres veg’ [Let us all go in the path of Torah]. This chorus, provided through the route of oral transmission, has allowed us to fill in something to which the archive gave us only partial access.

Basya Schechter arranged the songs from Undzer Gyzang, among others Naomi found. She has performed the songs, with other graduates of Bias Yaakov, to accompany several of Naomi’s lectures so far. A larger project of arranging and recording these songs is in process. Basya, in consultation with Naomi, continues to perfect the tunes to best represent and bring to life the songs of Bais Yaakov in interwar Europe.

Below are some moments from Basya’s first performance of these songs, shortly after she began to work on the arrangements, at UPenn in November 2018.

Watch the full video, including Naomi’s lecture, on UPenn’s website. Many thanks to the staff at UPenn for this recording.

But this complex process, of archival discovery bolstered by living memory, describes the enterprise of Bais Yaakov history writ large. So much is so passionately remembered, and yet, so much is still lost or lies forgotten in the archive. The Bais Yaakov Project hopes to mine both types of memory in bringing to life the “antikelekh” of our own history.

Naomi Seidman is the Chancellor Jackman Professor of the Arts in the Department for the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto and a 2016 Guggenheim Fellow; her 2019 book, Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition, explores the history of the movement in the interwar period.