Among the hundreds of oral histories collected by the Spielberg Shoah Foundation are about fifty that mention Bais Yaakov as part of descriptions of life in prewar Poland. The interviewers, who seem to be following a rough script, generally ask what was taught in the schools.

But that might not be the right question.

For many graduates, it’s not what happened inside a classroom that made the most vivid impression, but rather the extra-curricular activities that were part of the Bais Yaakov experience.

In particular: the Bais Yaakov play.

Yaffa Gora relates in her memoir that plays were an important way the movement marketed itself. Bais Yaakov plays were often the most exciting event in a small town, and even girls from irreligious families sometimes pressed their parents to allow them to go to a Bais Yaakov, just for the chance of being in a play. These plays were part of Bais Yaakov culture not only in the small towns. The students at the Teachers’ Seminary in Kraków, for instance, wrote plays–comic sketches–in which girls gently poked fun of their teachers, or of the culture they were helping to create.

Even a student as serious as Vichna Kaplan, as Basya Bender relates, was not above playing the role of a goat in one such play. This was a goat famous in Bais Yaakov circles, hanging around the study groups that formed in the lap of nature in the Bais Yaakov summer colonies.

These plays, with their opportunities for girls to dress as the biblical character of Joseph or one of his brothers, as the Assyrian general Holofornes or the beauteous Judith, as a cantonist drafted into the Tsar’s army or the devastated mother left behind, or as Chana or one of her seven sons, were expansions of what Bais Yaakov was already doing: creating roles for Jewish girls to explore that were both new and traditional (as they were both male and female).

Sure, Bais Yaakov was training girls in the roles of Orthodox teachers, wives, and mothers.

But along the way, the variety of roles that might be filled, characters that might be inhabited, ranged far beyond those three.

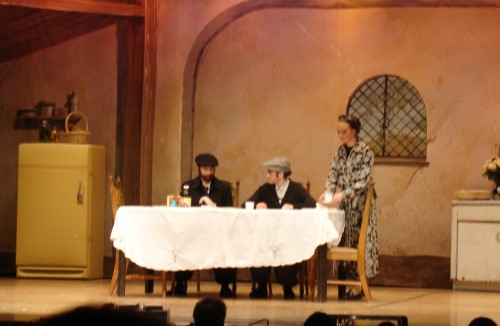

Some of the plays, as in the Seminary, were for internal Bais Yaakov audiences. But in the small towns, they tended to be rather elaborate affairs. Rehearsals went on for months, posters around town advertised the performances (“entrance for women only”), and the play was staged in such public venues as movie theaters.

Nor was this entirely amateur theater. We have seven or eight published scripts that Bais Yaakov made available to its school directors, including five by Sarah Schenirer. This much attention to theater could hardly go unnoticed.

Indeed we have many photographs of Bais Yaakov classes in their costumes, and one or two of the sets, as well.

The Yiddish press was fascinated by the phenomenon, and so, apparently, were people who might be expected to be outside the strict orbit of Bais Yaakov theater. At least two newspaper stories in Yiddish dailies report on boys who dressed in women’s clothing in their attempt to sneak into Hanukkah plays. Hanukkah, in addition to Purim, was theater season in Bais Yaakov.

In both these instances, cross-dressed boys in the audience were watching cross-dressed girls onstage. (The accounts may be entirely fictional – the Yiddish press was often sensationalistic and loved juicy stories about Bais Yaakov.) Gender segregation, the mark of the traditionalism of Bais Yaakov, also seemed to invite some of the more free-spirited and radical of its cultural expressions.

The importance of theater in Bais Yaakov culture, both for the participants and those who served as the various audiences and spectators invited by these performances, might explain one of the more curious stories I discovered in the Yiddish press: on February 22, 1933, the Warsaw daily Hayntige Nayes reported that Agudah had undertaken a filmmaking project, with the script written by Sarah Schenirer and the story about the Chmielnitzki Massacres of 1648-49.

The story can hardly be taken at face value: Among the elements that give it away as fiction, or as farce, is the detail that Sarah Schenirer had set sail to scout for locations for the film, which was to be shot in both Poland and Palestine—we know for a fact that Schenirer longed to visit the Land of Israel, but never succeeded. (In the late 1930s, a plan to bring her body to Jerusalem was formulated, without success).

The story, as fantastic as it seems, is not entirely implausible. With so much energy devoted to Bais Yaakov theater, why not film? And who better to write the script than Bais Yaakov’s foremost playwright?

Might a few old reels of such a movie turn up one day in some dusty Polish archive?

Unlike many other aspects of interwar Bais Yaakov, the play is alive and well.

I participated in Bais Yaakov plays s a student in Bais Yaakov Academy in Brooklyn and a camper in Camp “Tubby” Tikhon Bais Yaakov in the 1970s, in the same tradition as the plays from the 1920s and 1930s.

I loved playing a street urchin in The Rothschilds, painting the set for The Diary of Anne Frank, and getting stuck under the stage as Slightly Soiled in Peter Pan (not all the plays were on Jewish themes).

The astonishing story of the founding and growth of Bais Yaakov is regularly staged in schools around the world.

But Sarah Schenirer’s own scripts, like Ḥanah un ihre ziben zuhn : hisṭorishe forshṭelung in eyn aḳṭ, are still available at YIVO and no doubt elsewhere.

Perhaps the time has come for that repertoire to be revived?

Bais Yaakov girls performing in “Listen With Your Heart,” Bais Yaakov High School in Brooklyn, 2005.