During the March 20-21, 2023, [or 27-28, Adar 5783] conference “Bais Yaakov in Historical and Transnational Perspective,” I was suddenly immersed in the world of Bais Yaakov scholarship. Submerged in the intricate semiotics of this subsection of a subsection of frumkeit, I gained an awareness of how large Bais Yaakov looms in Orthodoxy history. What distinguished this group of scholars, anthropologists, historians, and literary critics, some OTD, others very much on the path, and others male, was that their focus on Orthodox Jews was squarely on what might seem a marginal group within it–Orthodox girls. The conference reminded me of the battle cry “Girls to the Front!” of The Punk Singer herself, Kathleen Hanna, in her Bikini Kill days. So if you are with me, I am going to take you through the Bais Yaakov Conference through the lens of the riot grrrl manifesto to draw out and elaborate on what I witnessed, a display of feminist and punk scholarship. The title of the riot grrrl manifesto, HISTORY IS A WEAPON, was appropriate for a conference so immersed, after all, in history. But so is the rest of the manifesto, as far as it may seem from the academic and heymish world of the conference. The manifesto is a series of lines, each beginning with the word BECAUSE:

BECAUSE viewing our work as being connected to our girlfriends-politics-real lives is essential if we are gonna figure out how what we are doing impacts, reflects, perpetuates, or DISRUPTS the status quo.

Naomi Seidman’s book, Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition (2019), evoked this riot grrrl punk spirit by unapologetically centering women and, more precisely, girls. The Bais Yaakov movement originated in Poland and spread across the European continent and the globe, transforming and reshaping itself to its new contexts, swimming with or against the currents of Orthodoxy and in the process shaping generations of girls across the globe. Entangled with her work on the Bais Yaakov Project, the conference embodied the momentum of Seidman’s more-recent efforts to document and collaboratively explore this history.

From the beginning of this two-day conference, it was evident that the gathering was not just another intellectual forum, along with others regularly convening under the roof of the Department for the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto. Rather, it was a tribute and celebration of Sore Schenirer, founder of the school system. The conference, falling on the heels of Schenirer’s Yahrzeit, was in some sense a spiritual continuation of Schenirer’s legacy, as Seidman remarked in her opening comments.

This earnest connection to Schenirer evokes a relationship beyond the present generation. Throughout the conference, the presenters, both scholars and community members, spoke of the vast reach of Bais Yaakov. It would take the use of new methodologies to map, new theories of social network analysis, to see and conceptualize these global connections, and to help others see them on the website.

BECAUSE we wanna make it easier for girls to see/hear each other’s work so that we can share strategies and criticize-applaud each other.

Matching the global reach of Bais Yaakov, the conference was supported through multi-institutional partnerships between co-sponsors at the University of Toronto, York University, Fairfield University, and the University of Wroclaw. Seidman did not shy away from pointing out that all of the representatives of these institutions were “dudes.” Unlike the former Bais Yaakov girls around the table, these men came to study Bais Yaakov as outsiders to the highest degree, in a field in which both the objects of study and the scholars have fallen into patterns of sexual segregation. The invitation to “outsiders” was deliberate, encouraging scholars of Hasidism and Yiddishism and Orthodoxy to allow girls’ and women’s voices to come to the forefront and to rethink their scholarly research agendas along the way. It is a radical and necessary reconfiguration of Jewish Studies to hold an academic conference where men are the minority (and not a particularly vocal minority, either).

BECAUSE we don’t wanna assimilate to someone else’s (boy) standards of what is or isn’t.

Even under this utopian Amazonian vision, the first session, “Bais Yaakov Contexts,” featured talks by Glenn Dynner (Fairfield University) and Wojciech Tworek (Wroclaw), and accordingly, both papers looked at Bais Yaakov through a male Orthodox gaze–a stumbling start in an otherwise female-dominated discourse. Dynner’s paper approached the normalization of girls’ Torah study in schools in the context of Orthodox opposition to secular Yiddish and Hebrew education or assimilationist Polish. Tworek’s paper sought to find evidence of Bais Yaakov’s unofficial relationship with Chabad in Interwar Poland. These papers evoke a previous gap in the study of global Orthodoxy and provide context for the inhospitable environments in which Bais Yaakov emerged.

BECAUSE doing/reading/seeing/hearing cool things that validate and challenge us can help us gain the strength and sense of community that we need in order to figure out how bullshit like racism, able-bodieism, ageism, speciesism, classism, thinism, sexism, anti-semitism and heterosexism figures in our own lives.

Session two included a pre-recorded lecture from Joanna Degler (Wroclaw) on Sore Schenirer’s Polish diary. Degler’s findings show the influence of Polish feminist public lectures on Schenirer in the years before she founded Bais Yaakov, which stood in some tension with the speakers in the first session, emphasizing how Bais Yaakov saved girls from secular Polish influence. In 1994 Irena Klepfisz penned an essay on Yiddish women writers titled “Queens of Contradiction”—yet the case of Bais Yaakov may usurp, or at the very least, rival that title. Following Degler was a paper expressing one such contradiction. Kalman Weiser (York University) spoke of Solomon Birnbaum’s Yiddish spelling system, which reflected Orthodox ways of speech and pushed against secular Yiddishist YIVO standardization; this system garnered approval from Sore Schenirer herself. Schenirer thus was influenced by Polish and secularizing forces while maintaining the distinctiveness and richness of Orthodoxy in developing her schools. Dainy Bernstein (University of Pittsburgh) and Nechama Juni (Carleton College) embraced the legacy of these early choices that presently queer the experience of the Orthodox girls while maintaining the strength and ardency of Orthodoxy, whether intentionally or inadvertently.

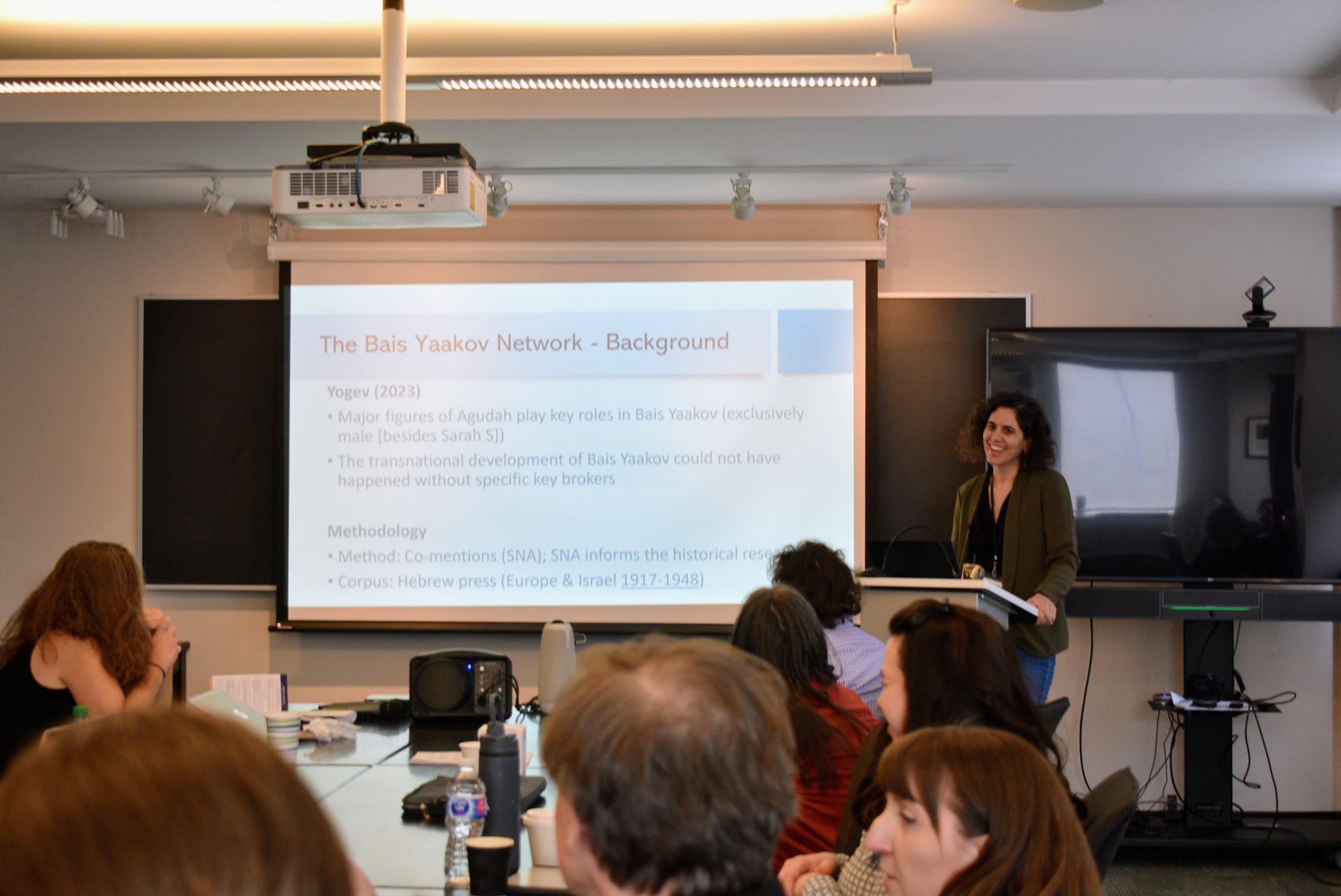

In yet another strategy to push forward Bais Yaakov research and align this research with cutting-edge digital humanities, Dikla Yogev (University of Toronto) and Marcin Wodziński (Wroclaw) co-presented on digital humanities methodologies for approaching the immense datasets from the archives. Through machine learning and social network analysis, Wodziński and Yogev argued that we should rethink our assumptions about centrality and power in both Hasidic dynasties and in Religious-Haredi networks. Thus, key players reveal themselves where once research may have ignored them or did not notice their existence. Recognizing a wider set of players in creating Orthodox culture than the better-known leaders shifts and broadens our way of understanding on community structure, social control, and leadership.

BECAUSE we are interested in creating non-hierarchical ways of being AND making music, friends, and scenes based on communication + understanding, instead of competition + good/bad categorizations.

The atmosphere of the conference even pushed for a rethinking of the term “Bais Yaakov Girls” at least in OTD, or mixed OTD and still on the derekh company. The singer M Miller suggested that “Bais Yaakov students” was a more apt term to describe the certainly self-selecting group who joined the conference either as participants or as performers. As became evident in my immersion in the world of Bais Yaakov, performance is more than welcomed and is, in fact, quintessential to the lived experience of being a Bais Yaakov student.

Performance is essential also in that there is a Bais Yaakov accent unique to those who grow up in the system; their Hebrew (and once Yiddish) are inflected uniquely and signal their educational background. Performance through dress is part of an Orthodox girlhood of long skirts. Performance was the central topic in session four. Leslie Ginsparg Klein (Women’s Institute of Torah Seminary and College) delivered a paper, “Snap! Clap! Snap! Clap!’ The Diversity and Uniformity of Bais Yaakov Education and Culture Across North America,” initiating performance from the Bais Yaakov alumni in the audience. Audience members from a wide age range erupted with “Jews from over the world” to Ginsparg Klein’s call “Snap! Clap! Snap! Clap!” The call and response dissolved the boundary between expert and audience, if only for a brief moment.

One could not remain a closeted Bais Yaakov alumni at this conference. While performance was not obligatory, it was almost second nature. The impulse towards performance may have been as a part of “production,” which Ginsparg Klein described as a hallmark of the Bais Yaakov experience, where girls come together in musical, theatrical, or dance revues; they are involved in every step of the process of orchestrating a professional quality performance. Seidman’s own paper, “Acting Like a Bais Yaakov Girl: Gender, Piety, Performance,” looked at the roles that the Bais Yaakov schools enable young girls to play, from male and female roles to Jewish variations of secular plays, with stage directions taken from both Hollywood and rabbinic authorities. Transgressive performances of Orthodoxy were staged in the Polish spa town of Rabka in the 1930s, as Ula Madej-Krupitski (McGill) explained: Rabka was a popular destination for many Jewish families and Bais Yaakov girls during the interwar period. In the countryside, the students would experience certain girlhood freedoms while playing the part of their fall-through-spring selves for visitors.

While the performance and empowerment of these girls may displace us from their context in Orthodox—now Ultra-Orthodox circles— due to their clearly radical flavor, these other modes of performance remind us that Bais Yaakov schools succeed not through the overthrow of norms but rather through normalizing local Orthodox mores, whatever those might be.

BECAUSE we see fostering and supporting girl scenes and girl artists of all kinds as integral to this process.

The first day culminated with an ensemble performance led by Basya Schechter, with M Miller and the Kol Isha choir. Kol Isha evokes the prohibition for men to hear women singing and simultaneously recalls the punk-infused recentering of women’s voices, this time in a literal sense. Kol Isha, comprising a number of former Bais Yaakov students from Toronto, backed up Basya with instruments in hand and ecstatic vocal harmonies. Together they brought to life some of the Bais Yaakov songbooks. Basya, recalling their Bais Yaakov education and with the choir nodding in agreement behind her, described how she had no formal musical training but rather learned “music from the soul.” Former Bais Yaakov schooling experiences layered themselves on the individuals standing before the audience, and it was clear that still, to this day, in every song they performed, there was improvisation, playing as a collective by channeling deep within the individual—the soul led, and the rest followed. The rising and swelling of the music exemplified the mystical energies of chasidus with the re-gendering of lyrics and the swapping of “acceptable” gender roles by the performers. Or, as Basya explained, this is the alt-nay–old/new.

BECAUSE we recognize fantasies of Instant Macho Gun Revolution as impractical lies meant to keep us simply dreaming instead of becoming our dreams AND THUS seek to create revolution in our own lives every single day by envisioning and creating alternatives to the bullshit christian capitalist way of doing things.

The second day of the conference included more Zoom papers than in-person speakers, mirroring the transnational reach of Bais Yaakov. In session five, “Bais Yaakov and the Agudah” Ilan Fuchs (American Public University) brought forward the forgotten history of Orthodox Socialism in the interwar period; Nathan Cohen (Bar Ilan) presented the literature that Bais Yaakov Press was publishing, as reading material for its students; and Iris Brown (Ono Academic College) explained how and why the Agudath Israel founded youth movements for girls as a second front (after the school system) against assimilation. In all three of the papers, Orthodox politics, education, and engagement with youth were explored as richer and more complicated than might seem.

BECAUSE we are angry at a society that tells us Girl = Dumb, Girl = Bad, Girl = Weak.

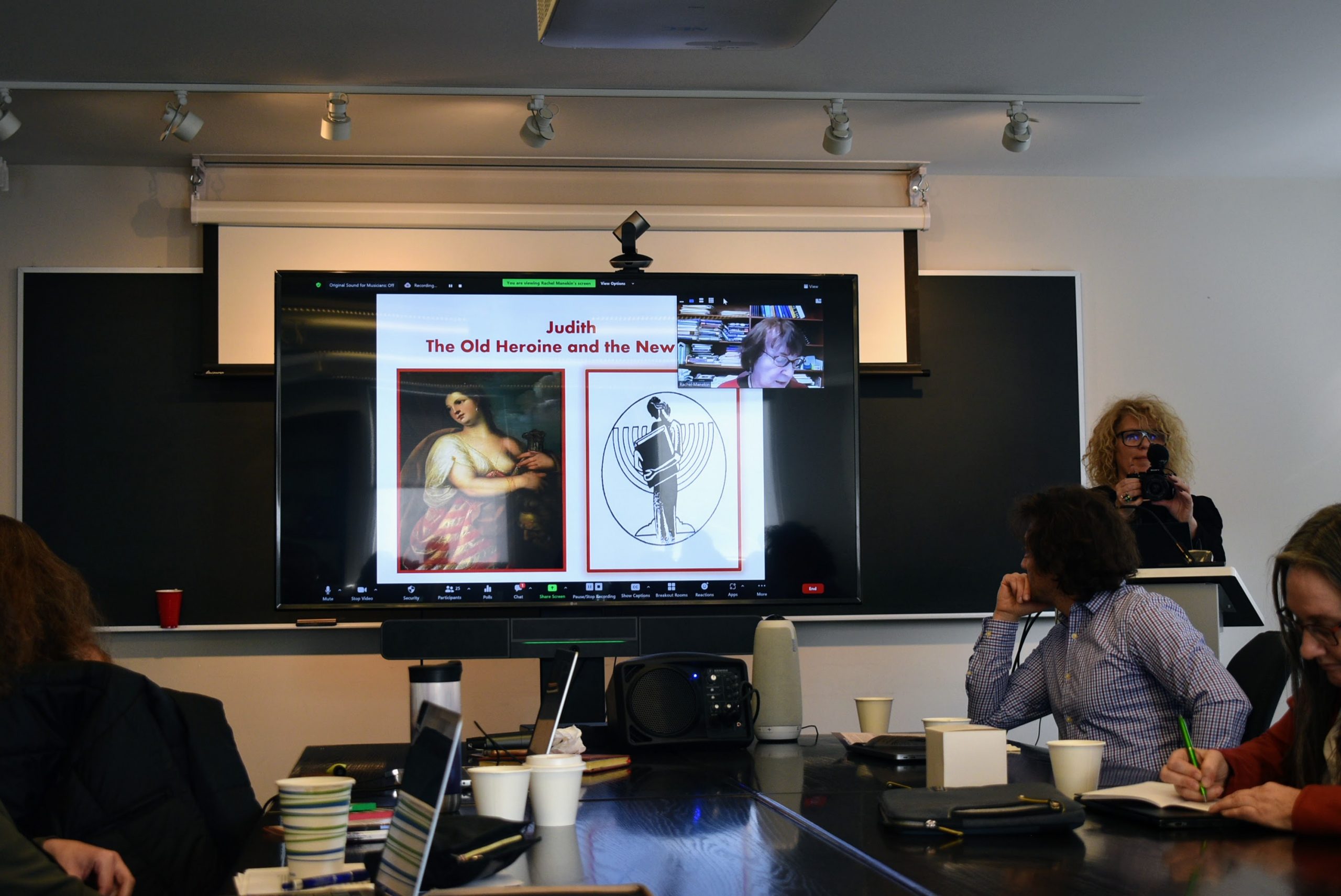

In session six, “Bais Yaakov in Transnational Perspective,” Rachel Manekin (University of Maryland) complicated the enthusiastic portraits put out by the Bais Yaakov schools by presenting the diary of an unhappy, philosophically tormented, and exploited Bais Yaakov teacher; Michal Shaul (Herzog College), focusing on post-Holocaust Israel, spoke about the development of Holocaust education in ultra-Orthodox Israel contexts. Mari-Masha Yossiffon (University of Toronto) zoomed in from Buenos Aires, where she presented the findings from her fieldwork, where four different Bais Yaakov schools serve different parts of the community. The final session included a surprise from Nomi Levenkron (Kinneret College, Tel Aviv University, and Hebrew University), who shared her research on Miriam Brunner, a Bais Yaakov teacher and terrorist (freedom fighter?) in an Israeli Ultra-Orthodox underground. Tzippora Weinberg (NYU) presented her case for the distinctiveness of Bais Yaakov in Lithuania, where Bais Yaakov was not a school system but rather a network of women’s Torah study on the highest level; Weinberg argued that, in Lithuania, this was Torah “for its own sake,” rather than–as in Poland–to serve other purposes. Yogev concluded the day by demonstrating how social network analysis could illuminate the symbolic or real power of women in the network, focusing on both Sore Schenirer and some of the most famous among her students, the legendary 10 women who survived Auschwitz together.

BECAUSE we must take over the means of production in order to create our own meanings.

The conference proper ended with a concluding conversation. Along with showcasing the Bais Yaakov Project website, the conference participants were also invited to reflect: Where do we go now? Who wasn’t a part of this conversation that should have been? Finally, what does it mean to have an academic discourse centered on girls and women in which very few male scholars have devoted their energies? Perhaps this conference might signal a new era in which the feminist scholars and former Bais Yaakov students who paved the way for this field will be joined by others with different scholarly agendas and social locations.

But the conference wasn’t yet over: For those not rushing off the airport, there was a trip to the Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto to view Bais Yaakov resources from the Nathan and Solomon Birnbaum Family Archive and Seidman’s personal Bais Yaakov archive. Among the photographs and Bais Yaakov journals, an apron lay screen-printed with the paragon of Jewish womanly virtue, a true balebusta, lighting candles, hands waving before her, with her son looking on. Her natural hair was possibly covered twice over, signifying deferential piety along with her long sleeves. There she lay, screen-printed on a kitschy apron, framed by the words “HAPPY HOLIDAYS” and “BETH JACOB SCHOOL,” the English spelling sign of a temporary more-Americanizing moment of Bais Yaakov history—another Queen of Contradictions.

BECAUSE I believe with my wholeheartmindbody that girls constitute a revolutionary soul force that can, and will change the world for real.