The apocryphal Holocaust story of the 93 Bais Yaakov girls who committed suicide rather than be taken as prostitutes by German soldiers is well known in Orthodox circles, and has been the subject of poetry, plays, and memorial events. In 2012, as far as we know for the first time, it also became the subject of a novel. Na’arot lemofet (“Well-Educated Girls”), a psychological thriller by the Hebrew writer Sarah Blau (born 1973), is mostly set in the religious city of Bnei-Brak where Blau was raised but it also includes scenes that take place in the Bais Yaakov Seminary building in Krakow, in the room where the girls were held in their final hours. Please also see our next blog, which includes an English translation of an excerpt of the novel.

The novel, which takes place in the 1980s, unfolds within the world of a religious girls’ high school in Bnei Brak, where a student named Chava Keller is determined to produce and star in a play presenting the story of the ninety-three. Into this drama of theater-crazy high school girls (so familiar in Bais Yaakov culture), Blau weaves something like a diary recounting the story of the ninety-three from the point of view of Chaya Feldman, the young woman whose name is signed to the letter that informed the world of their fate (which was sometimes referred to “The Last Will and Testament of the Ninety-Three Martyrs”). Feldman, in these passages, reveals a different story, one that subverts what we think we know about her and the myth of the ninety-three.

Chava Keller, the heroine, is an orphan, raised by her uncle and aunt. Her mother, Dina, who died while giving birth to her, conceived her out of wedlock and never revealed the identity of the father. When her mother was seventeen, she attempted to put on the play about the ninety-three herself, but during the production, her pregnancy was revealed, and she was ignominiously expelled from the school. Her friend, chosen to take her place as the lead character of Chaya Feldman, mysteriously disappeared shortly thereafter and the play was never performed. With Chava trying to put on the same show, the events of the past are threatening to repeat themselves.

The novel thus tells the story of different generations–the mother, the daughter, and the myth of the ninety-three that shadows them both. Part Bildungsroman and part crime novel, following the mystery of where these girls have disappeared to, it also focuses most persistently on the myths and stories told to young girls and women to teach them modesty and Orthodox values. Others have long ago dissected the myth of the 93. What Blau does is show the power, and dangers, of myths like these.

Last June, we sat down to discuss the myth of the ninety-three Bais Yaakov Girls, what it means to be a good girl, and why this story is still so relevant today. Before I had the chance to ask when she had first heard the story of the ninety-three, Sarah started our conversation by anticipating just that question:

Sarah Blau: When this book was first published, a question that came up consistently in interviews was how I had come to know about the ninety-three? When did I first hear that story? And I just can’t remember. It’s as if I asked you: ‘When was the first time you heard about Cinderella? When was the first time you heard of Snow White?’ It was always there.

I grew up with this story. The “Garden of the Ninety-Three” was located next to my house in Bnei Brak, and we played there throughout my childhood. This ghost story was always present.

Miriam Schwartz: Can you remember if you heard about it in school or at home? Or when did they tell you all the details?

Sarah: So, as I said, this story was always there. But it’s true that in school, in the Ulpana (high school) “Emuna” I went to, which was not a Charedi school (it belongs to the national-orthodox stream. M.S), the story was told on Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Not on every Holocaust Remembrance Day as I describe in the novel, but on some of them, the last will of the ninety-three was read out loud. My memory of school is now mixed up with the story I tell in the book, but I think that the story of the ninety-three was mentioned often in those days. Similar narratives also appeared in books I read. For example, there was the book “I Believe” (by M. Eliav. M.S) that focused on stories about faith in the Holocaust, stories of people who refused to eat on Yom Kippur or refused to eat pig’s fat and died of hunger because of their faith. And there was also the book “To Vanquish the Dragon” (by Pearl Benisch. M.S.) published by Feldheim Press, which featured the story of the ninety-three.

Interestingly, when I was working on the novel many people mentioned “To Vanquish the Dragon” to me, so I bought it, and to my great surprise, the story of the ninety-three was not there anymore. I think that is proof that even in the Haredi community, which held on to this story as a real historic event for the longest time, even they doubt it now.

Miriam: Do you think today in Israeli schools the story of the ninety-three is no longer taught?

Sarah: I am convinced it is not taught in Israel. I talked with some Haredi women in Israel, and I went to a conference a few years ago and learned that they no longer teach it. The strongest evidence for me was that it was excluded from Feldheim’s most popular book (“To Vanquish the Dragon”).

This change in the perception of this story as a historical event is also evident through the change in the street signs in Israel: there are five streets named “The Ninety-Three Street” plus the garden in Bnei Brak. And if I am not mistaken, the signs were changed. It used to be “Street of the Ninety-Three: in memory of the 93 girls who committed suicide while calling shma Israel in the time of the Nazis” Today the sign reads: “Street of the Ninety-Three: girls and Jewish women in that number who, according to the story, chose to commit suicide so not to fall in the hands of Nazis soldiers in the Warsaw Ghetto or perhaps in the Krakow Ghetto”. Meaning the signs today acknowledge that this is a story that was perceived as real; this is phrased carefully not to claim that it had actually happened.

Today no one thinks that it is a real story. Now that I think of it, maybe the infiltration of the Internet into the peripheries of Haredi culture also affected access to information and played a role in this change. My guess is that today even in the Israeli Haredi community no one thinks it really happened. That said, the story is still told, but differently, not as a historical event but as an educational tale.

I was shocked when I found out it was not a true story. I remember it so clearly. I don’t remember how I first learned the story, but I remember very clearly how I found out it was not true. It happened while I was volunteering in National Service at the Institute for Holocaust Studies in Haifa. I started working there as a young girl of nineteen, just two years older than Chava Keller, the heroine of my novel, and like my heroine when I arrived there it was still such a meaningful story for me; the darkness of it drew me, not necessarily its pedagogical aspects, but I felt an unexplained combination of attraction and disgust towards it. I mentioned the story of the ninety-three to one of the other instructors and she told me “What do you mean… it is not real. It didn’t happen”.

I incorporated that exchange into the novel, when the police investigator talks to Chava. I remember telling her, “What do you mean it didn’t happen? What else didn’t happen?”. And then I read the important work of Professor Judy Baumel. Years later Prof. Baumel helped me in the writing process and was an unofficial academic consultant for the book. She was also the one who showed me the alleged handwritten will of Chaya Feldman.

Prof. Baumel has a theory about who wrote the will. She believes it was a German Jew who immigrated to New York. He saw what happened in Germany and was horrified that the world was ignoring it. The story was published in the New York Times in January 1943, and he wanted to shock people. The story received a lot of attention; it was 1943, long before people heard of Anne Frank or Mordechai Anielewicz. The writer wanted to rattle the Jewish world, and he wisely chose something that would work as a shocker. Because it is based on a myth that had already been passed along through the generations, the myth of the desecrated daughter of Israel. It is the story of a young Jewish girl who is desecrated by a non-Jewish man. He touched upon their darkest fears and pressed the most sensitive buttons of the Jewish consciousness. I believe he is a genius for conceiving this letter.

Miriam: That is fascinating. If his goal was to shake the Jewish world, why publish it in the New York Times and not in one of the popular Yiddish newspapers of the time?

Sarah: Interesting question. I estimate he wanted to reach the largest audience. The Jewish press alone does not count enough. Similarly, when I was a journalist for the Orthodox press in Israel, there was a certain disrespect towards it. If you wanted to get something out you had to get to the secular general press.

Miriam: Do you believe in Prof. Baumel’s theory regarding the man behind the letter or do you have your own speculations about who published it and their motives?

Sarah: I continue Baumel’s line of thought. Why do narratives stay with us? Why did this story catch people’s attention? Because it is based on truth, on previous tales, on the Talmud, and it has an educational value: better death than Bitter death.

I incorporated all those tales in my book–stories from the time of the Chmielnicki pogroms, like the girl who is forced to marry a Cossak and she tells him she has magic powers, so if he stabs her she won’t die, and then he does and she dies before the marriage is consummated. Or the girl who jumped into the river to avoid being forced to marry a non-Jew. Hence, death is better than forced marriage. The story of the ninety-three is based on other educational stories we were told. He did not invent this type of narrative. The narratives that work are those that are based on truth, and on previous myths and stories.

The story of the ninety-three was so effective; rabbis ordered people to fast in their memory, and women were ordered to light extra Shabbat candles for the ninety-three. In one of my lectures a woman came up to me to show me a candlestick with Hebrew inscription of צ”ג (these two Hebrew letters signify in gematria the number 93). It was so popular they had made special candlesticks for it.

From the educational aspect, we were taught that sex equals death. Later, the doubts crept in.

Sarah [to me:] Did you believe this story was real?

Miriam: No. But I only heard this story as an adult. Growing up in the secular education system in Jerusalem, we were not exposed to this story.

Sarah: Prof. Judy Baumel describes how those doubts arose. When survivors from Krakow immigrated to Israel in 1945 they were asked about Chaya Feldman and the ninety-three Bais Yaakov girls, since it was already so well known, but not one of the survivors heard of it. And slowly people started doubting it.

It is important to note that there were similar real incidents: a young Jewish woman, a secretary, was asked by her Nazi boss to sleep with her “or else”, and she committed suicide by jumping out of the window, leaving a letter behind. It is just like Chaya Feldman’s will, but the scale is different, she was one woman. And when you exaggerate the story, it becomes less believable and easier to disprove. The myth is not about one woman, but ninety-three women. That is so many girls, and families, how can it be that no one heard of it, the Jewish resistance, or the Jewish Council of the ghetto? And what did they do with the bodies?

Miriam: And the poison? Where could they have acquired ninety-three cyanide pills from?

Sarah: Even hospitals did not have cyanide at the time. And the decision itself, they all decided to kill themselves? All of them? When I was sixteen, we couldn’t choose a four-girl committee for our class.

Miriam: And there is also the unreliable tale of the ninety-fourth girl who escaped and heard what happened from outside the building without being caught herself and later published her recollections of the incident.

Sarah: Yes, it is a complete fairytale. But it blended perfectly with the Jewish narrative of the desecrated Jewish girl, and that is why people believed it.

One more thing we must say is: “It didn’t happen because we haven’t heard of it” is a problematic argument when discussing the Holocaust because there were entire communities that got wiped out and took their stories with them. But in this specific tale, in the Krakow ghetto, where there was a Judenrat (Jewish council) and many survivors, it does not make sense that no one heard of it. And how could the letter get to New York? There are just too many question marks.

But I believe in what I wrote in the novel in Chaya Feldman’s last chapter: “In many respects, I am more real than any reality, more present than any present, I have never existed more completely”. And the garden, the street names, the ghosts of the ninety-three are still there, and they won’t disappear so fast. The fact that the story is not true does not change the memory of it.

Miriam: I love that quote, and that Chaya Feldman in your novel is talking to the readers today, addressing us directly. What made you choose to give Feldman a voice in your novel?

Sarah: The simple answer is that at first I wanted to write a historical novel, with everything told from Feldman’s perspective. But I felt that I didn’t know enough and, more importantly, I understood that I am more interested in the story’s effect on the next generations. How does a young high school girl in the 1980s connect with this myth? Chaya Feldman is a character in the novel but she is also a dark ghost in Chava’s brain.

The line between Chaya who is held captive in a room with her friends and Chaya who is a captive in Chava’s head is blurry. It was clear to me that I had to personify Chaya Feldman. That’s why the educational tale works so well, because of the image of these young girls and the Nazis outside the door. I couldn’t keep it far away, as a distant story, I had to give her a voice. In literature, the reader becomes a witness, and I wanted the reader to witness what happened in that room. And as a writer I felt a dark passion to be in that room, to be Chaya Feldman, to write her.

There was one scene written in Feldman’s voice that I felt conflicted about. Initially, I thought the Nazis would always stay outside of the room, on the other side of the door. This is how Chaya Feldman describes it in the original will, and in the story I was told, the Nazis are always outside the room, they never enter. But in the novel, I wrote a scene where Chaya dreams of a Nazi soldier, and she is even attracted to him. A lot of readers reacted to that. Some of them wrote or emailed to say how horrified they were by the idea that Chaya would feel desire, even for a moment, for this Nazi soldier. This is my darkest side, I never planned on writing it, I thought the Nazis would stay on the other side of the door, like in the original story, but then somehow, I wrote it, and I turned it into a dream to make it more subtle. I included in that scene the darkest legends: the Nazi soldier tells her he heard about a non-Jewish man who was caught inside a Jewish woman’s body (while sexually assaulting her) and he cut her open to free himself. These are stories that we talked about during recess in school, among the students, not in the classroom. It was a way to speak about sexuality. I just turned fifty, so I am talking about thirty-five years ago in an all-girls high school in Bnei Brak, there was no other way, a sublimation, to talk about sexuality. It is an educational sublimation to talk about sexuality–the Nazi soldier wanted to do things to the girls–it was a mixture of darkness, education, and sexual thrill. I put it in the book: it is a story about sex and death, where sex equals death.

Miriam: And passion, sex that is the result of passion, the girls that are murdered (spoiler alert) are those who allow themselves to succumb to passion.

Sarah: It’s similar to the trope in American horror films, the girl who is not a virgin dies first, and the virgin somehow survives. It wasn’t a conscious decision I made, my unconscious played a role here. And it shows the similarity between the girls of the ulpana and those American high schoolers.

My editor had a brilliant idea that I did not include in the book: the punishment should be that one of the girls would find the myth of the ninety-three so compelling that she will commit suicide, to become Chaya Feldman. Something very dark and correct, I did not write it, but I think it is important to address it; when you educate girls on these dark myths, there can be a dark price to pay for this type of education.

Miriam: this idea exists in the novel more subtly: in a conversation between Chava and her best friend Riki, Chava expresses doubt about whether every one of the ninety-three chose to commit suicide, and reminds Riki of the time they played a game as six-year-old girls, acting as two of the ninety-three girls, and Riki did not want to die. But Riki answers with conviction: “But I also remember what happened next […] I remember how you shoved your fingers in my mouth and made me, and till this day I thank you for it. Thank you for killing me back then”. It’s such a strong moment. One of them has doubts, but her friend insists that their way is correct, the only right way, and that she would have done the same today.

Sarah: That’s true, I forgot that moment, and Riki often personifies the voice of the educator.

Miriam: And this dynamic is repeated with Chaya Feldman and her friend Ruthke in the play and in her diary chapters.

Sarah: Well, Ruthke is an imagined character I invented. In both cases it is the golem that turns on his creator; Riki or Ruthke are more righteous or pious than Chava and Chaya.

I planned that Chaya would not want to die and that the others would force her to die. While I was writing this scene, I had the idea that these women who forced her to swallow the poison would decide to sign the letter, the will, in her name. Chaya Feldman was an idea, a muse, I felt like she guided my hand and pointed me in that direction.

Miriam: Going back to the play the girls are trying to produce in the novel – תשעים ושלוש בנות הגאווה – is that a real play?

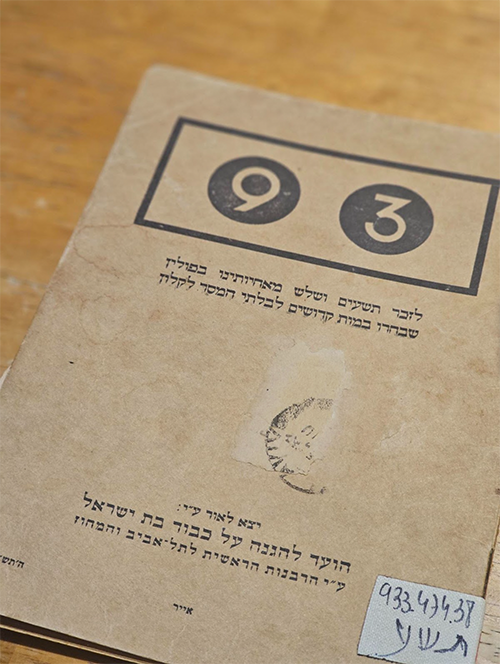

Sarah: No, but it is based on an old booklet. The title בנות הגאווה is from there. It was a booklet by “The Committee for the Protection of The Dignity of the Jewish Girl” published in 1943. It is a small booklet, about fifty pages, telling this story. I found it on a bench in Bnei Brak, while I was working on the novel, I had about a quarter of the book done, and I couldn’t believe it. Some things in writing are just unexplained coincidences. So, this play was not real, but it is based on these types of memorial texts.

Moreover, I was always a performer, I was an actress, I had a one-woman show in 2014, and already in high school I was the actress and the head playright. And in high school we put on a lot of shows. It was artistic sublimation, this was the permissible form of expression, and we were girls who played all the female and male roles. I was always the lead actress and the writer of these plays. In high school it was freer, and we put on a lot of comedy shows. But in elementary school we put on a lot of educational plays, for example an adaptation of “Dot and Anton” by Erich Kästner.

For example, I remember a play we put on at the end of eighth grade, where I played a mother, and my friend played the father, and we had a very sick kid. I was crying, and the father went to the Western Wall to pray, and when he came back home, I ran to him and cried “Shimon, Shimon, the child is healthy”. And I remember this anecdote because there was an obvious gap between our faith in these educational tales and our parents’ cynicism. It was one of the only shows that was open to parents, usually shows were just for the other girls in school. When we rehearsed the play it felt so very touching. But when we performed this play in front of the parents, as I was running to the husband, at the emotional peak of the play, the audience laughed, and the parents laughed. I felt insulted. But as a grown-up, I feel that this gap between what we were taught and how cynical the parents felt about those values is unbearable, and I cannot forget it, it just stuck with me. We were told to internalize and perform this type of story; but when we showed this to our parents, they all laughed.

Miriam: It almost feels like hypocrisy in those impossible educational values that the parents cannot live up to, or not necessarily believe in wholeheartedly.

Sarah: I think of it as duality (not hypocrisy).

Miriam: Yes, duality is more subtle. And this duality also exists in your novel, which offers a sharp criticism of those impossible ideals. These impossible standards that no one can live up to. And who wants to live up to that? Who wants to commit suicide?

Sarah: Yes. A character like Michal Levin is the embodiment of that idea, and she asks this question. And I think most of us would not choose suicide. But there was this coating on our education. I chose this age, sixteen or seventeen because it is the age of sexual awakening. And this sexual awakening in this Orthodox environment is happening despite these tales we were told, despite the strict education. The first buds of sexuality are very powerful because they put educational values into question.

The novel opens with Chava running and worrying that the slit in her skirt will tear. And I must say, this novel is based on the reality of my adolescent years. Of course, names were changed, but we did have a teacher who oversaw students’ modesty, and there were regulations regarding the length of the slit on the skirt, it was not to exceed five centimeters above the knees, and they would measure it. So we walked around with safety pins because the slit would tear when we ran, which is also metaphorical – you are not allowed to widen your strides. We would fix our skirts in the bathroom with safety pins. This scene in the novel with Chava and Michal is based on that. The friend will sew the slit closed for you. A slit was also a nickname for the women’s genitals, so there is this metaphorical layer of closing the slit and securing it, and that is done by another girl. And that’s another point – sexuality is enforced by other women, not by men: the teachers in charge of modesty, Miss Luria the vice-principal, and the Rikis (the modest friends). And there is a difference between the young girls who police each other and the older women who might also have some dark jealousy of the younger sexual women.

Miriam: The “modesty vampires” that you describe in the novel, that’s very dark. These are older women who roam the streets and scold young women who are not modest enough.

Sarah: Yes, and that’s also based on real ladies who used to walk around Bnei Brak. I didn’t invent anything. I remember one woman who would walk around the city and scold us for not being modest enough and order us to button up our shirts and things of that sort. And once, when I was on my way to synagogue on Rosh Hashana or Yom Kippur she saw me and yelled at me that my prayers are worthless because of the size of my cleavage. I felt so insulted, and that was the basis of my confusion between the goals and the means. Because the goal is presumably to get closer to God, but you get yelled at because of something superficial and external. This obsession with the external, with appearance, makes you forget the essence.

I also included it in the scene of the cantor-in-training. I was a cantor myself in school, and when I was on stage I didn’t even pray, because I was so busy leading the prayer. I tried to count to see how much time passed, to know when I should pray again out loud, but I lost my own prayer.

Miriam: And you were left with the performance of prayer.

Sarah: Exactly. And the system encourages it. The educational system focuses on the outside, the length of your sleeve, and not on the inside, the faith. When I was in high school, I wasn’t really strong in my faith. I was very orthodox, I excelled in Orthodox practices, but I didn’t believe in God. Today I believe, I am not going to elaborate on what practices I keep or not, but I believe in God, and back then, when I kept everything, I did not believe at all.

Miriam: So considering this novel is based on real things you have experienced, I wanted to ask about Ganzach of Jewish Resistance גנזך העמידה היהודית, the little independent Holocaust Museum in Bnei Brak that Chava’s aunt Minda is running in the novel. Is that a real place?

Sarah: No. There was a Ganzach Kiddush Hashem but it was not active. I based this institution on a similar place in Jerusalem, Chamber of the Holocaust, which haunted young Orthodox people. They had pornographic sorts of items – a Torah scroll made out of skin, soap that you were told was made out of Jewish fat, a bag of Jews’ ashes, and shoes. This place appeared in our nightmares. But again, it was a horror combined with forbidden excitement. That was our horror film.

Miriam: Interestingly, it’s so close to Yad Vashem, but the school chose to take you there instead.

Sarah: It is like the dark twin of Yad Vashem.

Miriam: And where is the Holocaust institute you worked for in Haifa located on this scale between Yad Vashem and the Chamber of the Holocaust?

Sarah: The institute was not a museum; it was focused on education on different subjects in Holocaust studies. We had five units of lectures and seminars for groups. I lectured mostly about Nazism and propaganda. Back then I personally liked to shock my listeners. Today I don’t do that. I wasn’t the regular type of educator there; the Institute’s official line was very conservative and reliable and I tended to push the boundaries.

Miriam: In the context of the myth of ninety-three it seems to me that the places that kept these types of myths alive are these institutes that focused on the extreme type of stories. I never visited a museum like that.

Sarah: I am not sure if it is active today. But in the 1980s and 1990s, it featured prominently in many nightmares of young people drawn to its grotesque appeal.

Miriam: The stories of Chaya and Chava mirror each other, and images from the past narrative leak into the current one. Even the phonetic similarity between their name Chava and Chaya brings the two together. And one of the strongest connections that weave through their stories is the ominous key phrase “keep your panties safe”.

Sarah: I think it is a reflection of the idea that we were all educated in the same way. And that is why the novel works, the educational message remains the same, they just get a new expression. As a child, I remember when I was swinging, I was told not to spread my legs, so my underpants won’t show, and I didn’t understand why. I played with that sentiment with the phrase “keep your panties safe” because it adds a layer of sexual meaning. It echoes other expressions, such as “he wants to get in your pants” and other expressions of that sort. And in the story Chava’s mother did not keep her panties safe, she loses her panties, and she is punished, and she dies. And Michal Levin, one generation after Chava’s mother, did not guard her panties, she let someone in, and she dies as well. Again we see this equation: sex equals death. Although in the story of the ninety-three keeping your virginity or purity also equals death. So, what is the right way?

Miriam: And what is the value of one’s life without one’s purity?

Sarah: You’re not worth anything without your purity, you are almost not Jewish. You become the enemy of Chaya Feldman, and who is her enemy? Who is waiting outside of the door?

Miriam: You’re crossing to the other side, to the soldiers. If you don’t choose to stay with Chaya Feldman and the rest of the good girls.

Sarah: Maybe you yourself are the soldier. These are the messages that are taught to young women in this society.

Miriam: And the title of the novel reflects that result, being the exemplary, well-educated girls.

Sarah: The title “Well-Educated Girls” (in Hebrew: נערות למופת) was also a sort of a play on the Hebrew title to the popular children’s book Les petites filles modèles (in English: Good Little Girls, in Hebrew:ילדות למופת ) by the Countess of Ségur. She was very Christian, and her popular books had Christian values in them, but we didn’t know that and we read her books as children. When I grew up I realized how similar those messages were, whether Christian or Jewish: “Be a good girl. Listen to your mother. Be nice”.

Miriam: I thought it was interesting that the title in Hebrew was not “Good Girls” because that is the expression that comes back again and again in the novel. Be a good girl.

Sarah: Yes, that is also a great title. But the word מופת mofet in Hebrew has the meaning of exemplary, these girls are the model for us.

Miriam: And it adds the idea of memorialization and perpetuation of the ninety-three. We all need to be good girls, and the ninety-three are the model.

Sarah: And it’s a timeless subject. It’s always relevant.

Miriam: More than ten years after the book was published, do you feel like you have a new perspective? Something you would add or change?

Sarah: No, I stand behind every word. I do think that today we know better how fake the story of the ninety-three is, we don’t trust this narrative. And in the world today where we hear about “fake news” all the time, this was maybe the first big fake news story that caught on. It is a successful fake news story. Today it’s much harder to create this type of story.

Yet, educationally I think nothing changed, girls are taught the same tales in different versions, retelling the same narratives. In the end, the same message comes through: “Be good girls, and keep your panties safe”.