Pesya Shereshevski’s name is not widely remembered now, but after she arrived in the Land of Israel in 1945, as one of the first Holocaust survivors to reach Palestine, she was famous as a gifted public speaker and powerful writer who reached audiences of all varieties. She was also one of the rare women who served alongside many male administrators in the highest rungs of the Bais Yaakov movement. Within the Orthodox world, she was known as “the mother of the refugee girls,” for her work running a home for such displaced and orphaned girls and young women in B’nei Brak. But she also reached beyond it, becoming a symbol of spiritual heroism during the Holocaust. As a speaker and writer, she transcended the boundaries of her gender and community. Hatsofeh, the Orthodox Tel Aviv daily, described Shereshevski as “a unifying symbol of the Jewish people as a whole.”

Pesya Shereshevski was born in the small city of Ostrolenka in 1918, the youngest of a family of Gerer Hasidim; she studied in the Krakow Seminary, and was active in Bnos Agudath Israel. Her Bais Yaakov education included Hebrew, Polish, and German language study. Her first teaching position, at seventeen, was in the village of Kinice, Poland. Her older sister, Basya Leah Hirshkovitz, who was among Sarah Schenirer’s best-known students, was a founder of a Bais Yaakov in Warsaw and one in Chelm. Her other siblings were murdered in the Holocaust. Pesya married Meir Shereshevski, a student of the prominent rabbi and Agudah leader Rav Elchonon Wasserman, at the beginning of the war. Shereshevski was the secretary of the Executive Council of Torah Sages of Warsaw. The family was deported from the Warsaw Ghetto in 1943 to Maidanek and then Auschwitz. Many other camp inmates remember Pesya as having maintained her humanity and whatever she could of religious observance in the camps. In 1945 she was moved to Mauthausen and then Lenzing, which was liberated by the Americans on May 5, 1945. She made her way to a Displaced Persons camp in Italy, establishing a Bnos Agudath Israel kibbutz there. It was in this camp that she met some soldiers of the Jewish Brigade, who made an impression on her; she sought their help in bring as many refugees as possible to Palestine. At this camp, Pesya also met Binyomin Mintz, head of Poalei Agudath Israel, and Hizkiyahu Yosef Mishkovski. After a brief stay there, she immigrated to the Land of Israel on October 26, 1945. She is one of those who arrived in the first postwar wave of immigration, which included Zionist fighters and partisans. She was a widow, suffering from the loss of her child and major health ailments–including blindness in one eye. Nevertheless, she made a name for herself from her earliest days in the Land of Israel with her powerful public lectures, most of them to secular audiences, delivered in perfect Hebrew. In these talks at Habima and elsewhere, she spoke from a unique perspective that combined Orthodoxy and Zionism, Jews in the Land of Israel and those who had suffered in Europe. She often spoke of religious life, and about its destruction during the Holocaust. In contrast with other survivors and partisans in the public sphere after the war, she stressed the spiritual resistance of Orthodox women and the roles they played as nurses, guides, and spiritual leaders in the ghettos and camps. She spoke movingly about how women had suffered doubly in the camps, humiliated as both Jews and as women. Whatever the talk, her message was always the same: we must bring these refugees to the Land of Israel. As she wrote:

There were those who fought with their children over bread crumbs. There were those who wished to save themselves by sending their children to the crematoria. There were those who sold their bodies for the smallest advantage. But these were the minority. Most women were strong. They maintained their purity, they didn’t abandon the laws of kashrut, even when this hastened their deaths.

As Michal Shaul points out, Pesya Shereshevski focused on the distinctive experiences of women in the Holocaust, but she also spoke of women’s commitment to Judaism more generally, as in their adherence to laws of kashrut under extreme circumstances.

Pesya Shereshevski maintained a wide circle of acquaintances and colleagues. Among her first visits in Palestine was to Moshe Chayim Okun, an Agudah activist who was close to the Chazon Ish (Avraham Yeshaya Korelitz), whom she also met. But she was not reticent about her enthusiasm for the Zionist paramilitary organization the Haganah, something that disturbed the Chazon Ish. She had close relationships with many secular Zionists, including the Labor Party politician Yosef Bratz; she accepted an invitation from him to spend a Sabbath at Kibbutz Deganya, where she spoke with kibbutz members at the Shabbat gathering about her experiences in the extermination camp. Bratz delivered one of the eulogies at her funeral.

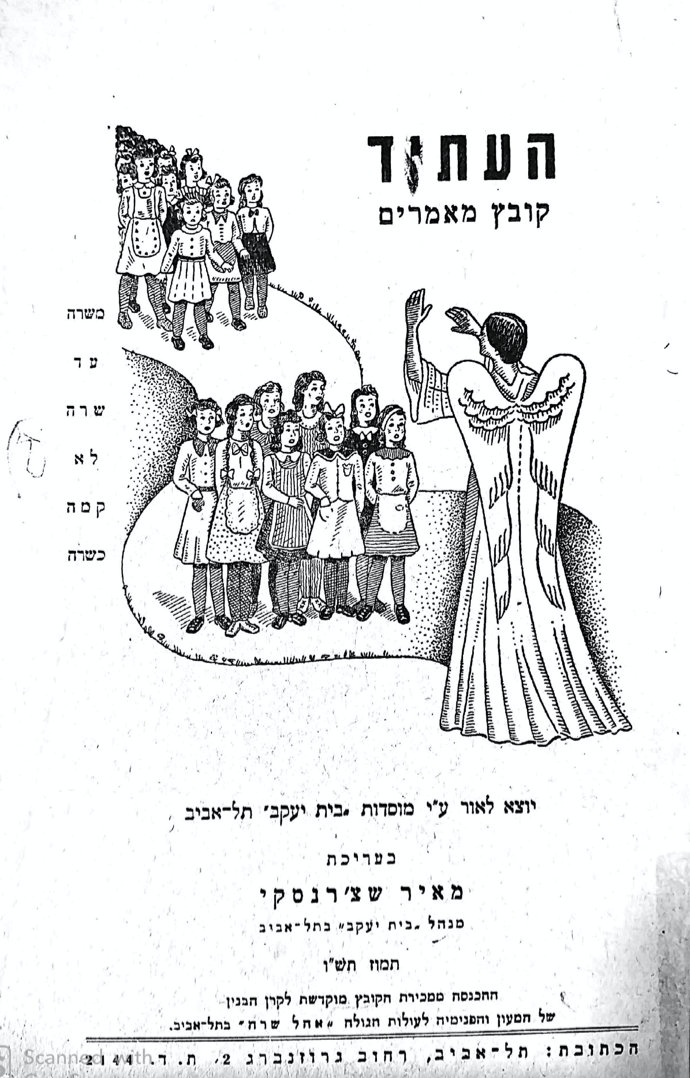

In 1946, when the Chazon Ish helped establish an orphanage in Bnei Berak for girls who had survived the Holocaust (called Ohel Sarah), he invited Shereshevski to administer it along with his sisters, Tzviya Greinman and Miriam Kaniyevsky. Her ill health, however, kept her from this work at the orphanage, and while she recuperated in Safed, her friend Sarah Dessler was acting manager. A woman interviewed by Michal Shaul described her first meeting with Pesya, when she was a lonely young widow:

The “Mother of the Refugee Girls” would not talk with me until I had eaten something. “I don’t enjoy conversing with hungry people,” she used to say, quoting the rabbinic saying: “The words of the sages are heard with pleasure.” I really wanted to eat, because I haven’t eaten for sixteen hours, so I didn’t say no. After I had eaten, and we had had a long conversation, I came to live at the “Sarah Schenirer” institution.

Rejecting many illustrious matches, Schereshevski remarried a man, Chaim Yazin, about whom little is known beyond that he attended the Slobodka yeshiva in Bnei Brak; this marriage was childless. She died after a long illness on January 2, 1956.

- This blog and biography is drawn from Michal Shaul: Pesya Shereshevski – A Haredi Survivor who Broke the Borders of Gender and Sector, Israel 18 (2011), pp. 131-155 [in Hebrew].

- The photos are taken from Michal Shaul: Holocaust Memory in Ultraorthodox Society in Israel. Indiana University Press. (2020)