We take a break from Naomi’s series interpreting class pictures, in part due to the disruption that COVID-19 has caused to our daily and weekly schedules. Instead, in a timely post, we are highlighting a haggadah this week.

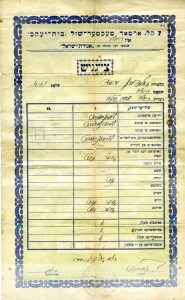

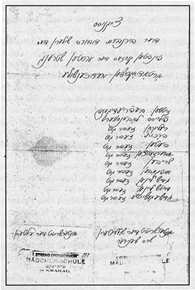

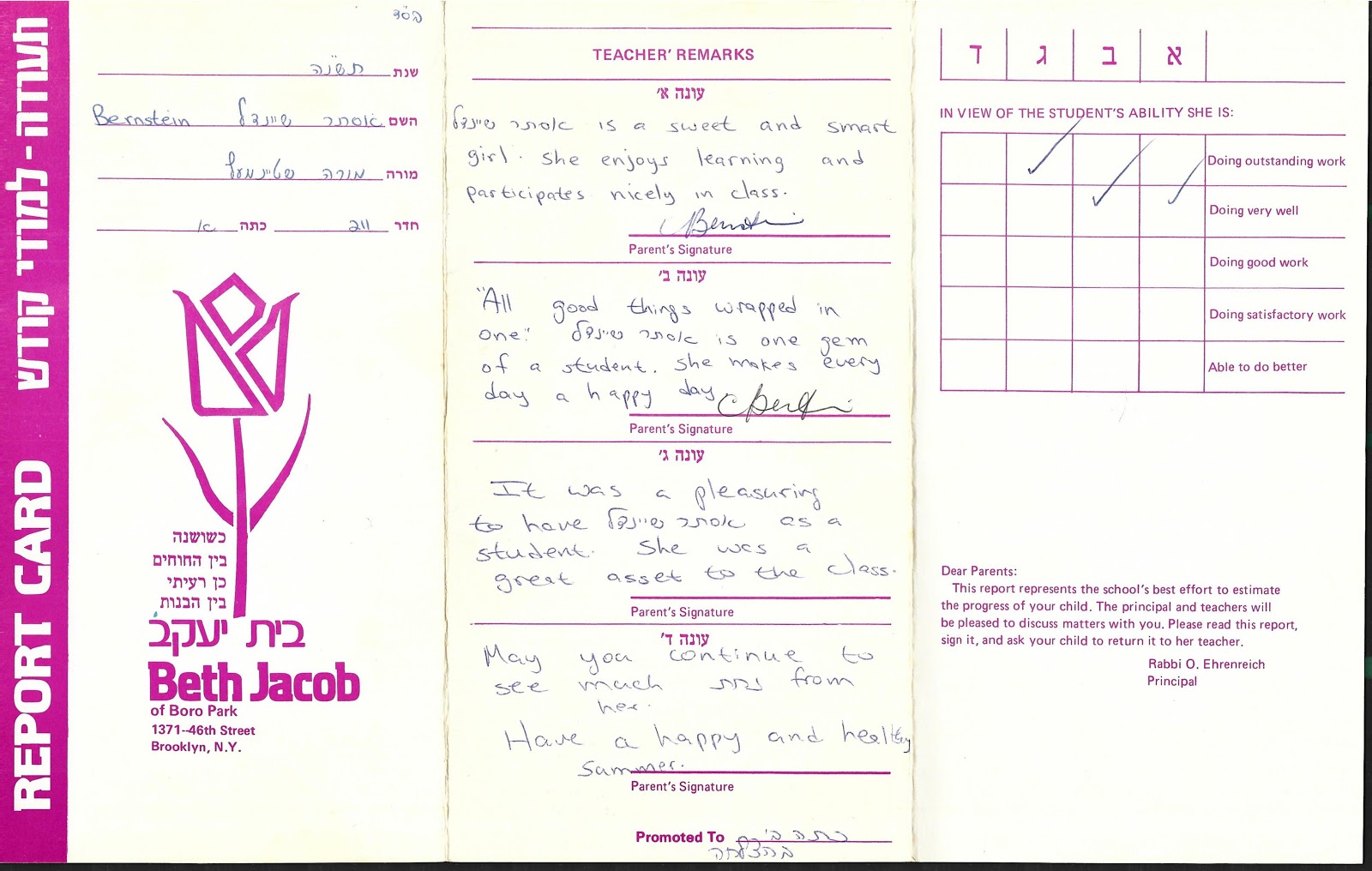

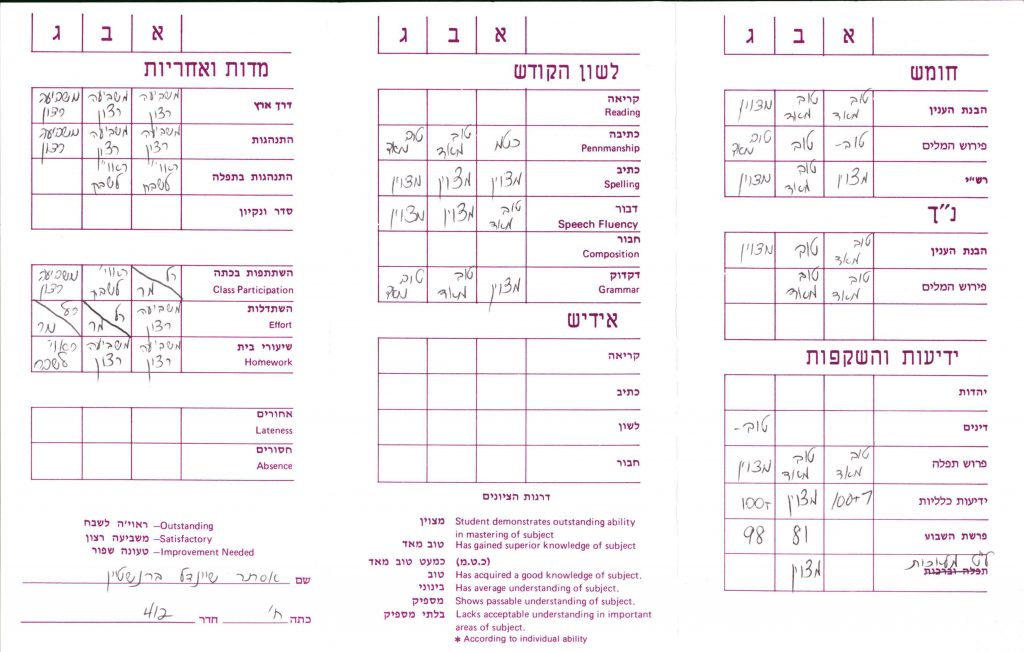

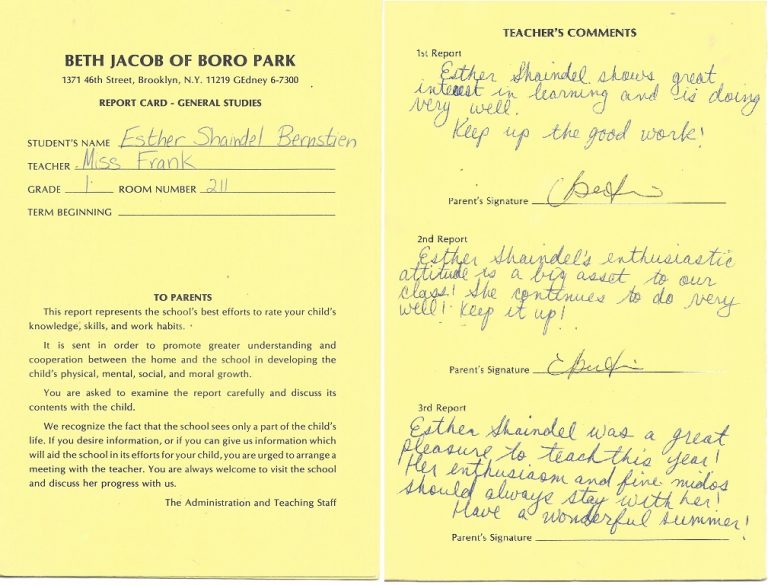

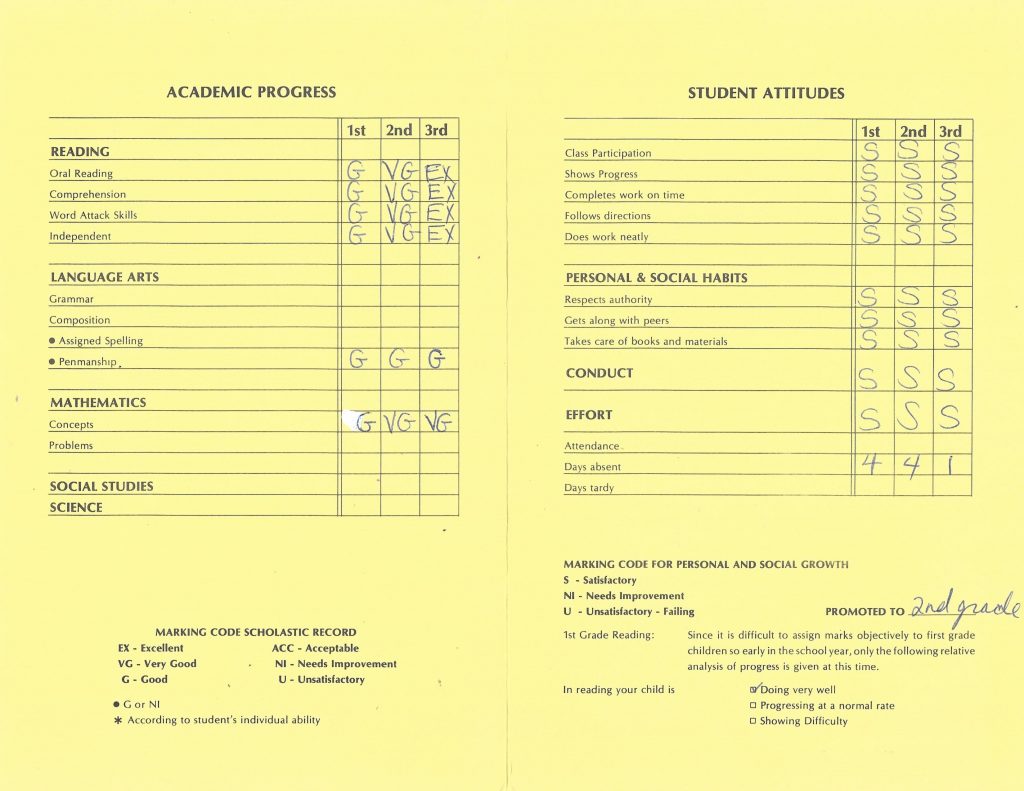

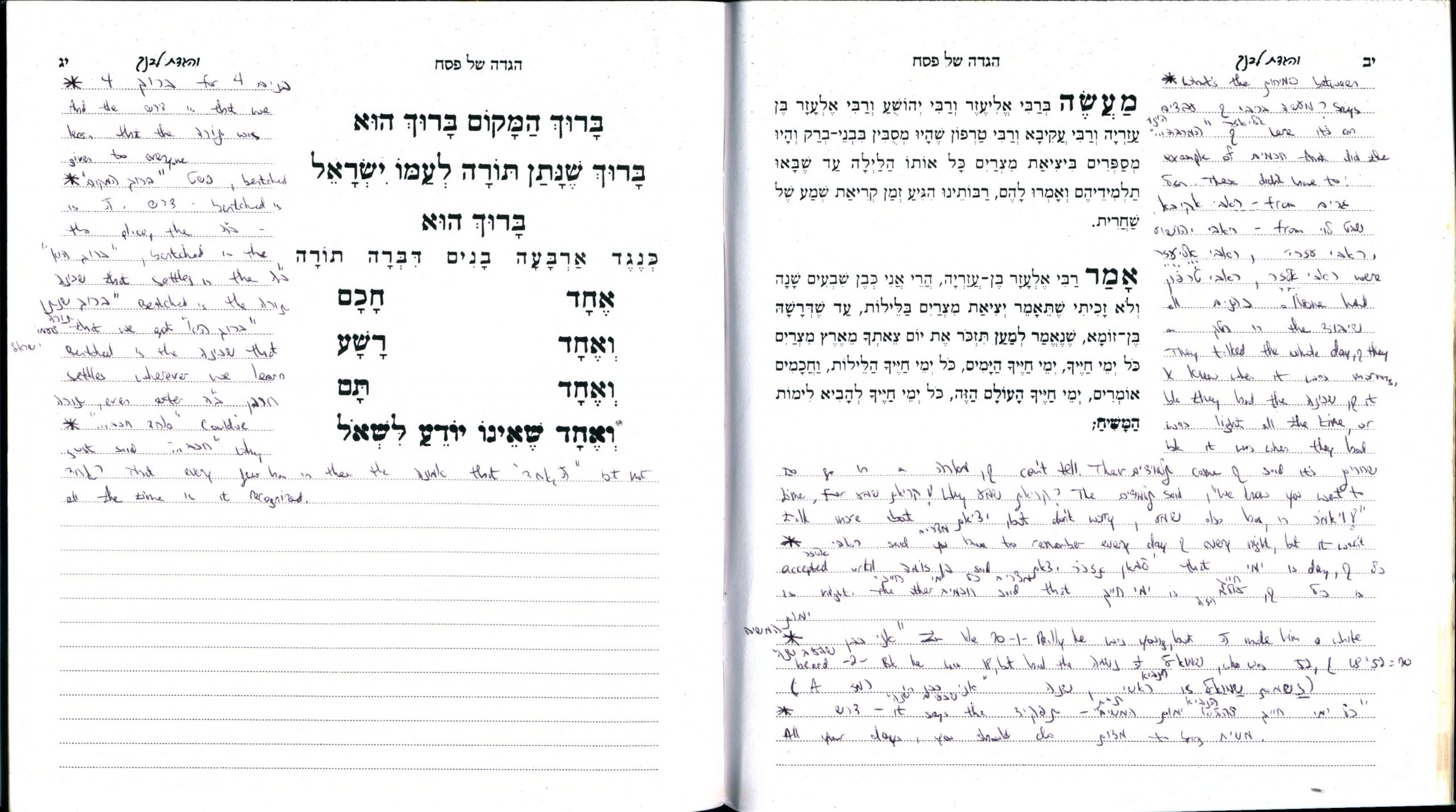

This haggadah comes to our collection from Mindy (Friedlander) Schaper. It is typical of texts used in grades 6-8 in Bais Yaakov schools, with lined spaces surrounding the text of the haggadah itself, allowing students to write notes directly into the text.

(Haggadahs from younger grades tend to be handmade collections of paper tied into a booklet, featuring such fun additions as a cutting of a towel to decorate the page for urchatz and rachtzah. We hope to share more of those in future weeks or years – perhaps in time for Pesach 2021!)

Much can be said about the practice of using haggadahs with spaces intended for note-taking. While students are expected to take notes during classes on Chumash, Navi, Halacha, etc., they are not expected to write in the seforim themselves. However, haggadahs are meant to be used during the seder, not merely studied and then stored away. The space for notes is indicative of the text’s intended use: as a discussion aid during the seder.

The format of some of the notations is indicative of the intended use as well. Many of the notes begin with a question, mimicking the structure of the haggadah itself, which begins with four questions and then goes on to answer them by telling the story of the Exodus.

The fascinating result of this practice is that girls in Bais Yaakov engage with the text more intimately than they do during the rest of the year. In notes for other classes (coming soon to our online archive), we can see a similar format of question-and-answer, usually quoting a meforash like Rashi or Rambam. Here, though., the girls get to take ownership of the text in a more personal way, by inscribing their own words (albeit still the thoughts of others) directly onto the page in a layout that echoes Talmudic commentary.

A feature that I find particularly intriguing is the grade and comment on the title page. Someone, presumably the teacher, has graded the haggadah with an Aleph+ with an accompanying comment of “excellent work,” followed by the traditional Pesach wish for “next year in Jerusalem.” What was being graded? The commentary, which almost certainly was not student-created but dictated by the teacher? The handwriting? The amount of notes written? Did the students perhaps do research to write their own notes, rather than having the teacher dictate the notes?

Of course, we can simply ask Mindy these questions and rely on oral history since this haggadah was annotated so recently. But these questions apply to a broader range of class notes and texts and are worth asking and tracking through Bais Yaakov’s history from Europe through to contemporary schools in America, Israel, and other locations.

As we head into a seder unlike any other most of us have experienced, with fewer people at the table and perhaps no children or grandchildren to ask the Mah Nishtanah, we wish you all a safe, healthy, and happy Pesach.