Among the more unusual chapters in the international history of the Bais Yaakov movement is the founding of a Bais Yaakov school in Shanghai, China. Shanghai had a small Jewish community since the nineteenth century, supported by such wealthy Iraqi-Jewish families as the Sassoons and the Kadoories, but this community swelled in the early 1940s with the arrival of many thousands of Jewish refugees from war-torn Europe—Shanghai was among the few places that did not require a visa for entry. Among these refugees (estimated to number 16,000-30,000) was a group of around 400 students and faculty of the Mirrer Yeshiva, many from the Yeshivat Chachmei Lublin, along with others from different yeshivas, who had received transit visas from the Japanese diplomat in Lithuania Chiune Sugihara (1900-1986). They escaped first to Kobe, Japan, and then to Shanghai, where the Mirrer Yeshiva reestablished themselves in the Beth Aharon synagogue. The group was supported by the existing Jewish community, an American committee that provided financial support for the Mirrer Yeshiva, the Va’ad Hatzalah (Rescue Committee), the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), and the American Joint Distribution Committee (AJDC), whose Shanghai office was led by the social worker Laura Margolis (1903-1997), the first woman to serve as overseas director of a JDC office. From 1941 to 1945, the Jewish community was restricted by the Japanese authorities to the Shanghai Ghetto (a ghetto without walls), formally known as the Restricted Sector for Stateless Refugees, in the Hongkew district of the city.

Among the refugees were a few Bais Yaakov teachers who had taught in the interwar schools. These women founded a Bais Yaakov in Shanghai, which was run as an Orthodox girls school but provided a Jewish education to orthodox and secular refugee girls alike. While the story of Mir in Shanghai is fairly well known, the story of Bais Yaakov in that community is much less studied, scattered in the archives and remembered mostly in family lore. Who were these teachers, and what were their relationships with refugees from the yeshivas? How did they receive their transit visas? What were their experiences in this environment, and how did they find teaching materials? How did they see the Bais Yaakov of Shanghai within the larger story of Bais Yaakov history? How did they remember this past in the years that followed, after they emigrated again to the United States, Israel, Australia or elsewhere? A few people were especially important in providing information about the Bais Yaakov in Shanghai: Judith Cohn’s card, photo album, and autograph book (autograph books were popular in Bais Yaakov from the beginning until today) are available at the Amud Aish Memorial Museum in Brooklyn. Charlotte Wendel’s interview with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum can be heard in this link. Devorah Epelgrad Cohn supplies some information about how Bais Yaakov students found yeshiva students to add them to their visas, not always with success. And Chana Persoff, whose mother taught at Bais Yaakov in Shanghai, contacted the Bais Yaakov Project and contributed the richest trove on this chapter. She gave us a photo with over a hundred students and teachers, another detailing the names of many more students and teachers, including a few who were prominent in Orthodox post-Holocaust life in the United States and Israel.

Though the school was orthodox, many students were from secular German Jewish families who found refuge in Shanghai. The school provided a hot, meaty lunch to all students, which was an attractive reason to send children there. This might explain the short sleeve and skirts seen in the school picture.

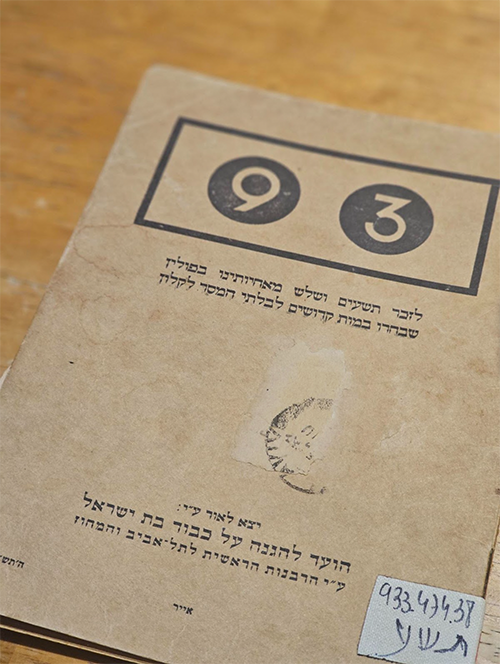

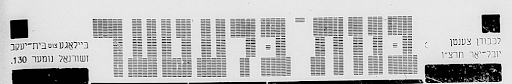

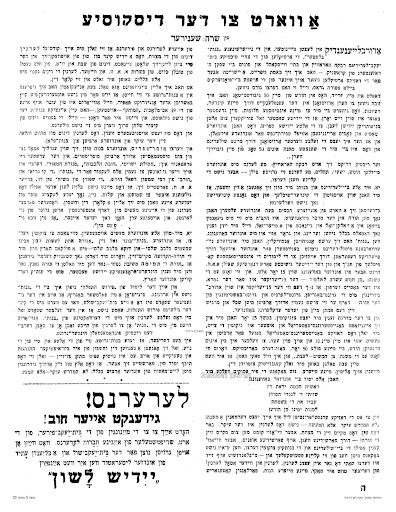

We were also fascinated to see an article from 1941 by Basya Mlyarcewicz, who had taught in a Bais Yaakov in Kamenetz, Lithuania, before finding herself on the “hard Shanghai soil.” The article was published in the Shanghai Yiddish periodical “The Jewish Voice from the Far East,” and it described the origins of Bais Yaakov and linked the present Shanghai school with this past.

In upcoming blogs, we hope to collect more information on this school from these sources, and also “read” the two photographs we have of the school, the first from 1943, and the second from 1947. What accounts for the differences between these photos, including the number of students included, and the way these students are dressed? What else can we glean from these sources? And how did Bais Yaakov of Shanghai view itself—at least for one teacher whose writings have survived—in relation to the origins of the movement, which also were grounded in the dislocations of the refugee experience?

We also have some testimony from descendants of these exiles. Chana Persoff, Basya Mlynarcewicz’s daughter, writes:

My parents escaped together (not yet married) from Poland to Vilna. My mother was a Bais Yaakov teacher in Kaminitz. My mother went to the Bais Yaakov in Ostrolenka where she was born.

My father knew my mother’s brothers and that is how they came to escape together.

My mother arrived in Shanghai in 1940. Later on, many of her friends, who were also Bais Yaakov teachers, arrived.

In October 1941 my mother wrote a letter (attached in Yiddish) on the front page of the Yidishe shtime proclaiming that “we, the children of Sara Schenirer,” have to start a Bais Yaakov. And so my mother and her friends started a Bais Yaakov.

My father, Yitzchak Shafran, married Basya in Shanghai in 1942. Shafran also taught in Shanghai, teaching older girls who often took secular classes in the morning and studied Judaism with him in the afternoons.

In 1943, a beautiful picture was taken of the school which by then had about 150 students (see attached). The woman in the center (with the hat) is my mother. Many of the students were children of the German Jewish refugees who had also escaped to Shanghai.

While they were in Shanghai they were in touch with Rebbetzin Kaplan in America asking for monetary help.

Rabbi Hellman, who later became my principal in Bais Yaakov, was also in Shanghai and married Bluma, a friend of my mother.

This Bais Yaakov in Shanghai proved what Sara Schenirer instilled in her students that wherever you are a Bais Yaakov should be established.

May this school (established during the war) be a blessing to Sara Schenirer’s memory.

All the best, Chana

P.S. In the Ostrolenka picture (below), my mother is in the top row, extreme left.