Translated from the Hebrew by Miriam Schwartz

1.

Krakow, August 1942

How itchy this nightgown is.

It’s too big on me and it’s made of stiff lace that chafes my skin. My skin, in the most sensitive areas, is rubbed raw, as irritated and pink as raw meat.

It’s not a new nightgown. It’s white, with a light blue tint, and it seems like it’s been washed at least once. My mom would call the faint scent coming off it “slutty”, but I actually like it. I try not to think about whoever wore this nightgown before me, but I can’t help myself.

The itchiness won’t stop bothering me, my fingers keep tugging at the lace collar, trying to pull it away from my skin. My fingers feel damp, but I’m not sure with what. Blood? Did I scratch myself that hard? Have I already lost the ability to recognize the borders of my own body?

At least my nightgown isn’t too tight. They gave poor Ruthke such a small nightgown that her body is bursting out of the muslin. I try not to glance in her direction, even by accident.

She sits on the bed across from mine, flushed all over. Her skinny arms cover the open neckline, as if she were trying to soothe her exposed, humiliated flesh. Her lips move as in prayer.

“Soldiers,” they said. Lots of soldiers, in uniform, laughing loudly.

And then we understood the meaning of the fragrant nightgowns, the warm bath, and the beautiful beds in the big, illuminated hall, after we had been held in that dark cellar for two weeks. Only then did we understand what was expected of us, only then did we understand that. . .

But I was suspicious of the soft bed from the first moment. The white pillow was greasy and smelled of men.

Ruthke is weeping out loud now. She trembles and sobs on the floor. Her pale skin glistens under the harsh overhead lights.

Why do they keep the big hall so brightly lit? What are they planning? Tobi and Rivi pray beside me in frantic whispers. Until the day we were caught, these two were mortal enemies who argued during every recess, and whose feud divided the class into two rival camps (as always, only I didn’t know where I belonged). Look at them now: they cannot be separated, in the future people will say about them “neither in life nor in death”.

In the future people will say many things.

We don’t seem to have done anything in the past two weeks but cry and pray. What more can we do before the soldiers come? Will they be in uniform? Will they have greasy hair? Will it be the ones we heard, laughing out loud?

I’m tired of tears. They’re pointless, and unlike the other girls, I don’t sit and think about home.

Not only do these memories bring me no comfort, they magnify the pain, since who knows what happened to Mama, to little Chaim and the rest of them. . . I command myself not to remember, and the memories fade and disappear into the loud rumble of my brain.

But there is one insistent memory that returns and will not leave.

I am about four years old, walking with Mama to the park. A strong wind is blowing and the trees rustle. Laughing, frozen, I run into the wind, and my skirt lifts up and balloons around me and it seems like I might be blown into the air. My mother smiles at me and says, “Chayale, you’re a big girl already, you have to be careful not to let your panties show”.

Mama, I’m not wearing underpants now.

2.

“Once upon a time, there were ninety-three girls,

Innocent and pure.

They chose to end their lives,

Instead of living like swine”

(Unknown source)

Run, run, or you’ll be late!

I run quickly, jumping over a mud puddle. My soft backpack bangs against my ribcage and my limbs flail in all directions. As late as I am, I keep my stride from growing too long, so the narrow slit at the back of my skirt doesn’t split open like the jaw of a hungry shark, something that’s happened to me more than once while I was running.

Out of the blue I remember the ethical tale about the Jewish daughter who was sentenced to be dragged through the city by racing horses, and the one thing she worried about in those last moments was how to keep her skirt from riding up her thighs.

I never accepted her wondrous solution, attaching the skirt to her flesh with iron pins. I imagine the sharp iron piercing the thin skin and shiver. I myself cannot bear the slightest pain (except for the pleasurable pain caused by tiny pinches of the fingertips), and I also cannot forget the facial expression of the teacher who told us this tale. For her, any other choice would be considered a complete educational failure.

Run, run, or you’ll be late!

The puddles shimmer on the broken pavement, the leaves glisten green, and the whole city seems to be opening itself up to whatever was coming. Bnei Brak turns beautiful in these surprise spring rainstorms that wash off the usual layer of dust. The other layers are harder to scrub away.

I breathe in the clean air and almost step on a startled cat with a truncated tail. Her small mouth opens to reveal a soft pink hole filled with teeth.

Not all cats manage to reach adulthood with their tails intact, and God help the stray dog that wanders into this area. I don’t know who is more terrified, the dogs or the residents of the city. It’s an old hatred, with roots somewhere in Europe. This city is completely free of dogs.

At least those who walk on all fours.

Run, run, or you’ll be late!

The exertion is taking a toll, and I feel myself bursting out in sweat. Damn it! Over the past few days I’ve given up completely on washing myself, satisfying myself, like any respectable French lady, by dabbing at the problematic body parts with a wet towel. I think I better slow down, even if that means I’ll be late. Better Mrs. Luria’s reprimands than the aristocratic all-smelling nose-twitching of Michal Levin.

I assume I’m not the only one in our class to take up this French method in the bathroom, but I’ve never openly discussed these habits with anyone. Strange, you can chat with your best friend about every subject under the sun, except for the number of times a week she showers. Just like the nose is one of the most sensitive parts of the body, so is smell one of the most sensitive topics of conversation.

I sniff at an armpit and my face twitches, damn it! I’ll have to rely on the fake politeness of my classmates.

Slowing down costs me dearly since there she is, already waiting for me by the gate, with her dead-blue laser eyes.

Mrs. Luria, the vice-principal, is all pumped up with the importance of her title, especially when she lies in wait for late students, and even more so when these are late students with potential, like me.

She looks like a volcano covered in a dress, with a wide stance that would look good on a town’s sheriff. Even the shiny gold Star of David brooch pinned to her blouse seems designed to intimidate. All that’s missing is the hat and the gun. Instead, she has a velvet baseball cap and she holds a thin leather notepad, as dangerous as any gun.

Boom! You’re dead. You lie there with dilated pupils, making sure, even in death, that the skirt doesn’t ride up above where Mrs. Luria thinks it should be.

“Good morning to you too, Miss Keller!”

Mrs. Luria’s gaze scans my washed-out jean skirt, hopefully examining the length of the skirt’s slit. Her tight lips show that she’s disappointed not to be able to find fault with it. According to Ms. Luria, each of us conceals a blushing, amorous Marilyn Monroe searching for a way out. Her role is to block that risk, forcefully if need be.

“What rosy cheeks you have this morning.” Her hand reaches out to my cheek, as if to give me an affectionate pinch, but actually to check for any damning trace of blush on her fingers. Again, disappointment.

“Oh… I ran the whole way, to get here in time,” I try.

“And yet you’re late.” She gives me a joyless smile, which scares me more than her usual frown.

What is about these teachers that terrorizes me so? What can they do to me? The embarrassing fact is that I’m always seeking their affection and approval. Any deviation from the rules threatens the loss of this love, and that’s what I’m afraid of.

But it’s even worse than that. I’ve let these feelings of dread grow to the point that I need to be liked by anyone in authority, no matter the cost. Waiters, cashiers, police officers, – anybody in a uniform evokes in me an immediate dread and the desire to appease them. Anybody, except for of course, Mommy and Daddy, or maybe I should call them by their proper names: Miriam and Avner.

“You have a lot of freedom these days”, says Mrs. Luria, “Getting out of classes for rehearsals, to work on… on this play of yours”, her lips tighten, “You wouldn’t want that to stop, would you?”.

Be quiet, lower your eyes, hold your breath, you’re standing under a giant house of cards that’s about to collapse on your head.

“And you know this is not a simple issue for us…” again those tight lips.

Keep quiet, Chava, just keep looking at her with your big innocent eyes.

“Well, I want you to come to my office after the morning prayer”, she says and starts down the hall. I stumble after her, aware that this is the first time she has mentioned the play. I think of saying something, but decide it’s better to keep my big stupid mouth shut, at least until I sit down in the prayer hall and let my heartbeat return to normal.

The prayer hall is known as “the cafeteria”. In the past, it served as part of a public kitchen, but today it only feeds our pure souls.

On stage, facing the dozens of praying girls, sits the prayer leader on duty. Today it is Osi, with her clever, sly tongue. I am just as good at flattery, but I hide it better. She’s mistaken in choosing to direct her flattery towards the teachers. She doesn’t realize, silly her, that if she is doomed to be a flatterer it would be smarter to direct her efforts at the students. The real power is in our hands, and always has been.

Ironically, the student prayer leaders aren’t the most devoted or pious students. On the contrary, the chosen ones are those blessed with dramatic reading abilities and nice voices, although these qualities often contradict silent, obedient piety. I should know. I’m not considered the best actress in the school for nothing. Leading prayers in the morning is part of my repertoire of performances, a bargain that works in my favor.

But on days when I’m the prayer leader on duty, I can’t actually pray. My entire being is concentrated on performing the role of a praying girl. My greatest fear is that I’ll mess up on the pace of the silent prayer, which the girls whisper to themselves. How long should I wait before I read aloud again from the prayer book? How long does it take to read four pages of Psalms? I stare at the girls to see when they raise their eyes from the prayer books, tock-tock-tock-tock, one by one they raise their eyes, like a row of bobo-dolls, and only then do I feel safe in continuing the reading. Of course, I make sure that throughout the wait my lips move continuously as if I were actually praying.

Riki once gave me a piece of useful advice “Why don’t you just pray? Instead of trying to figure out how long to wait just experience it yourself”.

“But how can I pray?” I wondered “I’m the prayer leader”.

Mrs. Luria stops me with a gesture of her hand.

“Don’t go into the prayer hall now”, she commands. “You’ll only disrupt the other girls. Go upstairs and pray in the classroom”. With a sense of relief, I walk toward the classroom, leaving the singing voices in the prayer hall behind. As always, they sound like the pure and innocent voices of a choir of altar boys, those who know no sin.

As usual, those voices reveal nothing.

If anyone can escape the all-seeing gaze of Mrs. Luria, it’s Michal Levin.

She leans against the bathroom door, taunting me with her impossible beauty, with her straight honey-colored hair, her bright lip-gloss-covered lips (I prefer a piece of margarine, which helps plump the lips, but Michal’s lips don’t need any help), the thin gold rings on her fingers. Her eternally white sneakers, and the two soft mounds that fill up her shirt in a distant and welcoming manner. I have no doubt she worked for hours to achieve this exact impression.

“So?” Michal looks at me “Why are you late?” and without waiting for an answer I don’t have time to invent she turns to Odelia who is beside her “Do you have a clue why she is late?”

Odelia, who reminds me of Napoleon, the giant pig from Animal Farm, is as cooperative as usual.

“Why is she late?” Even her voice sounds like a combination between a laugh and a snort, “Who knows what she did last night…” I sense the satisfaction in her little eyes and realize I have to get out of there.

“Got to run”, I say and turn away from them in wide strides.

Waaaaaammmmmm! The patient seams that hold the ends of the skirt’s slit together give up, and the shark’s jaw widens behind me with a tearing sound, as if at any moment it will bite my thigh.

7.

Krakow, August 1942

The nightgown doesn’t scratch anymore.

Maybe my skin is just getting used to the scratchy fabric sensation, or maybe it wasn’t the nightgown that caused the itching but the soap from the quick bath that was given to us in that big dark room.

When I held that square piece that was shoved in our hands, feeling its strange sticky texture, the soap barely foamed when it came in contact with the body, and my hands, which had already forgotten the feeling of soap, grasped it more forcefully.

Ruthke was standing next to me crying. “I’m so ashamed Chaya”.

At that moment I was ashamed too, and the heavy soap fell and was completely forgotten.

That’s it. Ruthke has lost her mind.

She squirms on the floor, mumbling and moaning. I can make out only one word, “soldiers”. Her face is covered with saliva, snot, and tears.

I try to keep my composure, to view it all thing from a distance, and what other choice did I have? The principal and Miss Hindy the teacher, disheveled and flushed, rush over to her and try to calm her, to raise her to a sitting position, but Ruthke continues to squirm on the ground. She looks like a large upside-down beetle. I can’t stop myself from imagining the huge shoe that will come and trample her body.

“There will be no soldiers, girl”, the principal says “They won’t be coming”.

In response Ruthke tries to bite her hand.

“No soldiers, Ruthke!” Hindy almost shouts the words. “No soldiers are coming in here!” I lean forward to see better and my gaze meets hers. My eyes are lowered first.

I can’t keep myself from wondering what Hindy knows about soldiers, how far she’s gone. In the past there were rumors that she was engaged to a young man from the city, who disappeared when the ghetto was established. Even before that she was quiet and closed off, and never talked about it. She always seemed to me too quiet and hesitant to be a teacher, but here, now, she raises her voice, perhaps for the first time in her life, trying to calm the hysterical Ruthke, or perhaps herself, but to no avail.

Because the truth that caused Ruthke to lose her mind, that will cause us all to do the desperate final act, the one you will cherish so deeply – that truth is already inside us.

It’s been lurking there from the moment we were born, germinating and developing on its own, red and hungry, feeding on the scraps left behind by generation upon generation of good girls who knew more than they should have, good girls who clenched sharp teeth, good girls who always did the right thing.

*

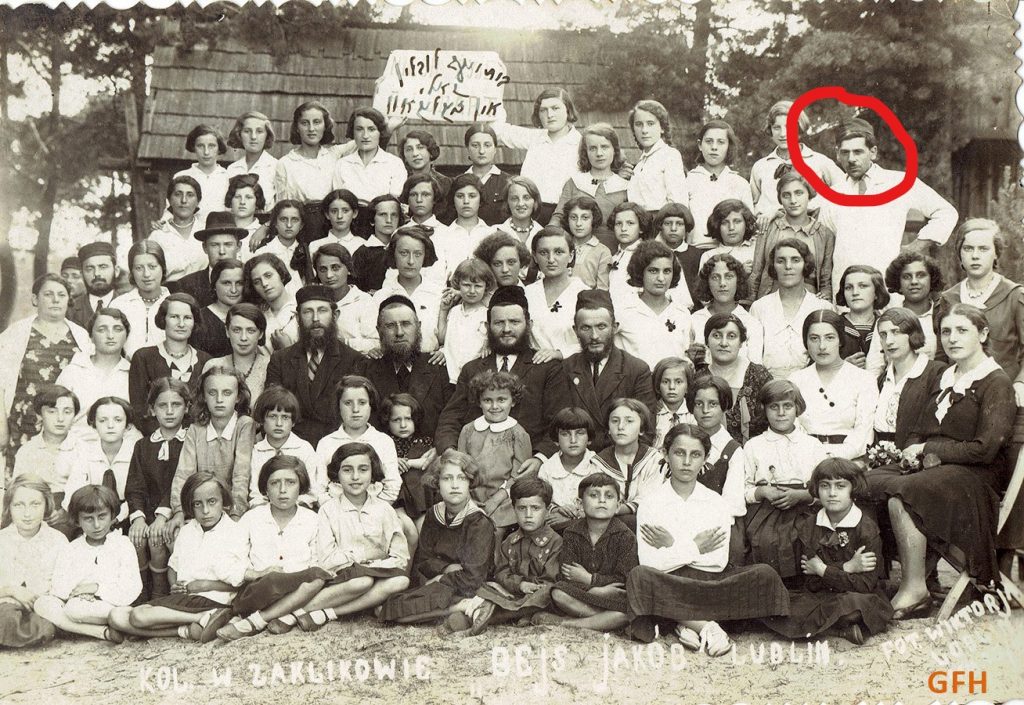

I remember the class where we read that old tale from “Yalkut Shimoni”, about the Jewish girls who were taken captive.

We were instructed to memorize it, and apparently the power of memorization is strong, because in these moments I can hear the words whisper in my brain, like ghostly distant echoes: “A tale of seventy virgins who were captured and set on a ship to be set in crates and they said to each other: let us sanctify the name of God and not be desecrated by goyim…”

In that classroom, while Hindy was reading the tale, her voice trembled.

“Miss Hindy, and what did the virgins do?” my voice also slightly trembled, although I didn’t dare utter the real question I wanted to ask. I didn’t dare ask what exactly the goyim planned to do to the virgins, what horrifying desecration they were escaping from, how this desecration was acted out… how is it that… but the right answer always fluttered in me. Not one of us doesn’t know the right answer.

“They all sanctified the name of God and jumped off the ship”, Hindy answers, her eyes avoiding mine.

“Good for them!” Ruthke, sitting next to me, cannot hold back “Really, good for them!”.

Even I smile with admiration. Not one of us doubted that was the only possible way, that it is impossible to conceive a more proper or respectable ending.

And indeed, the last sentence of the tale does not leave room for a doubt: “What did the virgins do? They stepped up to the deck, jumped off to the sea, and drowned themselves in the sea”.

The tale ends with this basic simple information. The text neither applauds the girls nor criticizes them. It just states the facts. Tells what is important for us to know.

Ruthke calms down.

She is bundled in the corner, humming a familiar melody to herself. One by one the girls join in, at first hesitantly, and then with greater force, “And on the Shabbos… Challahs and fish…” I look at the little faces around me, they open up and fill with hope. Rokhi and Pessi, and Shifra, and Dassi. Slowly the singing grows louder, until loud banging sounds are heard from the door.

“Quiet! Quiet now!” a sharp voice commands.

And a second deeper voice adds “Soon we will hear you singing other songs entirely”.

“Ahh” a third voice snarls, “Soon you will sing like birds to daddy hop!”. A moment of silence is followed by wild laughter.

My throat contracts.

This rasping laughter disgusts me. The body remembers and shivers. There is a vast difference between general random knowledge and clear certainty. This laughter is certain. We all start to silently whimper, the room fills up with sobbing, even Hindy and the principal’s chins start to tremble, and Pessi too. It is a weird cry, that expresses more shock than sorrow.

Knocking on the doors again. “Quiet there! No crying now! There will be plenty of time to cry later!”.

The deeper voice growls “Yes, yes, you will cry from every hole… be wet from every hole!” and again this laughter is swallowed by the sobbing that immediately renews itself.

Ruthke alone has stopped crying; she looks ahead, staring into the emptiness.

The principal, pale as snow, fastening the collar of her nightgown over and over, is beginning to look as crazy as Ruthke. Pessi clings to me, I feel her tears wet my neck, irritating my skin once again.

I do not cry, in my head the ghostly whispers of the tale rise like big black waves, “and these virgins said to each other: let us sanctify the name of God and not be desecrated by goyim… and drowned themselves in the sea.” The words burst out of me now like blue smoke, like wet foam, but no one can hear me.

And now they all cry and repeatedly say, we shall not be sold to disgrace, no, not to disgrace. “What did the virgins do? They stepped up to the upper deck, jumped off, and drowned themselves in the sea.” Again these ghostly voices rise and erupt out of nowhere. Suddenly Raisy, who was sitting in the corner until now in a sort of stiff silence, begins to mumble “A tale of seventy virgins who were captured and set on a ship…” and everyone joins her, and their voices grow louder. Holding hands, swinging back and forth and the sound of the growing whispers is filling the hall. Ninety-three white nightgowns horrifyingly repeating again and again: “What did the virgins do? They stepped onto the upper deck, jumped off, and drowned themselves in the sea.” Drowned themselves in the sea! Sank deep into the sea, death in their eyes, and their young flesh freezing with every passing moment, just so the goyim will not lay a hand on them! Not even one small finger! And again “A tale of seventy virgins who were captured and set on a ship…” and the principle’s face glows with pride and contentment, and Hindy’s face and Rukhi and everyone’s faces blush in a beautiful outburst of holiness, and my mouth mumbles with everyone those words floating in my brain, but within me screams a great wild wind, calling again and again “No, no!”.

The principal almost smiles while tears burst from her eyes, and says with a trembling voice, “How brave you are, my dear ones, you are the ones who continue the glowing chain of the girls of Israel, you are the ones who will continue the tradition of our mother Sarah”, and she will soon produce out of thin air the poisonous pills.

By now you know how the story ends, right?

You know that Hindy, or maybe the principal, or maybe just one of us, will pass the poisonous pills among us and we will happily grab them and shove them straight down our throats.

Ruthke and I will die holding hands, knowing we are doing the right thing, sanctifying God’s name.

When they find us, they will say we looked like angels, lying peacefully on the beds with tranquil faces. This is of course a lie, the facial expression of someone who swallowed poison is far from the facial expression of an angel. But that is what you will say. That is what you will want to say.

9.

The air was filled with a malign sweetness in that distant summer when Riki and I started the game.

Cats meowed and scratched under the house, fruit flies swarmed on the small kitchen’s balcony, and we played.

Our tiny six-year-old hands barely managed to drag the enormous blankets from Miriam and Avner’s bedroom. And afterward, with a growing expertise that developed from one game to the next, we would create for ourselves a soft nest on the room’s floor, lying one next to the other, and began to moan.

“Oh! We’ll never see Mommy and Daddy again…” Riki draws out the words in an attempt at dramatic flair, although I often wonder if being separated from hot-headed Mrs. Peretz who yells so much would actually be such a great loss to her.

“Never! Never ever!” I repeat insistently, wiping away an imaginary tear (and maybe memory is deceptive? Maybe a real tear sparkled there in the corner of the eye? Maybe those memories are more painful than I care to remember today?), “and we won’t see our friends…” another sigh escapes the tiny mouth, “and not the games and books… ever again.”

“But!” Riki determinedly places a dirty hand on the flat surface under which the heart lies. “We’ll forever be… good girls!”, the thin fingers clench into a fist.

This is my signal to mournfully walk to the kitchen, and return, carrying with sacred awe the blue “Emma” soap box.

“Here”, I say “Here is the poison, my little sister”, my fingers dipping into the bitter soapy paste. “Here, take some, sister”.

And Riki, her small facial features expressing total earnestness, takes the paste from my fingers, and very slowly, with the deepest intentions, puts it into her mouth. Everything is performed with extreme caution! The soap must not touch the palate, as we have learned from bitter experience.

And here, also, my soapy fingers stretch to the back of the expectant mouth.

“Ahh! Ahh!” our little bodies squirm. “Oh! Poison! Oh, who shall save me? The stomach hurts so much!” Pleasure and pain combine within us in a true mixture of emotions. We are dying, what bliss.

“And always” I gurgle. “We were good! We die as good, good girls!”

“The best… and purest… God, take us to you!” Riki, always the first to die, drops down beside me with a blissful expression, and I lie on my back immediately after her, my body tense, and my lips whisper the last words “Holy… Always… I’m yours… God.”

Many years will pass before we incorporate the soldiers into the story.