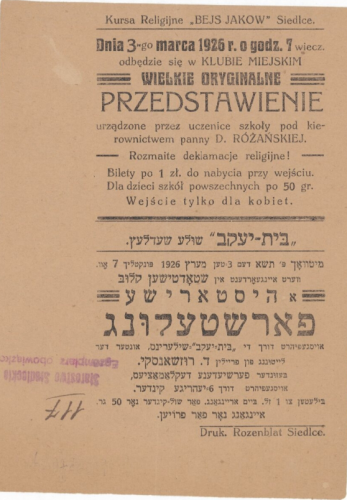

An Object:

Among the few items my parents brought with them from Europe when they emigrated to America is a Hebrew textbook my mother (Sara Seidman, née Abraham) wrote by hand, from memory, for the Bais Yaakov school she ran in the Föhrenwald Displaced Persons Camp in Germany. The textbook is written on the blank pages of a book of Gestapo order forms, for lack of other paper.

A Letter:

An August 1945 newspaper report in Sha’arim, in the form of a letter from Bergen Belsen signed by Rivka Horowitz, describes conditions in the camp after Liberation. A group of religious women, the most serious of whom were Bais Yaakov teachers and graduates of Bnos groups in Sandz, Kraków, Sanok and elsewhere, had come together to try to rebuild Jewish life.

Horowitz writes that she will not describe their ordeal of blood, except to say that they survived with their purity and beliefs intact. Rather, she begs her readers to supply her and her group with religious books, for the work they were undertaking.

“Despite the obstacles she faced, she managed to keep kosher and observe the Sabbath. Because of her dedication to her faith, Polish partisans later called her the Swieta Partizanka (saintly partisan) . . . They eventually made their way to Austria where they came to the Bad Gastein and Salzburg displaced persons’ camps. Itke worked there organizing religious schools for girls, Bnos.”

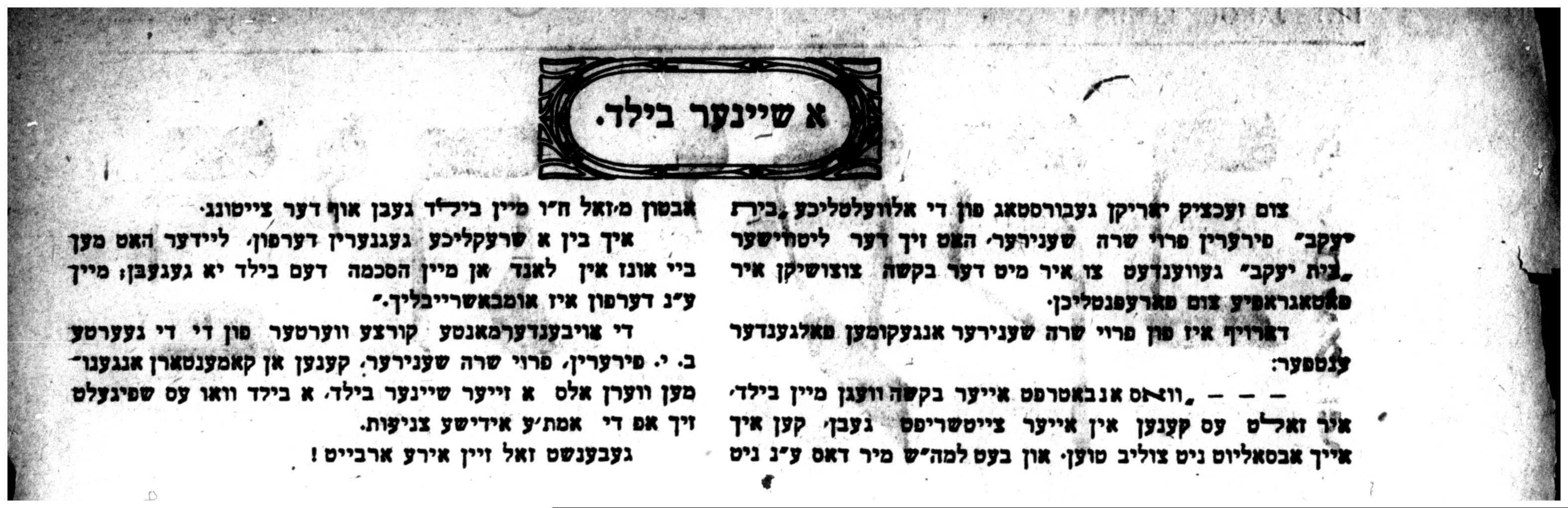

A Photo

The Holocaust Museum photo archives contain a number of photos of two extraordinarily beautiful sisters, Itka and Esther Ass.

Itka, who had studied for a time at the Kraków Seminary, escaped from the Nowogrodek ghetto in 1943 and joining a number of Jewish and non-Jewish partisan bands, including the one led by the Bielski brothers. Itka, we are told, carried a weapon, as one of the few armed women in the Bielski group.

A photo of the two sisters, reproduced with the permission of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archive on our website, shows them seated at a Sabbath table, set with candlesticks and wine, among a group of mostly young women—a child sits on a lap, and one woman appears to be middle-aged—under a sign that reads “Bais Yaakov l’khu venelkha.”

This object, photo, and letter are fragments of the least-known chapter of Bais Yaakov history: the re-emergence of Bais Yaakov among Jews fleeing from wartime threats and among the refugees and displaced persons of the immediate post-war period.

Interwar Bais Yaakov produced a host of documents, and Bais Yaakov in the two major centres—Israel and North America—of more recent history is visible enough as a contemporary phenomenon. But Bais Yaakov in the postwar context was different from either its predecessors or the movement that followed, and the intriguing traces of this culture are available only in fragmentary form.

What we do know is that the immediate aftermath of the war saw the rapid re-emergence of Bais Yaakov schools and Bnos groups, with schools and groups founded in the displaced persons camps of Bad Gastein, Eschwege, Feldafink, Föhrenwald, Frankfurt, Landsberg, and Zeilsheim. Bergen-Belsen had two Bais Yaakov schools and even a rudimentary teachers’ seminary.

By 1951, there were 150 Bais Yaakov schools and Ohel Sarah kibbutzim in Germany, Austria, Italy, Sweden, France, and (until Soviet regimes shut them down), Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Poland.

A Bais Yaakov that had served the refugee community in Shanghai continued for a time after the war. A photo of that school shows that the British detention camp in Cyprus, which held Holocaust survivors attempting to immigrate illegally to Palestine, had both a Bais Yaakov school and a few Bnos chapters.

In some camps, Bais Yaakov girls banded together to look for hidden Jewish children, founding orphanages where these children could be brought back to religious observance.

As my mother’s textbooks attests, the cultural practices of Bais Yaakov in the DP camps were necessarily distinct from those founded in the interwar period, or in the post-Holocaust Israel and North America. Bais Yaakov schools and Bnos chapters served a refugee community struggling to rebuild itself with limited resources, with teachers and students who had been orphaned, traumatized, and imprisoned.

For many in the DP camps, it was not all clear where they should rebuild their lives, or how—with many survivors drifting away from religious observance and into other ideological camps. and positions. At least some modesty norms seem to have been loosened within Bais Yaakov, if the photo from Shanghai is evidence.

The re-emergence of Bais Yaakov was aided by the network of connections forged in the interwar movement, but these schools constituted new assemblages, without the old lines of authority or institutional frameworks, without a clear road to the future. In these conditions, improvisation and memory sometimes took the place of established norms, producing, among other artefacts, a handwritten Hebrew text in a repurposed Gestapo order form.

What was Bais Yaakov at this extraordinary moment of displacement, trauma, and rebirth? What might a close reading of Rivka Horowitz’s letter, the Ass sisters’ photo, my mother’s Hebrew textbook, tell us about what Bais Yaakov was in those years, in those places?

In the coming weeks, we will publish a translation of Rivka Horowitz’s letter.

Naomi Seidman is the Chancellor Jackman Professor of the Arts in the Department for the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto and a 2016 Guggenheim Fellow; her 2019 book, Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition, explores the history of the movement in the interwar period.

There were also places like

There were also places like