There’s something a little ambivalent and paradoxical about the process of seeing a book you’ve worked on for years finally appear in print. It’s certainly gratifying to finish a book and watch it take its first steps in the (largely indifferent) world.

But the moment a book comes out is also the moment it comes to an end for you. Whatever drove you during those long years of megalomaniacal obsession, of excruciating attention to footnotes and copyeditor comments has been laid to rest.

The book, if you’re exceedingly lucky, might attract interest, controversy, reviews, a promotion.

But for you, the writer, the book is essentially dead. People who approach you with new information, who dispute your insights or congratulate you, are too late to do the book any good.

Whatever readers might feel, for you it’s on to the next thing.

I’ve experienced this not entirely unpleasant feeling with each of the three books I’ve written—a withdrawal of libidinal, intellectual interest in the topic of the book (however invested I remained in the book’s career and Amazon ranking) at the very moment of publication.

Good luck, baby, you’re on your own!

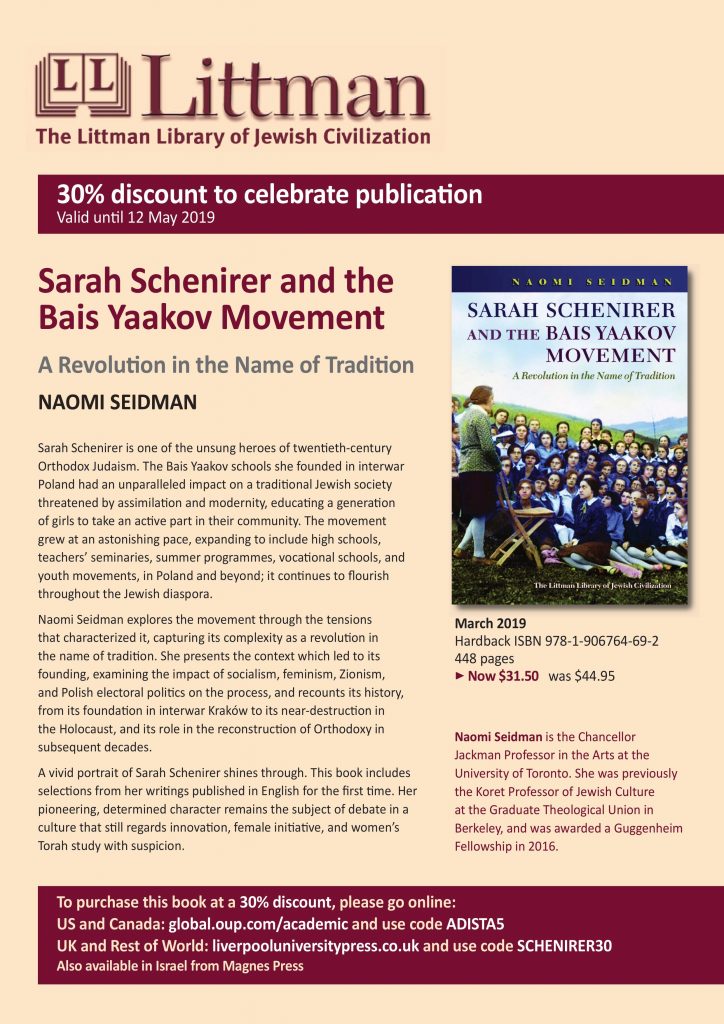

But something very different is happening with my fourth book, Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition.

Far from having moved on, my obsession with this topic is only continuing to grow, with no end in sight. The book has been out for a month or two, but rather than enjoying a break from imagining that there is no more important thing to think about than the history of Orthodox girls’ education, rather than turning my attention to the next obsession in line, here I am, busier than ever with Bais Yaakov.

The book somehow morphed a few months ago into something we’re calling, a little grandly, “The Bais Yaakov Project.” And it’s no longer mine alone.

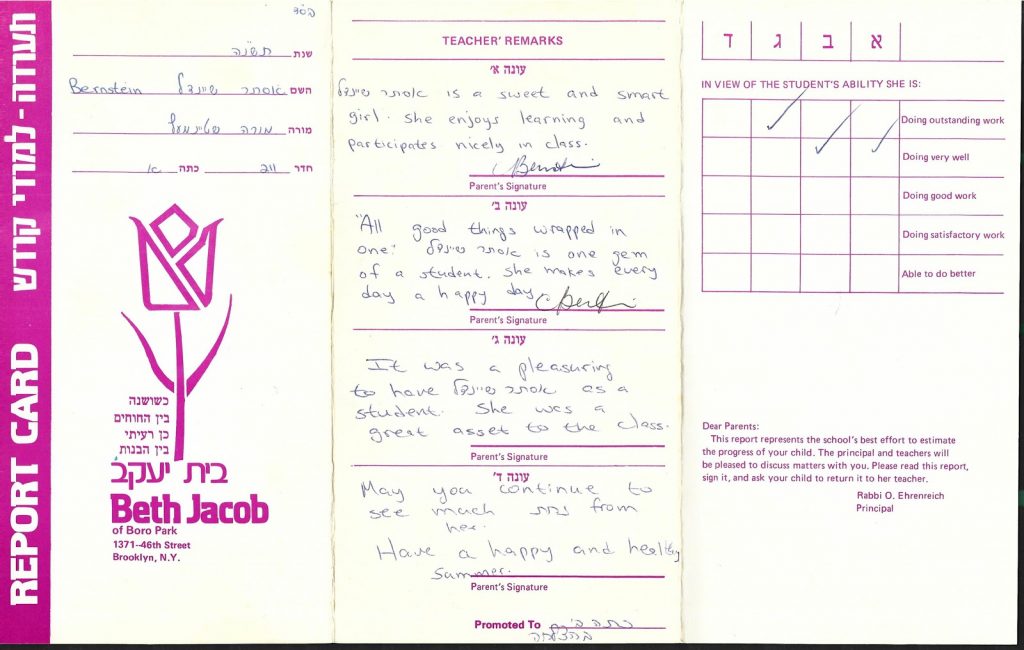

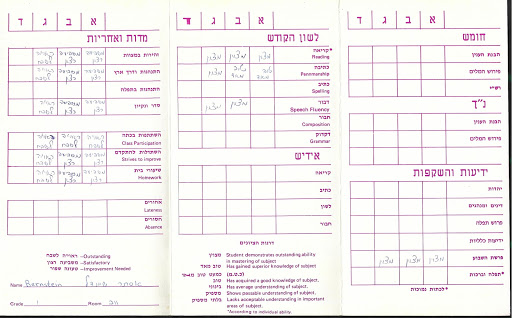

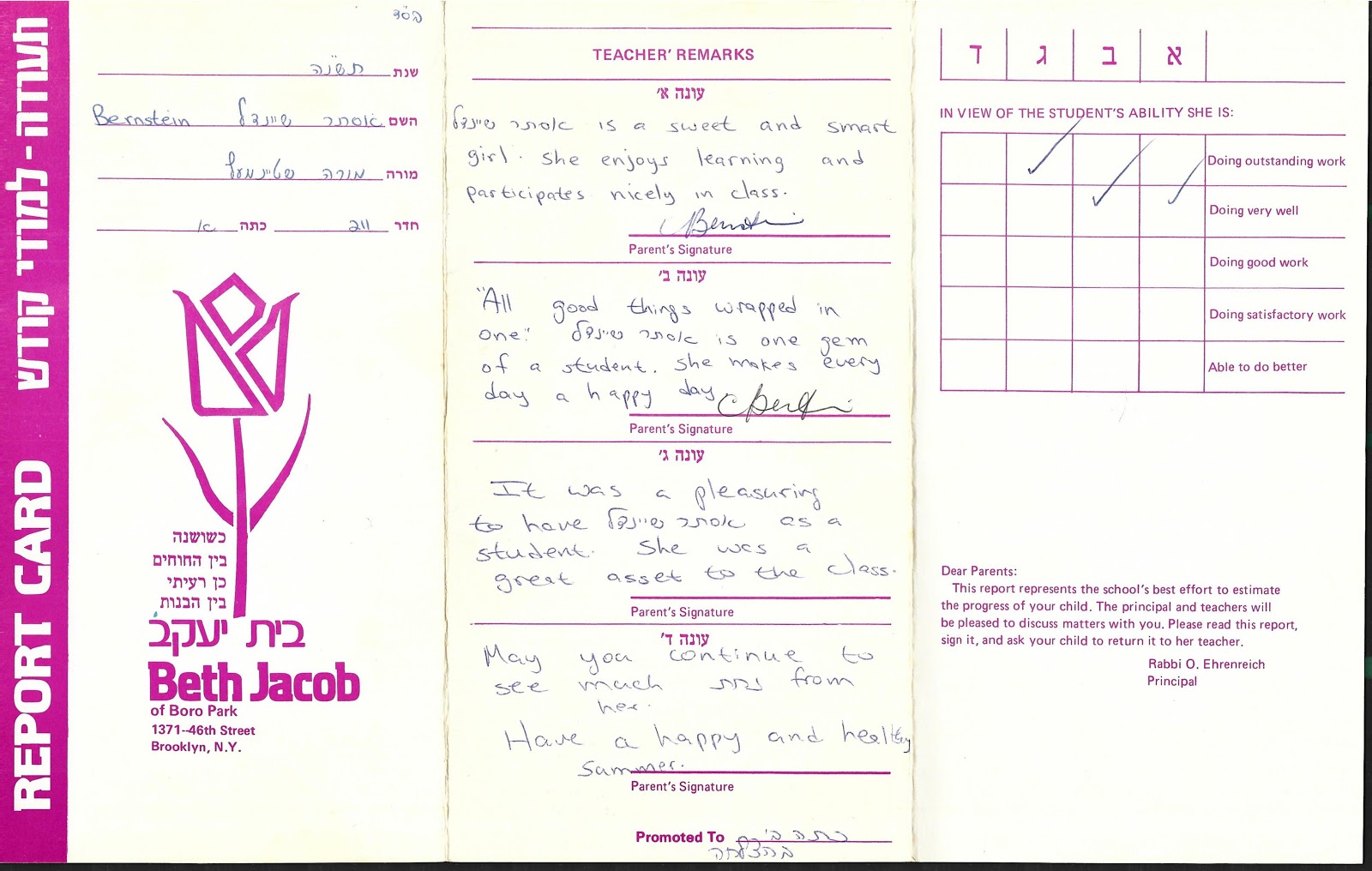

What it is: A website, beautifully designed and maintained by Dainy Bernstein, where we continue to post documents, photos, publications, blogs, videos—anything related to Bais Yaakov.

“The Bais Yaakov Project” also has a musical component, revolving around a 1931 songbook I found years ago in the archives, now coming alive in the cool arrangements of Basya Schechter. In two weeks, Basya and I will spend five days in Boulder, Colorado, at a workshop called “Archive Transformed,” which brings together scholars and artists to produce public programs.

“The Bais Yaakov Project” has taken an even more ambitious turn. Next month, the filmmaker Pearl Gluck and I are spending a few days together brainstorming how to turn this material into a documentary film, and how to fund such a film.

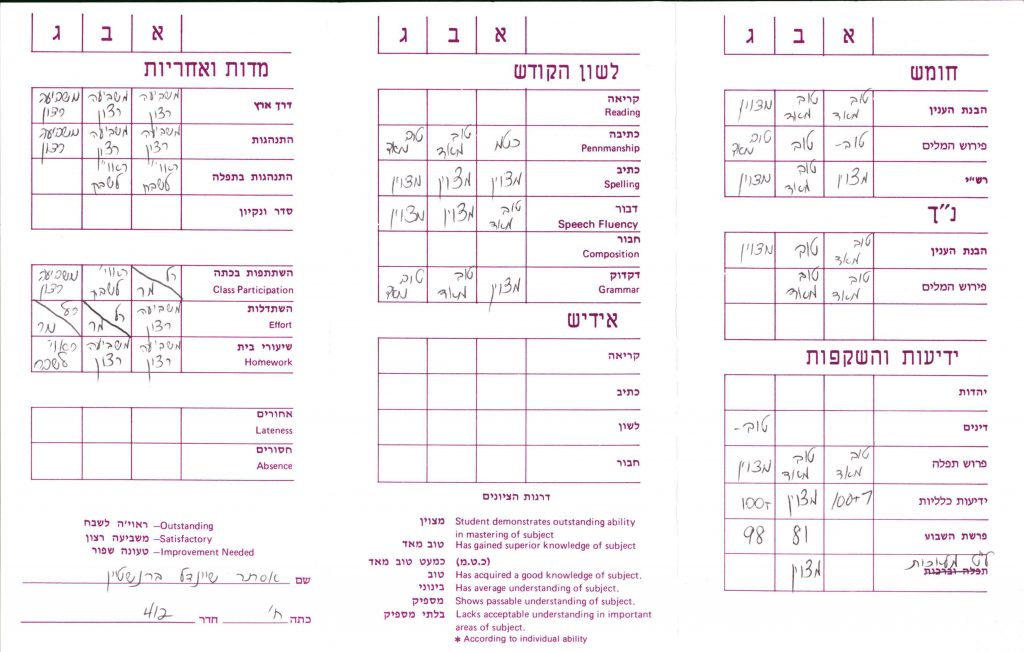

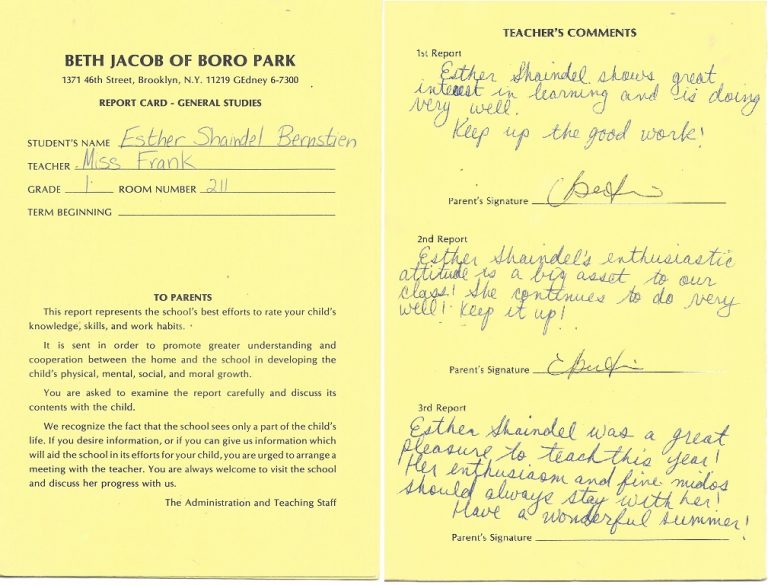

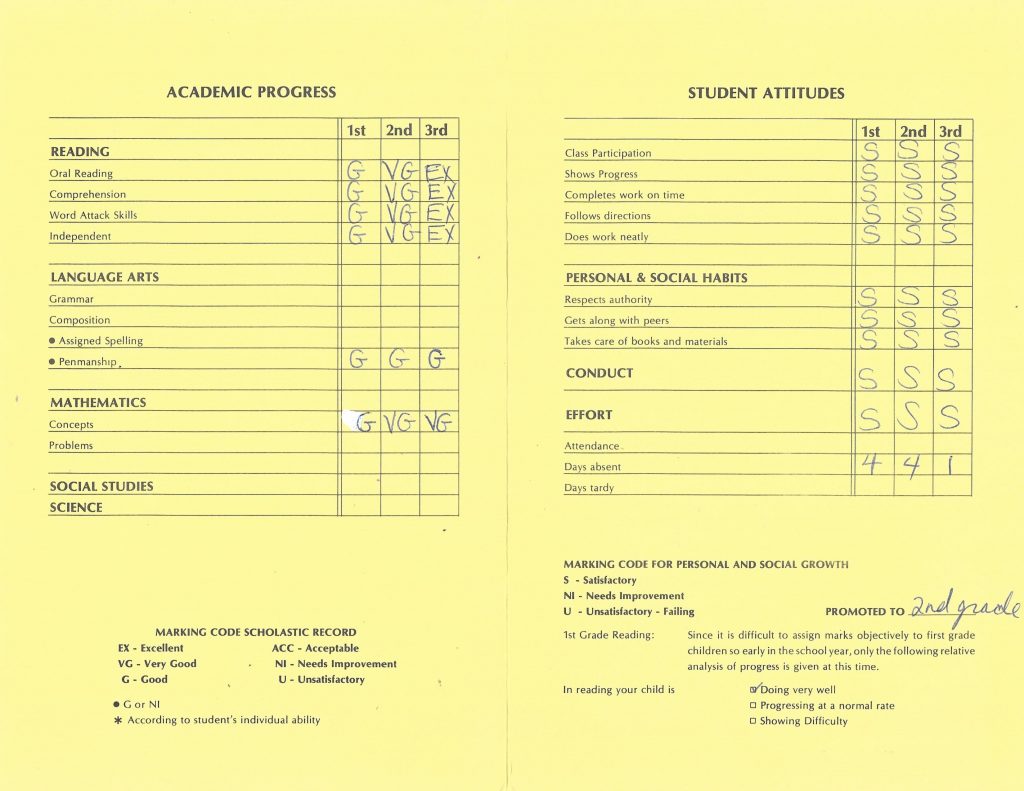

This passion that I thought was my own private obsession, it turns out, has greater reach. All of us—Dainy, Basya, Pearl and I—spent time at Bais Yaakov (more specifically, Bais Yaakov of Boro Park).

All of us went on to other things, but never, it turns out, entirely left Bais Yaakov behind.

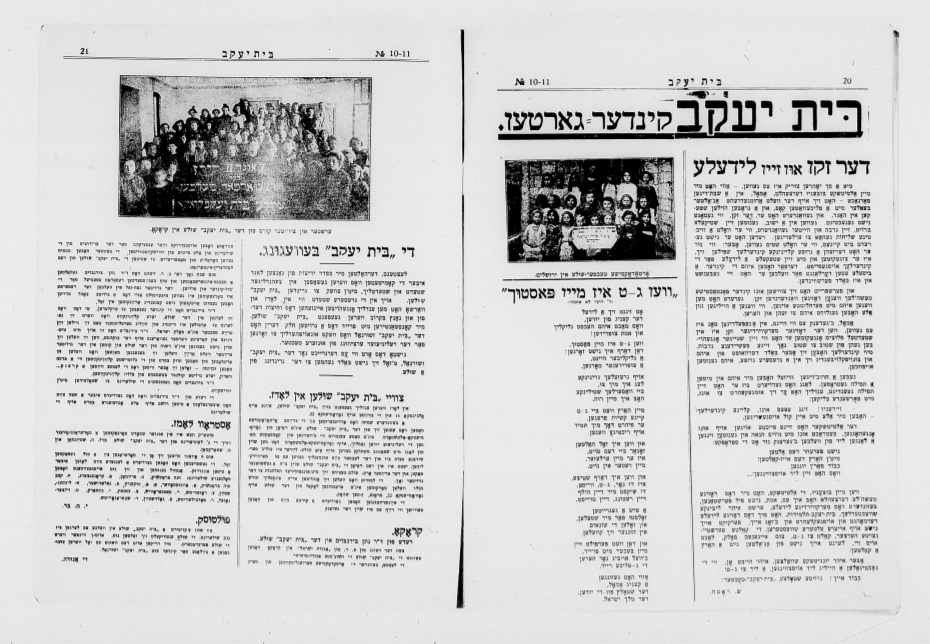

The years I spent reading old microfiche copies of the Bais Yaakov Journal were interesting (okay, also often not so interesting).

But they were nothing compared to what I felt in March, rehearsing for the concert of interwar songs of Bais Yaakov along with a group of other ex-Bais Yaakov girls, at the book launch at the Center for Jewish History. Some of the songs we sang were probably being sung for the first time in fifty or seventy years. What happened during that rehearsal was deep, and I want some more of whatever it was.

Rehearsal for the March 24, 2019, event at YIVO. Video: John Schott.

So why is this book not over, just at the point that the other books were done?

What accounts for this different trajectory, this powerful afterlife?

Part of it is that, unlike my other projects, Bais Yaakov is such a real and continuing part of the world today. A history of the movement matters to a lot more people than other things I’ve written about.

What Bais Yaakov was and is remains an open, unsettled, and controversial question. Bais Yaakov treasures its own history, but also works to (partially) obscure those aspects of its history that don’t jibe with present ideological impulses and its present realities (sleeves, for instance, are photoshopped onto old photos to make them conform to present modesty standards, as Leslie Ginsparg Klein highlights). This is rich and charged territory to be barging into, and I’m hopeful and curious about the effects of my work for more than just the usual reasons of scholarly narcissism.

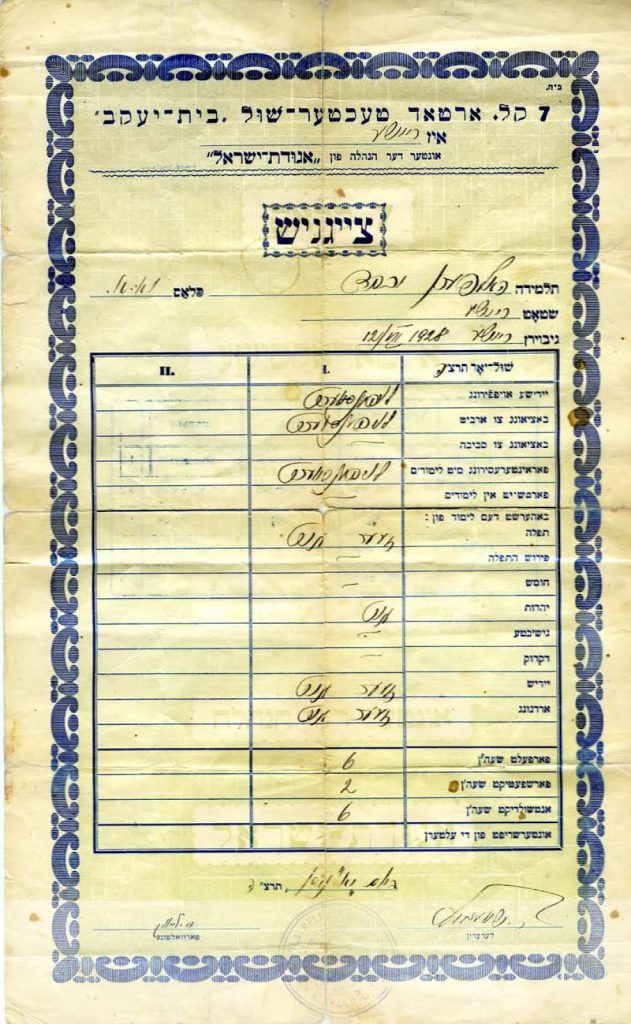

There is also another reason that this research project continues to be alive to me. The history of Bais Yaakov, it turns out, resides at least as much in private memory as it does in the library and archive, and it was only by writing the book that those private resources have become available to me. The illustrations in my book come from various archives, but since knowledge of the book has begun to circulate, I have suddenly found myself with far more material than I had while I was writing it.

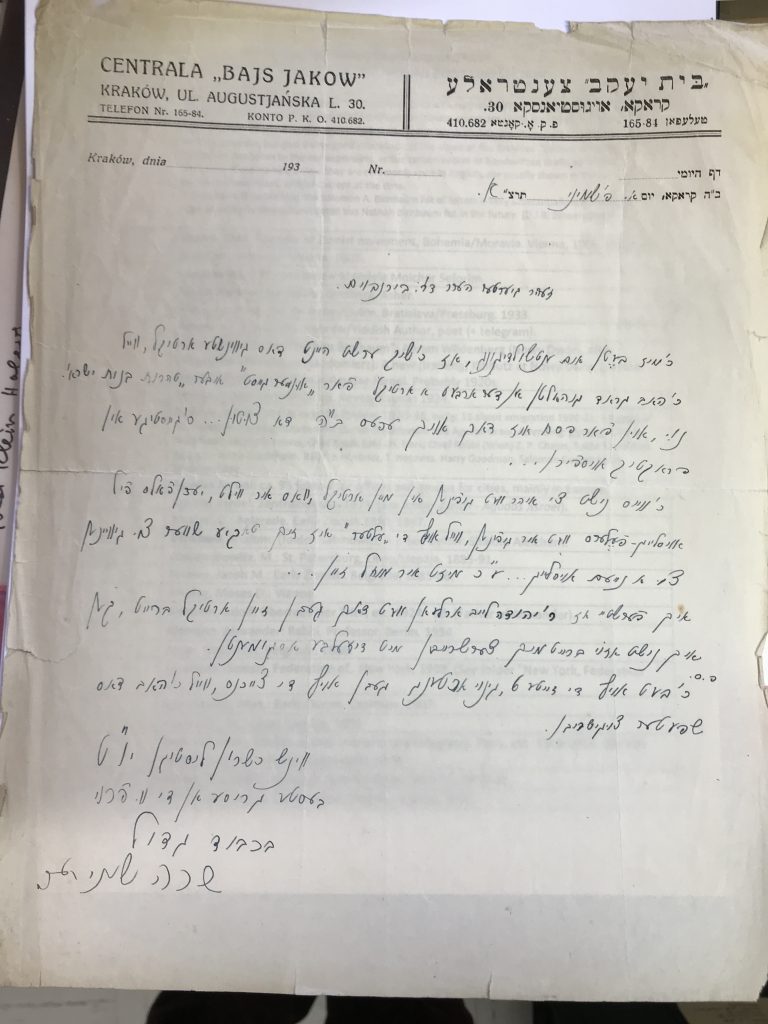

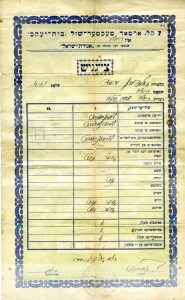

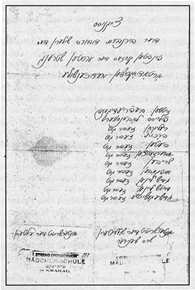

The most extensive and richest of these resources is the private collection of Devorah Epelgrad Cohn. Her grandson Naftali Cohn, a professor at Concordia University, contacted me after seeing a posting for a book talk I was giving at the university. We have only begun to post the photos, speeches, and videos he gave us access to, which provide glimpses of a world I was otherwise unable to find in the archives:

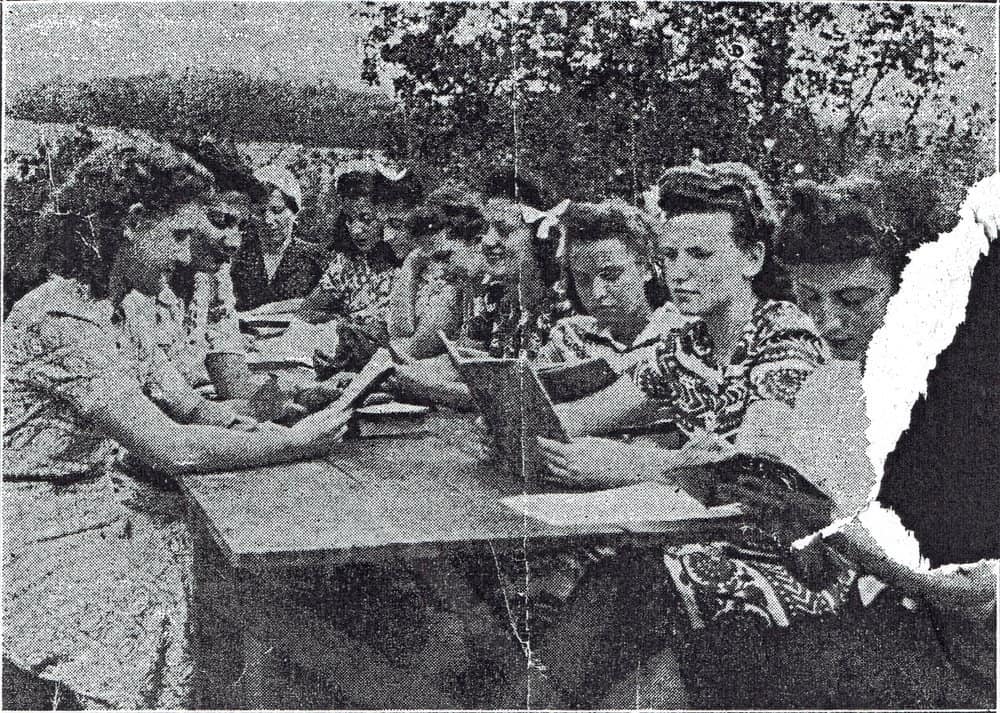

- a lovely photo of seminary girls lounging on the grassy strip between the Krakow Teachers’ Seminary and the Vistula River that flowed beside it,

- a Seminary diploma from 1934,

- a photo of seminary girls on vacation in a cart AND the destination of that cart-ride—a beautiful lake high in the Tatar mountain range,

- a beautiful shot of the interior of the sixth-grade classroom of the Bais Yaakov of Slonim,

- a photo of a class play called “Cantonists,”

- and many others.

And if that were not enough, Devorah Cohn carefully labeled these precious artifacts, wrote about her recollections of the events they recorded, and has been videotaped discussing these photos.

Any one of these photos would have made it into the book, and I would have loved to have the one of the girls in the mountains as the cover photo. It’s too late for the book, but the website continues to grow, and along with it my fascination with Bais Yaakov.

The history and ongoing life of Bais Yaakov is a collective story to tell, and the story I have told is only one among many others.

My perspective is not less legitimate because it has been shaped by my leaving the Orthodox world, but certainly my book cannot remain the only serious academic monograph on Bais Yaakov. Important work is being done by Polish historians (many of them feminists), work that is almost entirely unknown in North America.

A number of excellent theses and dissertations by Orthodox historians surely deserve more attention.

It’s a sign of the richness and importance of the history of Bais Yaakov that it has attracted interest in such disparate quarters, far beyond the academic conferences that I thought were the limits of my scholarly reach. With the publication of my book, I have a front-row seat on a busy intersection of the present and the past, Bais Yaakov girls and radical feminist songwriters and filmmakers, Orthodoxy and academic scholarship, Poland and North America and Israel. Whatever happens, I’m not ready to quit this arena.

The work—our work—is only beginning.

Naomi Seidman is the Chancellor Jackman Professor of the Arts in the Department for the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto and a 2016 Guggenheim Fellow; her 2019 book, Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition, explores the history of the movement in the interwar period.