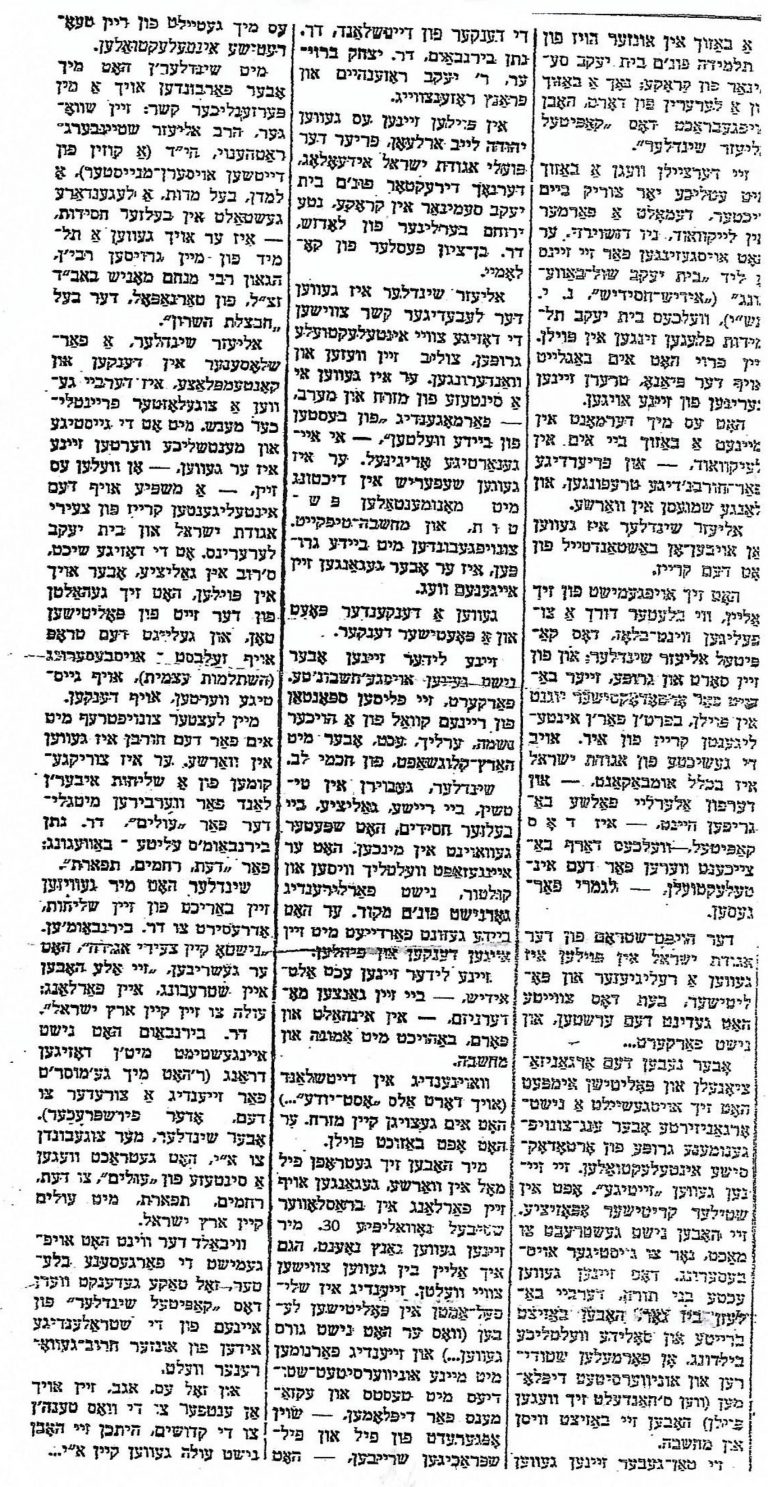

In September 1975, my father, Hillel Seidman, wrote an article in the Algemeiner Journal called “Pages from ‘the Eliezer Schindler Affair.’”

It starts:

A visit to our house by a student of the Bais Yaakov Seminary in Krakow; another visit by a teacher from there brought back to mind the whole Eliezer Schindler affair. The two women tell the story of visiting the poet, who was then a farmer in Lakewood, New Jersey. He sang for them his Bais Yaakov song, which Bais Yaakov girls in Poland used to sing. His wife accompanied him on the piano, tears streaming down both their faces.

That reminded me of my own visit to Lakewood, and earlier times we met before the Holocaust times, talking for hours in Warsaw.

The song Schindler sang is the first one in the Bais Yaakov songbook I found so many years ago in the YIVO archive, the catchiest one, and the only one that is still sometimes remembered. Dainy Bernstein supplied a chorus, absent from the songbook, that they had heard in their family.

Recording by Dainy Bernstein supplying the chorus missing from the songbook [with an incorrect word in the verse]:

I had long seen and noticed that the song was written by Eliezer Schindler, and known, too, that he had been a farmer in New Jersey. But I had not heard the story that my father relates here, that Schindler and his wife sang the song for a visiting teacher and graduate of the Krakow Seminary, and cried.

This I learned from the article, which Miriam Oles, Schindler’s granddaughter, emailed to me this week, with the question of whether Hillel Seidman was a relation.

Beyond the moving picture of the song, the detail that catches me is the Lakewood farm. Why a farm? And why in Lakewood?

My father doesn’t exactly say why Schindler chose to live outside the centers of Orthodox life in America at the time, but he does paint a picture that helps us guess at an explanation. Schindler, the poet and farmer, was a living bridge between Germany and Poland, combining an artist’s life and deep connections to his Hasidic past.

Schindler traveled to Poland to recruit Agudah youth to Nathan Birnbaum’s utopian project, Olim (The Ascenders), which called for Jews to return to working the land, to live simply and collectively, and to devote themselves to spiritual pursuits. The men differed, my father says, on whether this new way of life should establish itself in the Land of Israel or rather transform life in the diaspora. Schindler seems to have fulfilled the agricultural part of this vision, without, as far as I can tell, the collective around him that Olim envisioned.

Was Olim a failure? Was Schindler its last or only member?

Schindler was always a rare bird, but in Europe he was also part of the Agudah. Writing in 1975, when an Orthodox Jewish poet was harder to find, my father felt the need to explain to his Orthodox readers that Agudath Israel in Poland was not just—as they assumed—a political organization, guided by a group of religious authorities. Alongside this organization was a tightly connected non-organization of intellectuals, writers, and dreamers.

My father writes about these intellectuals:

They were permanently marginal. Often in silently critical opposition. They had no desire for power, only for spiritual development. They were truly devoted to the Torah, but at the same time they had a solid and comprehensive secular education. Without formal studies or a university degree (at least in Poland), they possessed both knowledge and thought.

Agudah continued – and continues now – as a political organization answering to the rabbinical authorities, to Da’as Torah. But where were and are the marginal counterparts that also formed part of the interwar Agudah world, the intellectuals and poets and dreamers? Did Schindler live on a farm “in silently critical opposition” to the yeshiva nearby?

It was no surprise that the intellectuals my father described, who inhabited the margins of the Agudah, are also the ones most likely to show up in the history of Bais Yaakov.

Did Schindler write a love song to Bais Yaakov because he identified with the marginality of girls and women in a world dominated by rabbis and activists? Did Bais Yaakov represent a more open field for cultural experimentation than was available in the male sphere?

My father says that Schindler was particularly beloved as a poet in Bais Yaakov. Whatever was going on at the yeshiva, somewhere out of town Bais Yaakov girls were making pilgrimages to the poet and farmer, to hear him sing the song he had written for them.

Naomi Seidman is the Chancellor Jackman Professor of the Arts in the Department for the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto and a 2016 Guggenheim Fellow; her 2019 book, Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition, explores the history of the movement in the interwar period.

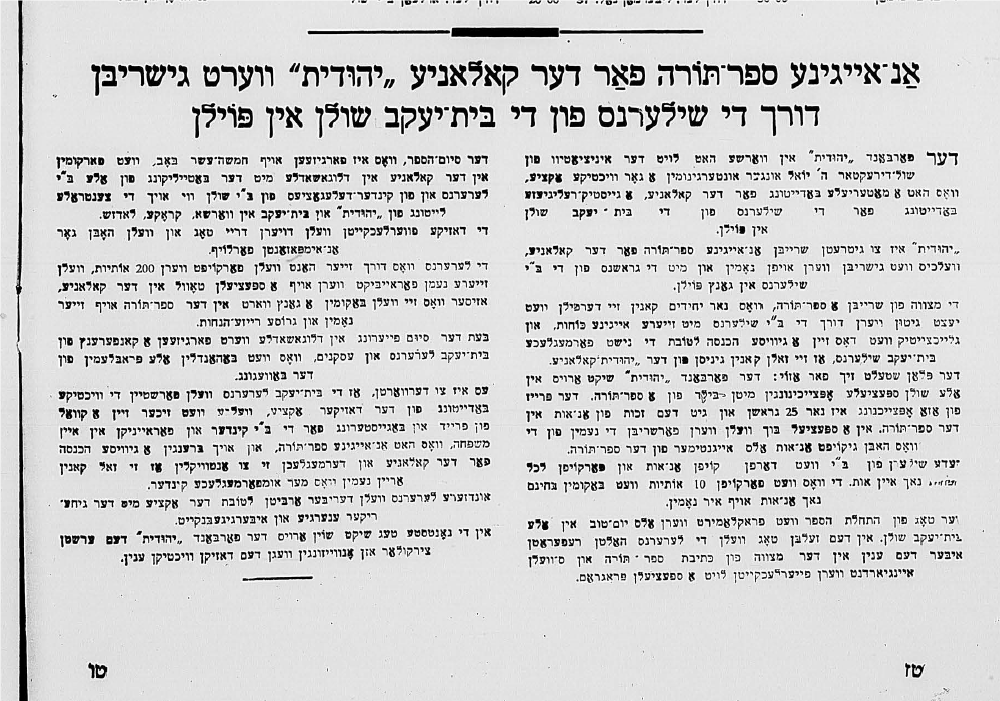

The article goes on to describe the efforts to raise funds for the Sefer Torah and for scholarships to the camp throughout Poland, with girls buying letters and schools taking the opportunity to teach the laws of the Torah scribe, and the mechanisms of inscribing a Torah. Teachers who raised funds for 200 letters would have their names inscribed on a special plaque in the camp. The installation of the Torah scroll, the report continues, took place beginning on Tu Be’Av in the camp, with festivities, a conference, and other programs going on for three days. As it concludes, the act of collectively inscribing a Bais Yaakov Sefer Torah would certainly create a groundswell of joy and enthusiasm for Bais Yaakov girls, “uniting them in one family, which has one Sefer Torah.”

The article goes on to describe the efforts to raise funds for the Sefer Torah and for scholarships to the camp throughout Poland, with girls buying letters and schools taking the opportunity to teach the laws of the Torah scribe, and the mechanisms of inscribing a Torah. Teachers who raised funds for 200 letters would have their names inscribed on a special plaque in the camp. The installation of the Torah scroll, the report continues, took place beginning on Tu Be’Av in the camp, with festivities, a conference, and other programs going on for three days. As it concludes, the act of collectively inscribing a Bais Yaakov Sefer Torah would certainly create a groundswell of joy and enthusiasm for Bais Yaakov girls, “uniting them in one family, which has one Sefer Torah.”